Emperor Penguins, Aptenodytes forsteri, are the largest species of Penguin, and have become iconic symbols of Antarctic wildlife, being the only Vertebrates that overwinter on the Antarctic continent. The species is dependent on the presence of anchored sea ice (sea ice attached to land rather than drifting) during the breeding season, with breeding and moulting taking place on the ice, while foraging for food is largely accomplished in waters around the ice shelf. Emperor Penguins typically arrive at their breeding grounds in March and April and lay eggs in May and June, with chicks hatching in July and August and fledging in December and January. This means that stable, land-fast ice needs to remain in place between April and January for breeding to succeed.

This means the Emperor Penguins are directly threatened by climate change, with loss of sea ice, or changes in its distribution, known to have caused failure at individual breeding sites in the past. Attempts at predicting the future of the species have painted a bleak picture, with current climate predictions suggesting that 90% of Emperor Penguin colonies will no longer be viable by the end of the twenty first century due to global warming and the accompanying loss of sea ice. This is the first anthropogenic threat the species has faced; Emperor Penguins have never been hunted, never suffered direct habitat loss due to Human expansion, and their fishing grounds have not been overfished by Human competitors, making them the only known Vertebrate species for which climate change is the sole threat to their long-term survival.

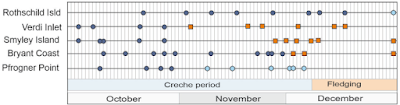

There are five known Emperor Penguin colonies on the Bellingshausen Sea, at (from east to west) Rothschild Island, Verdi Inlet, Smyley Island, Bryant Peninsula and Pfrogner Point. All of these colonies have been discovered within the past 14 years, using medium resolution satellite imagery, and subsequently had their populations assessed using very high-resolution imagery. Only the Rothschild Island colony has ever been visited, although the Smyley Island colony has been sighted from the air. The sites are assumed to be breeding colonies because they are occupied between October and December, when large aggregations of non-breeding Emperor Penguins have never been recorded. The largest of the Bellingshausen Sea colonies is on Smyley Island, where an average of 3500 pairs have been recorded, while the smallest is on Rothschild Island, with only 630 pairs recorded.

In a paper published in the journal Communications Earth and Environment on 24 August 2023, Peter Fretwell of the British Antarctic Survey, Aude Boutet, an independent researcher from Paris, and Norman Ratcliffe, also from the British Antarctic Survey, discuss the impact that loss of sea ice across much of the Bellingshausen Sea in November and December 2022 had upon Emperor Penguin breeding colonies of the area.

Four of the five Penguin colonies were affected by early sea-ice loss in November 2022; at this time much of the Southern Ocean around Antarctica was affected by sea-ice loss, but the Bellingshausen Sea suffered the most significant loss. Three of these colonies had been visible in satellite images in late October and early November, but were abandoned by the start of December, when the chicks should have begun fledging. The Pfrogner Point colony, which is the most westerly on the Bellingshausen Sea, and which was outside the area of the sea-ice anomaly, was also abandoned at some point between 29 October and 9 November 2022, probably due to earlier loss of sea ice.

Exact timings of chick hatching and fledging on the Bellingshausen Sea have never been made, so assumptions about when these events occur have been based upon observations on Cape Washington and Pointe Géologie in the east Antarctic, where fledging begins in early- to mid-December, and finishes in late December or early January. This makes it likely that the Bellingshausen Sea colonies suffered total failure in 2022, due to losing their sea-ice before these dates. It is possible that some chicks were able to survive on grounded icebergs, but this is unlikely to have been a significant proportion of the whole, and the three colonies which disappeared before the onset of December were simply abandoned by the adult Penguins.

Emperor penguin colonies in the central and eastern

Bellingshausen Sea. The locations of the five emperor penguin colonies in

this region superimposed over the regional sea ice concentration anomaly

for November 2022 shown in red. Fretwell et al. (2023).

Emperor penguin colonies in the central and eastern

Bellingshausen Sea. The locations of the five emperor penguin colonies in

this region superimposed over the regional sea ice concentration anomaly

for November 2022 shown in red. Fretwell et al. (2023).Although satellite data is only available for the entire of the Bellingshausen Sea from 2018 onwards, only one of the colonies is known to have previously suffered a complete loss of sea-ice (Bryant Peninsula in 2010), and statistical models which predicted the colony failures in 2022 from satellite data suggest that it is unlikely that other such losses have gone undetected.

The Verdi Inlet colony was first detected in 2018, and has been found in satellite imagery each year since. in 2018-2021 sea-ice around the inlet did not break up until January, with an estimated 3000 pairs of Penguins using the site in November 2021. The colony was observed in September 2022, but was much smaller than in previous years. The last of the land-bound sea-ice around Verdi Inlet broke up between 31 October and 4 November 2022, with all ice having vanished by early December. No signs of Penguin activity were detected after the initial break-up of the ice, suggesting the colony was abandoned at this point.

