Between 2010 and 2018 the Maski Archaeological Research Project (MARP) searched for further signs of Neolithic activity around the Maski Neolithic settlement, which had been excavated in the nineteenth century. One of the most important finds of this survey was the MARP-79 Cemetery, a large funerary complex beneath an elongated prominence in the southern Deccan region, which appears to have been used for more than a thousand years, from the middle Neolithic into the early Iron Age, showing patterns of both continuity and change across this time interval.

In a paper published in the journal Antiquity on 27 June 2023, Peter Johansen of the Department of Anthropology at McGill University, and Andrew Bauer of the Department of Anthropology at Stanford University present new radiocarbon dates for a number of graves at the MARP-79 Cemetery, and discuss the implications of these for our understanding of the Neolithic/Iron Age cultural transition in southern India.

Archaeologists studying the prehistory of southern India have built up a picture in which the Neolithic/Iron Age transition is an abrupt boundary, probably with an imigrant population or culture completely supplanting the previous one. However, at MARP-79 a more gradual transition can be perceived, with a long-standing Neolithic culture adopting new cultural and technological practices in a more gradual way.

A range of different mortuary practices appear at the MARP-79 Cemetery by the beginging of the second millennium BC, probably indicating social distinctions within the community. These innovations include the nature if grave goods, with ceramic vessels with slip-coatings and polished surfaces appearing and then being replaced by first copper and then iron items, differing materials being used to construct coffins, notably terracotta and burnt organic material, a mixture of singular and shared graves, and different forms of stone grave markings.

The Neolithic of southern India has been studied since the nineteenth century. Initial studies found a wide range of ground and pecked stone tools across the southern Deccan region, which became known as the Stone Axe Culture. As well as Neolithic stone tools, this culture also produced a variety of course, handmade ceramics, notably the Burnished Grey and Dull Red Ware traditions. Studies at sites such as Brahmagiri and Piklihal enabled archaeologists to build up a picture of changing ceramic styles and settlement patterns over the span of the southern Indian Neolithic, which was later refined by the addition of radiocarbon dating and the study of macrobotanical remains.

This Neolithic culture appears to have farmed domesticated Sheep and Goats, along with a number of locally domesticated crops known as the South Indian Crop Package, which includes a selection of pulses and millets. By the beginging of the second millennium BC, northern Indian crops such as Wheat and Barley begin to appear, and become increasingly important over time, and from about 1600 BC, African crop Plants begin to appear. These crop introductions coincide with the appearance of new types of ceramics, notably necked jars.

This appearance of crops Plants which were domesticated in other regions are indicative of this culture being part of an expanding exchange network, which makes it highly likely that they were also exchanging cultural ideas with other areas. This is further supported by the appearance of materials such as carnelian and lapis lazuli, neither of which occur in the region. These changes coincide with the decline and abandonment of the cities of the Indus Valley Civilization in northern India, the adoption of the earliest copper technologies, and the importation of some funrrary practices from the northern Deccan region.

Settlements in the southern Deccan region during the Neolithic typically comprised small villages or camps made up of circular wattle and daub houses, with sites outside the boundary of the settlement used for stone tool preparation, butchery, and the holding of Animals. Some of these settlements had distinctive ash mounds, large piles of ash and vitrified Cattle dung, which may have been associated with periodic feasting.

The area covered by the Maski Archaeological Research Project covers an area of 64 km², and contains four Neolithic settlements. These are the original Maski settlement (MARP-97), a multi-period site 1.5 km to the north of the cemetery, which was first excavated in the 1950s, MARP-64, a newly discovered small settlement running across several adjacent hill terraces which lies 6 km to the northwest of MARP-79, and MARP-155 and MARP-203, which are both interpreted as small hilltop herding camps, which have produced scatterings of stone tools and ceramic fragments, and which lie to the north and south of MARP-79.

The Neolithic burial practices of the southern Deccan region include a number of infant urn burials, and adult pit graves, found both within and outside settlements. The most common of these are infants and sub adults buried in urns withing settlements, although some of these are buried in simple pits without urns. Urn burials typically contain a single individual, although sometimes two individuals are found within the same urn. Burial goods are extremely rare. The form of the urns varies considerably.

Where sites can be established to have gone through several phases of settlement, then burial practices can be shown to have changed over time. Most adults are buried in extended pits, with ceramic grave goods including examples of Burnished Grey Ware and plain terracotta. There is limited variation between these sites, although the orientation of the body can differ, both primary and secondary burials have been found (secondary burials occur when a body is buried, then dug up and buried again), the covering of part or all of the grave with stones, and the presence and variety of grave goods, which can include ceramic vessels, with bowls and spouted jars being the most common, as well as chipped and ground stone tools.

