Humans have been making physical representations of the world around them for at least 40 000 years, principally by creating images and carvings of important things within that world. Maps and plans provide two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional spaces on a reduced scale, to help their users understand and navigate those spaces, and are considered to be a special type of physical representation, resulting from a significant cognitive jump in our understanding of the world. Humans have been modifying their world in a way that implies a degree of advance planning for many thousands of years, but the earliest known plans and maps currently date from the early literate societies of Mesopotamia and Egypt, and even from this era such maps and plans are very rare. How earlier Neolithic communities planned buildings and other communal spaces is unclear.

In a paper published in the journal PLoS One on 17 May 2023, Rémy Crassard of the Laboratoire Archéorient at Université Lyon 2, Wael Abu-Azizeh, also of the Laboratoire Archéorient at Université Lyon 2, and of the Institut Français du Proche-Orient, Olivier Barge, again of the Laboratoire Archéorientt at Université Lyon, Jacques Élie Brochier of the Maison méditerranéenne des sciences de l'homme at Aix Marseille Université, Frank Preusser of the Institute of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Freiburg, Hamida Seba and Abd Errahmane Kiouche of the Laboratoire d'InfoRmatique en Image et Systèmes d'information at the Université de Lyon, Emmanuelle Régagnon and JuanAntonio Sánchez Priego, again of the Laboratoire Archéorient at Université Lyon 2, Thamer Almalki of the Heritage Commission at the Ministry of Culture of Saudi Arabia, and Mohammad Tarawneh of the Petra College for Tourism andArchaeology at Al-Hussein Bin Talal University, describe the discovery of realistic plans for desert kites, Neolithic megastructures believed to have been used as traps for wild Animals, from southeast Jordan and northern Saudi Arabia.

Other representations of kite structures have been found before, but these are somewhat rough in execution, and appear to be generic images, rather than depicting specific kites, whereas the images reported by Crassard et al. appear to be extremely detailed and accurate depictions of specific kites close to the site of the representations. These plans are presumed to have been made by the same people who made and used the kites, as the kites themselves are to large to be directly observed from the ground, and are generally understood by modern observers only once seen from the air. This reveals the degree of planning that went into these structures, and the grasp of the landscape possessed by the people who made it. The plans may have been used in developing hunting strategies involving the traps, as well as in the construction of the traps themselves, and reveal the way in which their makers were able to perceive space and plan communal activities in advance.

Desert kite are megalithic structures comprising two or walls forming a driving line which can range in size from hundreds of metres to several kilometres across, leading to an enclosure with a typical area of about 10 000 m², surrounded by up to 20 pit traps, which can be as much as 4 m deep, into which Animals were driven by the hunters. These are the earliest Human-built large scale structures known, with the oldest examples dating to about 9000 years ago in the pre-pottery Neolithic of Jordan.

Distribution and characterization of desert kites. (A) Desert kite plan from Kazakhstan (Ustyurt Plateau). (B) Desert kite plan from Armenia

(Mount Aragats). (C) Desert kite plan from Jordan (Harrat al-Shaam). (D) Desert kite plan from Saudi Arabia (Khaybar). (E) Distribution area of desert

kites from western Arabia to Uzbekistan. (F) Oblique aerial picture of a desert kite in Jordan (Harrat al-Shaam, photo OB, Globalkites Project). (G)

Oblique aerial picture of a desert kite in Saudi Arabia (Khaybar). (H), (I),

(J) Desert kite pit-traps during and after excavation (of half the pit) in the Harrat al-Shaam region of Jordan. Crassard et al. (2023).

Distribution and characterization of desert kites. (A) Desert kite plan from Kazakhstan (Ustyurt Plateau). (B) Desert kite plan from Armenia

(Mount Aragats). (C) Desert kite plan from Jordan (Harrat al-Shaam). (D) Desert kite plan from Saudi Arabia (Khaybar). (E) Distribution area of desert

kites from western Arabia to Uzbekistan. (F) Oblique aerial picture of a desert kite in Jordan (Harrat al-Shaam, photo OB, Globalkites Project). (G)

