Mygalomorph Spiders (Tarantulas and related species) are considered to be one of the most ancient groups of Spiders. They have two pairs of book lungs (many other Spiders have lost a pair) and downward pointing, rather than opposable fangs, again considered to be a primitive state in Spiders. Many species of Mygalomorph attain large sizes, all have flattened, disk-shaped bodies (rather than the more globular bodies of most other Spiders), and most are ambush predators.

These Spiders are known to have been present in Australia since before the break-up of Gondwana, with twelve families of Mygalomorphs found there today. Unfortunately, only a single fossil Mygalomorph has been described from Australia to date, Edwa maryae from the Triassic of Queensland, probably due to a combination of these Spiders both having fragile bodies unlikely to be preserved as fossils, and living in an environment unlikely to favour preservation (burrows, mostly in dry areas). Because of this, our understanding of the evolutionary history of Mygalomorph Spiders in Australia is based entirely upon phylogenetic analysis of extant species. By combining these phylogenetic studies with molecular clock analyses, it has been suggested that the group went through a significant evolutionary radiation during the Miocene, which coincides with a period of rapidly changing climate in Australia, with the rainforests which had covered much of the continent being replaced by the arid environment we see today.

Within the Mygalomorphae as a whole, Brush-footed Trapdoor Spiders, Barychelidae, are considered to be the sister group to the True Tarantulas, Theraphosidae, differing from them in being smaller, having shorter spinnerets, and possessing tufts of setae on their feet which enable them to climb smooth surfaces. Brush-footed Trapdoor Spiders are found across all the major landmasses of the former Gondwana, with the exception of Antarctica and New Zealand, but are at their most diverse in Australia, which has led to the suggestion that they might have originated there. However, the most basal genus within the group, Monodontium, is not found in Australia, being found in Singapore, Borneo, and Papua New Guinea, where they inhabit Diptocarp rainforest environments. Members of the genus Monodontium are small for Mygalomorphs, and can be distinguished by the possession of biserial dentition of the paired claws in females, something only present in males in other genera.

In a paper published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society on 15 September 2023, Matthew McCurry of the Australian Museum Research Institute, the Earth & Sustainability Science Research Centre at the University of New South Wales, and the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Michael Frese, also of the Australian Museum Research Institute, and of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, and the Faculty of Science and Technology at the University of Canberra, and Robert Raven of the Biodiversity and Geosciences Program at the Queensland Museum, describe a new species of Brush-footed Trapdoor Spider from the Miocene (16-11 million years old) McGraths Flat fossil sitet located about 25 km north-east of Gulgong in New South Wales.

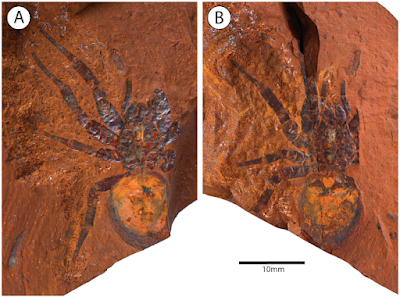

The new species is described from a single compressed specimen, AM F.145559, preserved as part and counterpart in a finely bedded goethite matrix. It is named Megamonodontium mccluskyi, where 'Megamonodontium' is a combination of the modern genus Monodontium, which it closely resembles, plus 'Mega', meaning 'very big', a reference to the specimen being five times the size of the largest known member of the genus Monodontium, while 'mccluskyi' honours Simon McClusky, who found the specimen.

The specimen is split through the carapace and abdomen, so that the chelicerae, eyes, fovea, sternum and spinnerets are unknown, while the e distal ends of the first, third and fourth legs are present only in it the part. This means that it was only realistic to examine the legs of the specimen when attempting to classify it, although this was certainly sufficient to place the specimen within the Barychelidae, based upon the legs being of similar thickness, an absence if strong spines on the first two pairs of legs, a reduced third, or middle, claw on all legs, and the presence of pads around the claws. The specimen lacks claw tufts, a distinguishing feature of the Brush-footed Trapdoor Spiders, but this has only ever been observed in fossil specimens preserved in amber, and therefore cannot be considered significant.

While Megamonodontium mccluskyi superficially resembles some modern Australian Brush-footed Trapdoor Spiders, it retains a number of primitive features not seen in any of these, such as a long patella and teeth on the tarsal claw, making it most likely to be a close relative of the genus Monodontium. However, unlike the tiny Monodontium, Megamonodontium mccluskyi is a moderately large Spider with a carapace length of about 10 mm, making it the second largest fossil Spider ever discovered (behind the 24.6 mm Mongolarachne jurassica from the Jurassic of China).

Neither Megamonodontium nor Monodontium is found in Australia today, suggesting that if they do forma single clade, that clade has since become extinct in Australia. Moreover, the modern Monodontium lives in rainforest environments similar to those which would have been found around McGraths Flat when the fossil-bearing strata there were deposited. Since that time the Australian climate has changed, and the environment become dominated by dryland species such as Casuarina and Eucalyptus. The Miocene is known to have been a major interval for species turnover among Vertebrates, largely as a response to this changing climate, and molecular clock evidence has suggested that the same was true for Mygalomorph Spiders, but the absence of Spider fossils has made it impossible to determine if this was true from direct evidence until now.

See also...

Online courses in Palaeontology.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Twitter.