Neoplasmic

tumors are areas of localized tissue growth where cellular

proliferation occurs without the oversight of the bodies growth

control mechanisms. These are split into two categories, malign

growths which are often fatal, and which are the second highest cause

of death among modern human populations (after coronary disease), and

benign growths, which are not typically lethal but which often cause

chronic long-term illnesses. Cancers are often considered to be

modern diseases, caused by poor lifestyles choices which make us more

prone to the genetic damage that causes them, but they are known in

both the fossil and archaeological record, albeit at extremely low

levels, and probably occurred at higher levels than we are aware of,

as only cancers affecting hard tissues such as bone are likely to be

preserved.

In a

paper published in the South African Journal of Science on 28 July

2016, Patrick Randolph-Quinney of the School of Anatomical Sciences

and Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of theWitwatersrand, describe a benign tumour from a 1.98-million-year-old

Australopithicine from Malapa Cave at the Cradle of Humankind WorldHeritage Site in Guateng Province, South Africa.

The

tumour is located in the sixth thoracic vertebra of an individual

known as MH1 (Malapa Hominin 1), a juvenile male with a development

roughly equivalent of a 12-13-year-old Modern Human, which is the

specimen from which the species Australopithecus sediba (thought

to bebe a likely candidate for the species ancestral to the genus

Homo) was described. This

specimen is one of two specimens of Australopithecus

sediba from Malapa Cave, which,

along with a number of other Hominins, are thought to have fallen

into the vertical cave and died, rather than used it as a dwelling,

as with the other caves at the Cradle of Humankind site.

The tumour measures approximately 6.7 by 5.9 mm and penetrates the

bone from the right surface of the bone. The right portion of the

vertebrae appears thickened relative to the left, apparently

indicating remodelling of the bone in reaction to the tumour. The

lesson formed by the tumour widens beneath the entrance hole, then

narrows deeper into the bone, deviating slightly to the right. It

does not penetrate the vertebral canal, but the position of and bone

modification caused by the tumour may have affected the articulation

of both the spine and the right shoulder, and could quite possibly

have been a source of acute or chronic pain and even muscle spasming.

Sixth thoracic vertebra of juvenile Australopithecus sediba

(Malapa Hominin 1). Partially transparent image volume with the

segmented boundaries of the lesion rendered solid pink. Volume data

derived from phase-contrast X-ray synchrotron microtomography. (a)

Left lateral view, (b) superior view, (c) right lateral view. Paul

Tafforeau in Randolph-Quinney et al. (2016).

Given the thickening of the bone around the lesson, Randolph-Quinney

et al. rule out the possibility of this being a post-mortem

artefact. The absence of inflammation around the the tumour is also

indicative; as such inflammation would be expected with cancers such

as brucellosis, nonspecific osteitis, haematogenous osteomyelitis or

treponemal osteitis, and the morphology of the tumour is inconsistent

with a diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis. There is no sign of the

deformation and regrowth that might be associated with a trauma such

as a healed fracture, and the youth of the victim makes it highly

unlikely that the lesson was caused by osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma

or Ewing’s sarcoma.

The possible causes of the lesson are therefore thought to be osteoid

osteoma, osteoblastoma, giant cell tumour and aneurysmal bone cyst,

of which an osteoid osteoma or osteoblastoma are thought to be the

most likely. Of these the pathology most resembles an osteoid

osteoma, though these are rare in the bones of the spine, being most

common in the lower limb bones. Randolph-Quinney et al. therefore

conclude that an osteoid osteoma os the most likely cause of the

observed pathology, but that an osteoblastoma cannot be ruled out.

See also...

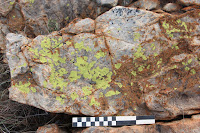

Evidence of Lichen growth on the bones of Homo naledi. In 2013 scientists in South Africa described the discovery of a

remarkable new Hominin species in the Dinaledi Cave System in Gauteng

State, South Africa (part of the Maropeng Cradle of Humankind...

Evidence of Lichen growth on the bones of Homo naledi. In 2013 scientists in South Africa described the discovery of a

remarkable new Hominin species in the Dinaledi Cave System in Gauteng

State, South Africa (part of the Maropeng Cradle of Humankind... Malignant Osteosarcoma in a 1.7 million-year-old Hominin Metatarsal from Swartkrans Cave, South Africa. Malignant

Cancers are the biggest singe killer of...

Malignant Osteosarcoma in a 1.7 million-year-old Hominin Metatarsal from Swartkrans Cave, South Africa. Malignant

Cancers are the biggest singe killer of... Hominin rib from Sterkfontein Caves. Sterkfontein Caves is a palaeoarchaological excavation site about 40 km

to the northwest of Johannesburg in Gauteng State, South Africa, which

forms part of the Maropeng Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site

has previously produced a large volume of early Hominin material

(fossils of...

Hominin rib from Sterkfontein Caves. Sterkfontein Caves is a palaeoarchaological excavation site about 40 km

to the northwest of Johannesburg in Gauteng State, South Africa, which

forms part of the Maropeng Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site

has previously produced a large volume of early Hominin material

(fossils of...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.