Oblique aerial picture of a desert kite in Saudi Arabia (Khaybar). (H), (I),

(J) Desert kite pit-traps during and after excavation (of half the pit) in the Harrat al-Shaam region of Jordan. Crassard et al. (2023).Hunting techniques of ancient Humans (and Hominins) have been studied by archaeologists for a long time, but most of this effort has been directed at weapons technology, with structures such as desert kites only receiving attention in the past few years. The first known desert kites were observed during aerial surveys in the 1920s, but the advent of satellite photography has revealed how widespread these structures are, with examples known from Arabia through the Middle East and Caucasus Mountains and Uzbekistan and into Central Asia, and west across the Sahara as far as Mali and Mauritania. These are believed to have been used in large-scale hunting enterprises targeting whole herds, carried out in desert areas far from permanent settlements. Their appearance, along with the appearance of the first farms in the Near East, indicates the emergence of a highly innovative approach to obtaining resources, in this case meat and other Animal resources, which goes far beyond meeting simple subsistence needs. This marks the beginning of a process by which Humans came to take control of landscapes across the planet.

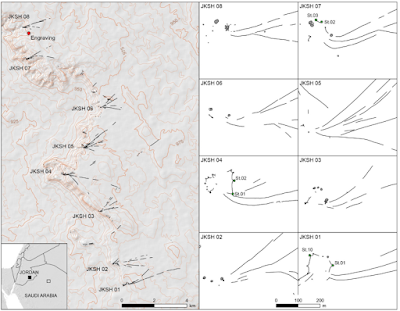

The Globalkites Project website now records over 6000 desert kites, across the Sahara, Middle East, Caucasia, and Central Asia. These are most numerous on the lava fields of s Harrat alShaam in southern Syria, eastern Jordan and northern Saudi Arabia, where in places they reach one kite per square kilometre. Investigation of this area led to the discovery of two rock engravings, which appear to show nearby desert kites depicted to scale. These are on the Jibal al-Khashabiyeh plateau at the eastern edge of the Al-Jafr Basin in south-eastern Jordan and the Jebel az-Zilliyat plateau at the northern edge of the Nefud Desert in northern Saudi Arabia, with the two sites being 267 km apart.

Jibal al-Khashabiyeh is a limestone plateau about 80 km to the east of the city of Al-Jafr, which reaches a maximum elevation of about 1 km above sealevel, and slopes to the east. The plateau is rich in chert, particularly on its upper elevations. There are eight kites known from this escarpment, built from slabs of white limestone and piles of chert. As well as the kites, eight ancient campsites have been found, apparently one per kite, of which three have been excavated by archaeologists, including one, F15, which had previously been targeted by looters, and which yielded the first stone engraving representing a kite.

Jebel az-Zilliyat lies 260 km to the east in Al-Jawf Province, Saudi Arabia, where it forms part of a complex landscape of grabens and faults. Two kites are present on top of the plateau, AB135/AB136 and AB547/AB549, separated by about 3.5 km. During a foot survey of a drainage feature on the plateau, a large engraving apparently depicting both kite enclosures, drawn to scale, was discovered.

The F15 site on Jibal al-Khashabiyeh is a pre-pottery Neolithic site which has been disturbed bu recent looting. Despite this, numerous carved stones are still present, albeit for the most part disturbed and not in their original positions. Many of these conform to the 'ciger-shaped stone' form associated with the pre-pottery Mureybetian Culture, which was found across the Near East from about 10 200 to about 8000 years ago. One notable such monolith, found in June 2015, and measuring roughly 80 cm long, 32 cm wide, and 18 cm deep, and weighing 92 kg, shows a well preserved engraving of a kite.

The edges of the monolith appear to have been shaped with a large hammerstone, while the engraved depiction of the kite shows a mixture of carving techniques. Fine incisions have been used to delineate the borders of the kite, while a pecking tool has been used to etch out the interior area. The limestone of the monolith is soft and chalky, and could have easily been worked with a burin, scraper, or similar chert tool. The surface of the plateau is covered with high-quality chert, much of which shows signs of having been modified by Human activity. The entire interior of the kite has been carved out to a depth of 0.5-1.0 cm, producing a smooth, low relief model.

The carving can clearly be seen to be a kite structure, with the driving lines depicted by two converging carved lines about 40 cm in length, leading to a star-shaped central enclosure about 26 cm in diameter, with a circumference marked bu eight cup-shaped depressions at the tips of the star-points, ranging from 2.5 to 6 cm in diameter, which represent the pit traps of the kite. Part of the right side of the enclosure is missing, either having been lost to weathering or never completed, and, given the overall symmetry of the shape, it appears likely that a ninth cup-shaped depression would have been present in this section. The driving lines are almost parallel, forming a long, straight, corridor-shaped funnel, with a sharp 90° turn and sharp convergence at the entrance to the central enclosure. This plan is common in kites seen in southeastern Jordan, and more rarely in northern Saudi Arabia, but is not known from other kite-assemblages in the region.