At the Tekkalakota and Ramapuram, where a succession of burial styles can be seen, later graves can be observed to contain a greater quantity of grave goods, including polished ceramics with slip coatings, conforming to the Black-and-Red Ware, Slipped and Polished Black Ware, and Slipped and Polished Red Ware styles, which are otherwise associated with Iron Age Megalithic burials. At Ramapuram later burials comprise stone cairns and cists, and use burned organic material coffins. Here grave goods from these late burials include up to 29 vessels, made from a mixture of styles including Burnished Grey Ware and Black-and-Red Ware, and in some cases copper and iron artefacts. Burned organic coffins and a mixture of ceramic styles were also found during the Maski excavations in the 1950s, as well as Neolithic and Iron Age settlement phases.

However, all of this is based upon a very small number of burials in and around settlements; the known number of burials in the area has long been observed to be much lower than would be expected given the other archaeological remains found, leading to speculation that burials were occurring at other, undiscovered sites. One possible solution to this was presented by the discovery of a possible Neolithic cemetery at Nagarjunakonda in Andhra Pradesh, although this site, which included remains dating from the Lower Palaeolithic to the sixteenth century, including a significant Buddhist temple complex, was flooded by the construction of a dam in the early 1960s, preventing any further investigations.

The MARP-79 Cemetery was discovered in 2012 during a foot-survey of the area by archaeologists from the Maski Archaeological Research Project. A number of burial sites had been exposed by gravel quarrying activities, with graves visible in plan and section within gravel pits. A total of 21 partially exposed burials were found, and it is believed that hundreds more may have been lost due to the quarrying activities, while others may lie undisturbed in other portions of the site. The exposed graves were carefully photographed and drawn, and surface materials were collected. Three graves were excavated in 2018-19.

Thirteen pieces of charcoal, obtained from seven of the graves, yielded radiocarbon dates of between 2472-2335 BC and 1222–1117 BC, enabling Johansen and Bauer to track changes in mortuary practices within the cemetery for over a thousand years. The oldest grave, Burial 12, dates from the Neolithic IB stage, and is a simple pit burial with modest furnishings, including broken micaceous dark grey ceramic fragments, observed in section (from the side).

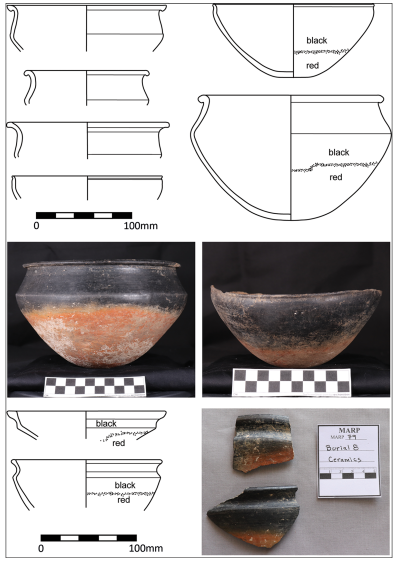

Simple pit burials like this persist past the turn of the second millennium BC, with examples such as Burial 7, which is dated to between 1895 and 1756 BC, and which is another simple pit burial observed in section, containing fragments of slipped and unpolished ceramic. However, by this time other types of burial are also being practiced, including terracotta sarcophagus burials, such as Burial 8, which has been dated to between 1934 and 1700 BC, which in addition had grave goods including Black-and-Red Ware slipped and polished serving vessels and a dolerite ground stone axe. Also present by this stage are burials in which coffins made of combusted organic material contain defleshed coffins, such as Burial 11, which also had grave goods, including five short-necked, globular, red slipped ware jars and seven slipped and polished Black-and-Red Ware serving vessels. Both of these burial types are common in the Iron Age of southern India, and have previously been taken as evidence of a separate, Iron Age culture with more sophisticated burial customs, which was thought to have abruptly replaced the simpler Neolithic culture.

A number of further combusted coffin burials (burials 1, 6, and 19) were dated to the e fifteenth and twelfth centuries BC, apparently continuing the funeral tradition first seen in Burial 11 some centuries previously. Again, the remains within the coffins have been defleshed prior to burial, and the grave goods include slipped and polished serving vessels and globular slipped jars, although Burial 6 also contains four carnelian beads and a copper bangle, and Burial 19 contains a bladed iron tool and some Animal remains (Sheep and/or Goat), and was covered by stone slabs. Similar graves to this have been found at Thapar and Maski, and have been interpreted as evidence of a funerary feasting tradition at the Neolithic/Iron Age transition.

