Plastics are

considered to be one of the major environmental challenges of our

time. They are highly durable synthetic polymers, around 30% of which

are produced for short-life purposes, such as disposable packaging,

and are discarded within a year of being manufactured. Despite the

large number of plastic items being manufactured and then thrown

away, and visible evidence of plastic debris in ecosystems from pole

to pole, environmental scientists for a long time struggled to find

evidence of plastic accumulation (rather than presence) in natural

ecosystems, until they began to examine microplastic particles (tiny

plastic fragments, generally formed from the break-down of larger

items) in sediments and ocean waters, where a steady build-up of

plastics over time has been confirmed. However even these studies

have failed to account for the amount of plastic thought likely to be

present in the environment, leading scientists to suspect that a

large amount of plastic is present but unaccounted for somewhere in

the natural environment.

In a paper

published in the journal Royal Society Open Science on 17 December 2014,

Lucy Woodall of the Department of Life Sciences at The Natural History Museum, Anna Sanchez-Vidal and Miquel Canals of the

Departament d’ Estratigrafia, Paleontologia i Geociències Marines

at the Universitat de Barcelona, Gordon Paterson, also of the

Department of Life Sciences at The Natural History Museum, Rachel

Coppock and Victoria Sleight of the Marine Biology and Ecology Research Centre at Plymouth University, Antonio Calafat, also of the

Departament d’ Estratigrafia, Paleontologia i Geociències Marines

at the Universitat de Barcelona, Alex Rogers of the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford, Bhavani Narayanaswamy of the

Scottish Association for Marine Science and Richard Thompson, again

of the Marine Biology and Ecology

Research Centre at Plymouth University,

discus the presence of microplastic particles in deep-marine sediment

samples collected from a series of sites in the North Atlantic,

Mediterranean and southern Indian Ocean.

The samples

examined were taken from the upper portions of cores gathered for

other studies by the Universitat de Barcelona and the Natural History

Museum over a twelve year period. Because of this the samples were

gathered following different procedures, limiting the amount of

comparison that can be made between the samples. Nevertheless it was

possible to establish the presence of plastics in areas not

previously sampled, and compare the proportions of different plastics

within individual samples.

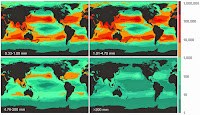

Locations

of sampling sites of bottom sediment and deep-water coral where

content of microplasticswas investigated. Sample depth ranged down to

3500 m, for details see table 1. Sediment was collected by the

University of Barcelona (circles) and the Natural History Museum

(filled squares), and deep-water corals were collected by the Natural

History Museum (open squares). Bathymetry corresponds to ETOPO1Global Relief Model. Woodall et al. (2014).

The areas

sampled included open slopes in the subpolar North Atlantic, the

northeast Atlantic and the Mediterranean, canyons in the northeast

Atlantic and Mediterranean, basins in the Mediterranean and Corals

from seamounts in the southwest Indian Ocean.

All of the

samples were found to contain microplastics in the form of fibres 2-3

mm in length and ~0.1 mm in width. The most abundant fibre was rayon,

which is not strictly speaking a plastic (it is made from dissolved and resolidified cellulose from wood-pulp, rather than hydrocarbons) and which comprised

56.9% of all the fibres found in the study; this is comparable to

results for rayon in previous studies of synthetic fibres ingested by

Fish (where 57.8% of all fibres were rayon) and in ice cores (where

54% of all fibres were rayon). Of actual plastics sampled 53.4% were

polyester, 34.1% were 'other plastics (including polyamides and

acetate) and 12.4% were acrylic.

Plastics

were found at comparable levels to those seen in intertidal and

shallow-marine sediments, and at a rate roughly a thousand times

higher than found in surface waters. Given the vast areas covered by

the deep ocean floor, this is likely to account for a substantial

proportion of the 'missing' plastic predicted to be present in the

natural environment.

All of the

plastics found were heavier than water. At first sight this is what

would be expected as such plastics should sink whereas plastics

lighter than water should not, however for microplastics the

situation is more complex, as such plastics will tend to be held at

the surface by surface-tension, only sinking after becoming colonized

by marine organisms, adhered to phytoplankton and the aggregated with

organic debris and small particles in the form of marine snow.

The impact

of microplastics on deep-sea ecosystems is unclear. In surface and

shallow-marine organisms such plastics have been shown to have

adverse effects both due to their physical and toxicological

properties, and this is likely to be the case also with deep-marine

organisms, but this cannot be asserted confidently without further

study.

See also...

Counting floating plastics in the world’s oceans. Floating plastic is considered to be a major pollutant in the world’s

oceans. It enters the oceans in large quantities from shipping, coastal

communities...

Counting floating plastics in the world’s oceans. Floating plastic is considered to be a major pollutant in the world’s

oceans. It enters the oceans in large quantities from shipping, coastal

communities... Marine litter on the European seafloor. Manmade rubbish (litter) is known to be extremely harmful to aquatic

lifeforms, both as a direct physical hazard (such as nets which continue

to trap and kill Fish long after they have become detached from fishing

vessels or plastic items which resemble food and...

Marine litter on the European seafloor. Manmade rubbish (litter) is known to be extremely harmful to aquatic

lifeforms, both as a direct physical hazard (such as nets which continue

to trap and kill Fish long after they have become detached from fishing

vessels or plastic items which resemble food and... Plastic contamination in Lake Garda, Italy. Plastic contaminants are known to present a threat in many ecosystems,

with particular concern being raised about the oceans, where large

accumulations of plastic are known to be found on ocean gyres (large

rotating currents) and where damage to wildlife from plastic ingestion

is well documented. The effect of plastic contamination on freshwater

ecosystems is less well documented, though studies of...

Plastic contamination in Lake Garda, Italy. Plastic contaminants are known to present a threat in many ecosystems,

with particular concern being raised about the oceans, where large

accumulations of plastic are known to be found on ocean gyres (large

rotating currents) and where damage to wildlife from plastic ingestion

is well documented. The effect of plastic contamination on freshwater

ecosystems is less well documented, though studies of...

Follow

Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.