Just before the turn in the driving line, a series of five chevrons can be seen running across the width of the corridor, which Crassard et al. suggest may be of symbolic significance, or represents a structure made from lighter materials which have not been preserved, such as a beater-driven hunting spot or a net, or (most likely) represent a break in the topography.

The Jebel az-Zilliyat representation is significantly larger, and was discovered during a survey of rock are in Wadi az-Zilliyat, which cuts across Jebel az-Zilliyat, in March 2015. Two representations of kites are engraved upon a flat surface on the side of a sandstone boulder, which had fallen to the floor of the wadi from an overhanging cliff. The eastern of this pair of posts is readable, but the one on the western side is heavily eroded. The plan here was constructed entirely by pecking at the rock with some sort of hand tool. As at Jibal al-Khashabiyeh, abundant chert is available at the site, from which a suitable tool could have been made. The eastern kite has two short, widely spaced, converging driving lines, measuring 80 cm and 85 cm, respectively. These lead to star-shaped enclosed area 50-60 m across, with a cup-shaped pit 3-5.5 cm deep at the tip of each of its six points. The southernmost two of these cups are around a corner on another face of the rock. The western kite is less clearly defined, with much of the image apparently lost to rock exfoliation, It has two converging driving lines, 85 cm and 60 cm in length, and a star-shaped enclosure 40-45 cm across with at least four cup-shaped depressions. The southern part of this enclosure is missing. It is unclear if the engraving was made on the rock before or after it split from the rock face.

It was not possible to date the engravings at either site, although a radiocarbon date of 8016 years before the present (6930 BC) was obtained from a piece of charcoal at the F15 campsite on Jibal al-Khashabiyeh. This campsite had apparently been disturbed by looters, making the context slightly difficult to interpret, but the site appears never to have been re-used after its initial occupation, so it is likely that the date will be close to the creation of the engraving and nearby kites.

Crassard et al. next set out to compare the designs of the depicted kites to actual kites in the region. All of the eight kites on Jibal al-Khashabiyeh are similar to the design depicted in the engraving, with four having a sharp bend at the point where the converging driving lines meet the enclosure, including the two kites closest to the engraving, JKSH 07 and JKSH 08. In both of these kites the northern driving line remains straight while the southern line curves sharply, to create the bend in the corridor that leads to the enclosure, which is the layout depicted in the engraving. All of the kites on Jibal al-Khashabiyeh have been heavily eroded by water drainage since their creation, so that the star-shaped enclosures can only be identified in three structures; at JKSH 01 eight pit-traps are preserved, and it appears likely that there were originally nine (from the shape of the enclosure and regular spacing of the pits). Kite JKSH 04 also has eight pits preserved, but in this case it is calculated that there were originally another three. At JKSH 07 only three pits remain, but it is thought likely that there were once another six. All three of these kites were excavated, revealing that the pits were stone-faced hollows 143-176 cm deep. One of the pits at JKSH 01 was found to contain five pieces of charcoal, one of which yielded a radiocarbon date of approximately 7000 years.

The engraved rock at Jebel az-Zilliyat lies within a wadi, which runs between two pairs of desert kites, AB547 and AB549 to the west, and AB135 and AB136 to the east. This eastern pair are separated from one-another by 120 m, and have south-facing openings and funnel entrances which run parallel to one-another. AB135 has a large, star-shaped enclosure, typical of kites in this region, with three driving lines, the longest of which is 3379 m. The preservation of this kite is not good, with parts of the structure having been raided for stone to make later stone-aged structures, such as tombs (stone mounds, cairns) and circular structures (pastoral or dwelling enclosures), and more recently other parts having been demolished during gas and oil exploration work.

Despite these problems, a combination of aerial observation and fieldwork has allowed Crassard et al. to build up an accurate idea of the original structure of AB135. The kite has four well preserved pit traps on its northwestern side, and two more on its southern edge, at the edge of a plateau cliff. The eastern one of these is heavily damaged, making it difficult to assess its original structure. A series of further pit traps are present on the northern side, along the structure's driving lines, but these are of a different design, of courser construction, and show a different degree of desert varnish (an orange-yellow to black coating found on exposed rock surfaces in arid environments, composed of particles of clay along with oxides of iron and manganese), suggesting that these were built as add-ons to the original structure at a later date.

