The term Later Stone Age is used in South Africa to describe

Holocene stone tool making cultures dating from about 10 000 years ago until

the historical era. From the 1990s onwards efforts have been made to understand

the lifestyle of Later Stone Age hunter-gatherers living in fynbos and

temperate rainforest conditions by studying the morphology of long-bones (arm

and leg bones) from archaeological sites. These bones are highly prone to

modification during an individual’s lifetime, as they serve as supports and

anchors for the limb muscles used in physical activity, and the body is capable

of modifying the bone structure to provide support for repeated activity.

These studies have suggested that both male members of both

populations had strong lower limbs, suggesting that they led very mobile lives

- it was notable that the fynbos individuals were as robust in their lower limb

strength despite the forest individuals living in much more hilly terrain.

However lower limb bones were more developed in forest females than fynbos

females, suggesting that terrain did play a role; both sexes had well developed

lower limbs in forest populations, whereas the fynbos population was sexually

dimorphic (i.e. the sexes were different), with males more robust than females.

The upper limbs were more developed in males in both populations,

suggesting more physical activity was being undertaken by the males than the

females. The males also showed asymmetry of the upper limb-bone development,

this being slight in the fynbos males but quite pronounced in the forest males.

It has been suggested that this asymmetry may reflect the different hunting

methods of the two groups, with the forest hunters favouring spears (thrown

with one hand) while those living on the fynbos preferred light bows (where

both hands are used to hold the bow and draw the string). This has been

supported by studying the limbs of modern athletes, tool assemblages from the

two regions, and records of living San hunters living in the two areas.

The results of these studies have subsequently been used as a base

to compare to other small-bodied Holocene hunter-gatherer populations in the

Andaman Islands, Tierra Del Fuego and Australia. These studies found that the

Andaman Islanders and Yahgan foragers of Tierra Del Fuego showed considerably

higher upper limb-bone development that either South African population,

consistent with a more aquatic lifestyle that involved frequent swimming and

canoeing, while the Australian Aboriginal skeletons showed less development in

both upper and lower limbs, which has been suggested to be indicative of a

lifestyle involving considerably more foraging, at the expense of other

activities.

In a paper published in the South African Journal of Science on 22

September 2014, Michelle Cameron of the Department of Archaeology andAnthropology at the University of Cambridge and the Department of Anthropology

at the University of Toronto and Susan Pfeiffer of the Department of

Anthropology at the University of Toronto and the Department of Archaeology at

the University of Cape Town describe the results of a study of the limb bones

of a new group, Later Stone Age herders from the Orange River Valley of South

Africa.

Map of southern Africa with forest, fynbos and lower

Orange River Valley regions approximated. The fynbosregion is indicated by the

solid outline, the forest region by the small dotted outline and the lower

Orange River Valley by the dashed outline. Black lines indicate approximate

latitude markers and the star indicates the approximate location of

Koffiefontein. Cameron & Pfeiffer (2014).

The bones used in the study came from burials at Koffiefontein and

Augrabies Falls, both are thought to date from around the beginning of the

historical period in South Africa, with the Koffiefontein burial dated to about

390 years ago (i.e. about 1620). The bones are thought to have come from small

bodied herder-foragers, belonging to the same San ethnic group as the coastal

population, and also reliant on stone-aged technologies, though this population

is thought to have had contact with other ethnic groups using different

technologies, and is likely to have had some degree of genetic and

technological exchange. The Orange River Valley has a seasonally arid climate,

with vegetation intermediate between the Sweet Grassveld and Karoo types.

The inland hunter-foragers were found to have higher upper limb

strength than the coastal populations. This is contrary to predictions, since

it was presumed that herding would reduce the need for intense upper limb

activity compared to hunting. This increased strength was seen in both male and

female herders (whereas in the other populations the males had higher upper

limb strengths), and Cameron and Pfeiffer suggest that this may be linked to

increased effort going into foraging in a semi-arid environment where there was

competition with other groups (such as farmers who supplemented their

livelihoods by some foraging).

Both sexes showed some upper limb asymmetry in the Orange River

population. This was less than seen in males from the forest population, but

greater than seen in males from the fynbos population. The cause of this is

unclear, but it is thought to be unrelated to hunting, suggesting that foraging

activity can play a greater role in the development of upper limb-bone

asymmetry than previously thought.

The Orange River Valley population showed a similar level of lower

sexual dimorphism to the fynbos population, with well developed, robust lower limbs

in the males but not the females. This suggests a similar division of

mobility-related labour between the two populations, but does not give any

insight as to what it was. It was previously assumed that the fynbos males were

travelling further afield than the females in pursuit of game, but this is less

likely to have been the case amoung pastoralist herders, where the entire

community is assumed to have moved with the herds.

See also…

One of the most important breakthroughs in palaeoanthropology in the

twentieth century was the discovery of the fossil known as the Taung

Child, the first known specimen of Australopithecus, by Raymond Dart of

the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa in 1924. This discovery refocused efforts to find human

ancestors on the African continent, where many...

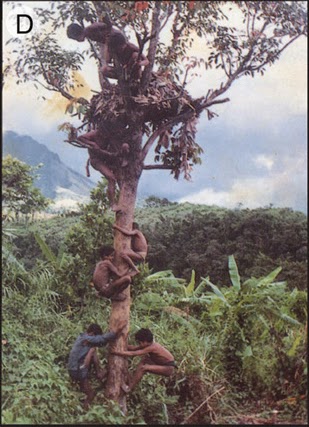

One of the traits that is used to determine that fossil primates are

part of the Human lineage, rather than that which leads to Chimpanzees

and Bonobos (our closest relatives) is the structure of the ankle.

Because of this palaeoanthropologists have tended to assume that the

abandonment of an arboreal lifestyle for a life on the open plains of

Africa was the defining ecological change that led our ancestors to

diverge from those of the Chimps and Bonobos, and that hominids with

human-like...

Skull closure in the Taung Infant. The Taung Infant was discovered by workers at the Buxton Limeworks near Taung, South Africa in 1924 and described in a paper in the journal Nature

by palaeoanthropologist Raymond Dart in 1925. It is the partial skull

and endocast of the brain case of a three to four year old Australopithecus africanus,

the first...

Skull closure in the Taung Infant. The Taung Infant was discovered by workers at the Buxton Limeworks near Taung, South Africa in 1924 and described in a paper in the journal Nature

by palaeoanthropologist Raymond Dart in 1925. It is the partial skull

and endocast of the brain case of a three to four year old Australopithecus africanus,

the first...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.