The Smyley Island colony was first detected in Landsat imagery in 2009, and the colony has been monitored in Very High-Resolution satellite imagery by the British Antarctic Survey since that time. The colony was home to between 1000 and 6500 pairs of breeding Penguins each year, with a ten-year average of 3000 pairs. Bound sea-ice was observed around the island until at least early December, until 2022, when the ice broke up in mid-November. Prior to this, the colony had split into two groups about 4 km apart (suggesting the Penguins were aware there was a problem, and had reacted to it), Some Penguins were detected on a grounded iceberg in December, although it is unclear if any chicks survived.

The Bryant Coast colony was first detected in Landsat data in 2014, and subsequently found in images dating back as far as 2000. The colony was absent in 2010, and reached a maximum size of 2000 breeding pairs in 2014. Multi-year bound-ice was present at the colony site from 2010 until 2021, providing the Penguins with a stable year-round platform. In 2022 the colony was detected in mid-November, but again seemed smaller than usual. By 25 November, the sea-ice could be seen retreating close to the colony, and by 29 November the bound sea-ice around the colony had gone, although floating pack-ice was still present, with some brown staining (indicative of the presence of Penguins) observed on this ice. However, by 2 December all signs of Penguin activity had vanished, and the colony is presumed to have failed.

The Pfrogner Point colony was first detected in satellite imagery in 2019, and has been found in satellite images from 2018-2022, with a single estimate putting the population at 1200 pairs of Penguins. The colony is situated on an ice shelf (part of a glacier flowing out over the sea) rather than directly on the sea-ice, and appears to have shifted between the main shelf and a tongue of ice associated with an outflowing creek. The colony was detected on 9, 22, and 29 October 2022, although it appeared smaller than usual, but was not seen in an image taken on 8 November, nor any subsequent image. by 12 December all sea ice in the area had vanished, and no Penguins could be observed. This colony appears to have been abandoned before the ice began to break up, although why this was the case is unclear. Very high resolution satellite images suggest that the ice cliff at the edge of the shelf was about 4.5 m high, with a snow ramp between the shelf and the sea ice below at the foot of the ice creek. Satellite images from October suggest that the sea ice beneath this ramp may have broken close to the ice cliff, which would have made it impossible for the adult Penguins to return from the sea to their chicks, forcing them to abandon the colony.

The Rothschild Island colony is the furthest north of the Bellingshausen Sea colonies, being found on sea ice between Alexander Island and Rothschild Island within the Wilkinson Sound embayment. It is a small colony, home to about 700 pairs of breeding Penguins. The colony was directly observed by helicopters deployed from the luxury cruise ship Commandant Charcot on 20 November 2022, which counted 228 adult Penguins, and 820 chicks. Satellite images revealed that there was still ice beneath the colony on 5 and 17 December, although several large patches of open water had appeared within the ice shelf, with the ice around the colony starting to break up on 20 December, making likely that at least some of the chicks fledged successfully. Rothschild Island was close to the heart of the 2022 sea-ice anomaly, and yet the sea-ice appears to have remained sufficiently intact for the Penguins chicks to fledge. It is possible that the sheltered position within the shallow Wilkinson Sound and the many icebergs in the surrounding sea helped to stabilize the sea for longer than at other locations.

Scientists have been monitoring Emperor Penguins by satellite since 2009, and other instances of breeding colonies being lost to rapid ice break-up. Some colony sites, such as the Leda Bay colony in Marie Byrd Land appear to be particularly prone to this, and fail regularly. However, the 2022 event is the first recorded instance of a widespread sea-ice failure affecting multiple colonies before the chicks fledge. Moreover, only one of the Bellingshausen Sea breeding colonies had previously undergone such a failure, suggesting that the 2022 sea-ice collapse event was genuinely significant.

Emperor Penguin colonies have been known to relocate in response to repeated sea ice failure. A colony of Penguins which formerly bred at Halley Bay in the Weddell Sea, but the ice here began to fail regularly from 2016 onwards, prompting the Penguins to relocate their breeding site to a more stable location on Dawson Lambton Glacier, 85 km to the south. However, more widespread failures of the ices shelf due to global warming would make such relocations impossible, although some respite might be offered by refugia such as the Rothschild Island location.

It is difficult to predict exactly how climate change will affect the future of the ice shelf, but all current models suggest that a long-term decline in the ice cover is to be expected. Satellite records of the extent of the ice shelf go back 45 years, with four of the lowest sea-ice coverages recorded since 2016, and the lowest two coverages being in the 2021-22 and 2022-23 seasons. It is possible that this loss is part of an episodic cycle rather than a genuine long-term trend, and answering this question is now a priority for scientists studying the Antarctic climate and sea-ice. The extreme sea-ice loss seen in 2021-22 and 2022-23 is likely to have been influenced by the three years of La Niña conditions in the southern Pacific, which tends to lead to warmer conditions and lower sea ice in the waters off western Antarctica, and that the switch to El Niño conditions in the Pacific in 2023 will lead to a return of cooler conditions and more stable sea ice, but the failures seen in 2022 still represent a warning about the future of Emperor Penguin in a warming global climate.

See also...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Twitter.