Two of the pits at AB135 were excavated; AB135-L01, which yielded some old red altered soil unsuitable for optically stimulated luminescence or radiocarbon dating, and AB135-L03, which produced five fragments of calcitic nutlets of Arnebia sp., from a layer about 10 cm above the bottom of the pit. These fragments yielded a radiocarbon date of approximately 6760 years before the present (about 5670 BC), while a sample of sediment from the bottom of the pit yielded an optically stimulated luminescence date of approximately 7690 years before the present (about 5675 BC); this theoretically should be a date after the trap fell into disuse and began to fill with sediment, providing a minimum age for the structure.

Kite AB136 is better preserved than its neighbour, consisting of two driving lines, 156 m and 54 m in length, plus a 4200 m² enclosure with six pits. None of these pits contained any significant amount of sediment, preventing any useful archaeological excavation of the site.

The pair of kites on the western side of the wadi, AB547 and AB549, appear to have been made using the same construction techniques as the kites on the west, but are much better preserved. These appear to have shared a single pair of driving lines, these being 1549 m and 2623 m in length, while the two traps have enclosures of 5500 m² and 6300 m², respectively, and both have six pit traps. None of the pits of AB547 was considered suitable for excavation, although careful examination of the structure in the field appeared to confirm that it was structurally related to AB549, with the two structures apparently being used together. One of the pits of Kite AB549 was excavated, having 60 cm of accumulated sediment above its base, Here eleven small fragments of Arnebia sp. nutlet were found, one of which yielded a radiocarbon date of 3300 years before the present, or about 1570 BC, while sediment from near the base of the pit produced two optically stimulated luminescence dates of approximately 8040 and 7480 years before the present (about 6025 and 5465 BC). Crassard et al. note that this difference in the dates obtained using the radiocarbon and optically stimulated luminescence dating methods underlines the need to use more than one dating method where possible. In this instance they believe that the anomalous date from the Arnebia sp. nutlets ewas due to the high mobility of such small plant remains, and that the sediment dates provide a minimum age for the trap falling into disuse.

Crassard et al. tested the similarity of the kite engravings to kite structures in the region using a computer-based graph modelling based upon satellite images of the kites. Graphs are mathematical structures, with vertices (fixed points) linked by edges (lines), making them highly suitable for comparing similar structures, and are commonly used in studies of desert kites.

The model used by Crassard et al. compared the kite images to 69 actual kites in the region, concluding that the kites showed between 26.83% and 81.43% similarity to the Jebel az-Zilliyat engraving and between 11.46% and 75.90% to the Jibal al-Khashabiyeh engraving, where 100% would represent an exact match. This suggested that the kite most similar to the Jebel az-Zilliyat engraving is AB135, which is only 2.3 km from the engraving, while the most similar kite to the Jibal al-Khashabiyeh engraving is JKSH 01, which is 16.3 km from the engraving. However, JKSH 01 is only a 75.9% match for the Jibal al-Khashabiyeh engraving, note notably greater than the kite JKSH 07, which is 73.52% similar to the engraving, and only 1.4 km away.

The kite engravings show clear similarities to the actual kite structures, something which can be detected when both qualitative and quantitative approaches are used, and appear most likely to be direct representations of the kite structures closest to them. These carvings are realistic, and surprisingly accurate to scale, given the gigantic size of the kite structures and the difficulty in comprehending their layout without access to modern imaging methods. The engravings appear to be accurate depictions of these large structures intended to help their builders/users develop a mental map of the site.

The Jebel az-Zilliyat eastern engraving shows a very clear similarity to the adjacent AB135 kite, which includes the location of two southern pits on the edge of the escarpment, which in the engraving are represented by two cups on a separate planar surface, giving a three dimensional aspect to the representation. This Jebel az-Zilliyat engraving depicts a pair of kites rather than a single structure, and AB135 is part of a pair of kites, one of two pairs of kites which are close to this engraving. The engravings are reasonably accurate at a scale of 1:175, with compass directions on the immobile boulder matching those of the actual kites.

The Jibal al-Khashabiyeh engraving also shows strong similarities to nearby kites, with the engraving having a similar shape and number of pit traps to these kites, clearly visible when the images are super-imposed, and supported by computer modeled graph plotting of the structures. Notably, the proportions of the corridor leading to the enclosure on the engraving are a very close match for kites JHSH 01 and JKSH 04. This model has a scale of 1:425, with the size of the pits considerably exaggerated in the model compared to the actual kites, which is a reasonable approach, given that they would have been barely perceptible at true scale. Seen in this way. the larger pits still act as useful representations of the place to which Animals should be herded.