Simple pit burials, and terracotta sarcophagus burials also persist into later phases at MARP-79. For example, Burial 2, which has not been directly dated, contains a terracotta sarcophagus covered by stone slabs, with grave goods including a slipped and polished ware serving vessels and an iron blade, indicating that it must be of Iron Age origin. Iron artefacts and evidence of iron working are known in southern India from at least the fourteenth century BC, while terracotta sarcophagi, including variants with legs and other embellishments are known from elsewhere in the Deccan region, and in wider southern India, with examples dating to as late as the Early Historic Period (300 BC-500 AD).

The use of stone slabs appears to be a progressive development, eventually developing into the megalithic graves of the southern Indian Iron Age. Such slabs are seen in conjunction with a variety of burial types, for example, Burial 3, an otherwise simple pit burial, which has not been dated but which contained a single slipped and polished red ware bowl, was covered by a layer of granite boulders. Burial 20 is an undated pit burial where the pit has been capped with two granite slabs, and these have in turn been covered by a circular cairn of boulders and cobbles, a style reminiscent of Iron Age and Early Historic Period burials elsewhere in southern India, although the grave goods consist only of a copper bracelet and a bone pendant. A similar burial was found at Terdal, with an apparently Iron Age burial containing typically Neolithic ceramics and a copper bangle. This suggests that instead of an abrupt replacement of Neolithic simple pit burials with Iron Age stone circles, cairns, and dolmens, these structures evolved from the pit burials, starting with the capping of the graves with stone slabs.

The MARP-79 Cemetery provides a record of changing funerary practices in the southern Deccan region dating back to at least the Neolithic IIB stage (defined as approximately 2000-1800 BC in southern India), showing that the dead were commemorated in a variety of ways within a single cemetery setting. The site provides the earliest known examples of slipped and polished fine ware serving vessels and terracotta sarcophagi, with later burials also incorporating copper and iron objects. As well as greatly expanding our knowledge of Neolithic burial customs in the region, this is informative about the society carrying out these burials, with more sophisticated burial customs suggesting a larger population, with more people able to put resources into, and participate in a more elaborate burial, and evidence of funerary feasting, which again suggests a larger number of participants, and a population with sufficient resources to arange commemorative ceremonies, probably including feasting. The variety of different burial styles emerging from the Neolithic IIB onwards also suggests a more stratified society, with an uneven distribution of resources.

Notably, these findings challenge the perception that the Iron Age was notably different from the Neolithic in the southern Deccan region, and that this might reflect an incoming, more advanced, society displacing the Neolithic residents of the area, and introducing a new megalithic tomb-building style, at around 1200 BC. Johansen and Bauer's findings suggest a more gradual change-over between the two burial styles, and, importantly, provides radiocarbon dating evidence to support this. The MARP-79 Cemetery also provides the oldest known examples of slipped and polished fine ware serving vessels, dating from several centuries earlier than previously documented examples, further undermining the idea of an Iron Age, megalithic culture invading the area, and bringing this ceramic style with it. Instead this type of pottery appeared at MARP-79 in the Neolithic and persisted for hundreds of years into the Iron Age.

Terracotta sarcophagi, burned organic coffins, stone capped, burials, and cairns, all generally associated with Iron Age and Early Historic Period burials in southern India, appear in the Neolithic at MARP-79, with some of these elements also present at the undated Ramapuram and Tekkalakota burials. This sequential appearance of 'Iron Age' elements in Neolithic burials at MARP-79 runs against the previous interpretation of a static Neolithic culture being replaced by a very different Iron Age culture in southern India. Instead, the picture emerging from MARP-79 is one of a gradually changing culture adopting new technologies sequentially, including metal-working.

MARP-79 records burial customs over a period of about 1500 years, from the Neolithic IIB stage into the early Iron Age. This site is the first Neolithic cemetery in southern India to have yeilded radiocarbn dates. The sequence begins with simple pit burials, later diversifying to include two different burial styles, intact remains being buried within terracotta sarcophagi, and defleshed skeletons placed within burned organic coffins. This suggests a degree of social partitioning within the living community, with different political or social groups with different funurary customs living in the same community. The radiocarbon ages obtained show that these different customs developed in parallel, through the Late Neolithic and into the Early Iron Age. Without the radiocarbon data, this progression would probably not have been identified, with the differing burials more likely to have been identified as coming from different periods. Johansen and Bauer observe that this demonstrates the danger of placing archaeological remains into broad cultural boxes, such as 'Neolithic' or 'Iron Age', which can hide more subtle, gradual changes.

See also...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Twitter.