This is the first known example of an accurate depiction of a Neolithic structure made by the people who constructed it, and therefore the oldest example of such a plan in Human history. Some older images, from the Upper Palaeolithic of Europe, have been interpreted as schematic maps of the local environment; but these cannot be said to depict a scaled model of the landscape.The oldest European maps are Bronze and Iron Age representations of agricultural land divisions, showing s field features, enclosures, and dwelling areas, as well as road networks, although it is unclear if these relate to the areas where they were found. some more distant environment, or even imaginary landscapes.

The beginning of the Neolithic coincides with the onset of the Holocene in the Near East, and is accompanied by the the building of large, often megalithic, structures, and a subsequent change in social structures which included the domestication of Animals, the appearance of settled communities, the emergence of farming, the development of social hierarchies, and the beginnings of long-distance trade. Despite this, depictions of the spaces in which all these activities took place are rare. A mural from the city of Çatalhőyűk in Anatolia, dated to about 6600 BC, may be a form of map, showing a village and a volcano, possibly a reference of an eruption on Mount Hasan Dağ. A scale model of a reed boat, from Kuwait has been dated to about 5000 BC, while model houses are also known from the Kodjadermen-Gumelniţa-Karanovo culture of the eastern Balkans, dating from about 4500 BC. However, none of these can be considered to be true plans in the way that the kite depictions appear to be. The oldest representations considered to be true plans until now have been from second and third century sites in Mesopotamia, though even these are maps of large areas which do not approach the degree of accuracy seen in the kite engravings.

Prior depictions of the kite structures have been uncovered in Jordan, Syria, and Uzbekistan, although these are not to scale, and have not been dated accurately. While these are not plans in the sense that the new material are, typically being simple, figurative images, these do reveal information about the way in which the kites were used, for example by depicting Animals and Hunters within the kites. These images typically have much reduced driving lines, but greatly exaggerated pits, apparently to emphasize their important function. Furthermore, none of these previously observed figurative kite could be associated with a particular actual kite.

Desert kites are large structures, and building them would have required a good understanding of the topography of the region, and the ability to take into account features such as convex surfaces and breaks in slopes. Thus a plan of the a kite structure could have been used to aid the design of such a structure, as a tool for organizing hunts involving the use of a kite, for some symbolic purpose not obvious to modern observers, or any combination of these.

If the kite engravings do represent construction plans, then they would have formed part of a process that began with studying the topography of the area, and the migration patterns of Animals passing through, before formalizing the plan. It would have also required the kite-builders to have the skills to follow such a design during the construction phase. The engraved kites examined by Crassard et al. show a very accurate scale plan of the kites, but do not show all of the topological features which it would have been necessary to take into account during construction, for which reason, Crassard et al. do not believe that they served as blueprints for the construction of the kites.

The possibility that the plans were used during the organization of hunts seems to be a much more plausible explanation. Such a model, if sufficiently accurate, could be used to plan where hunters would be placed at the outset of a hunt, and to co-ordinate subsequent movements by the hunters, even taking into account what to do in the event of Animals reacting to the hunters in different ways. Seen in this light, the plan is a visual communication device pre-dating the invention of writing, acting as an aid to communication, but probably not useful without some other interaction. Nevertheless, such a plan would be likely to facilitate the development of hunting strategies, and probably led to far smoother hunt operations than would have been possible without it. The plan involves an understanding of the design of the kite and the topography upon which it sits which was probably only available to the builders of the kite, and takes into account features hidden by that topography, such as the pits on the cliff edge at Jebel az-Zilliyat. The chevrons on the Jibal al-Khashabiyeh kite engraving appear to be a symbolic representation of a spatial feature, and while it is difficult to determine what that feature was, this is apparently a very early example of a cartographic practice still in use today.

The plans are not completely to scale, with the most important features, i.e. the pit traps, exaggerated in size, apparently with the intention of increasing the utility of the diagram. Thus the plans represent a compromise reached while trying to find a method of controlling information, in order to make it more possible to pass on to others. In a sense, therefore, these representations can be seen as symbolic as well as practical, with the communicative function being more important than the need for complete accuracy, despite the importance clearly placed upon making an accurate representation.

Despite this use of symbolism, Crassard et al. believe that the primary function of the engravings was utilitarian rather than symbolic purpose, either aiding in the construction or (more likely) use of the kite structures.

See also...