Mosses (Bryophytes) are simple plants which lack vascular systems to

pump water and nutrients from a root system, instead relying on what

they can absorb through their leaves, and generally only reaching a few

cm in height. This means that they are at their most diverse in moist

habitats, though some species are surprisingly drought-tolerant. Despite

their simple nature, Mosses are an important part of ecosystems the

world over, creating a water-holding layer which covers soil, rocks,

trees and some animals, inside which entire miniature communities of

organisms thrive. Mosses also differ from vascular plants in that they

are haploid (have one set of chromosomes) rather than diploid (have

paired chromosomes); though they have a diploid spore stage used to

propagate the species in the same way that the (haploid) pollen of

vascular plants is.

In a paper published in the journal Cryptogamie Bryologie on 27 March 2019, Maria Bruggeman-Nannenga of Zeist in the Netherlands describes a new species of Moss from Termite mounds in Nigeria.

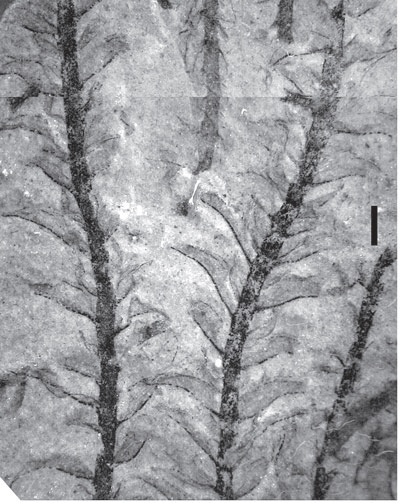

The new species is placed in the genus Fissidens, a group of highly distictive and predominantly aquatic Mosses with a global distribution, and given the specific name ezukanmae, in honour of Izuchukwu Ezukanma, who collected the specimens from which the species is described from Termite mounds in Taraba State, Nigeria. The new species closely resembles the pan-tropical species Fissidens pellucidus, having rather large, clear laminal cells with firm walls and leaves elimbate or with limbidia restricted to the upper leaves (either not having elongate cells which help to support the leaves, or having these only on the upper surfaces)of perichaetial plants (plants in their reproductive stage during which they produce enlarged leaves that surround the reproductive cells). The new species has genuine mammillose cells (hair-bearing cells) and limbidia on both the upper as well the mid leaves of perichaetial stems. Moreover, it has axillary archegonia (spore producing bodies) in addition to the usual terminal perichaetium.

Fissidens ezukanmae: (A) Stem with terminal perichaetium; (B) branched vegetative stem; (C) part of stem with axillary archegonia (upper one left anomalously developed); (D)-(G) leaves; (H) basal part of vaginant lamina of subperichaetial leaf with limbidium; (I) leaf apex; (J) mid leaf; (K) insertion of leaf; (L) detail mid-vaginant lamina; (M) cross-section of stem; (N) cross-section of lleaf with bryoides-type of costa. Scale bars: (A), (B) 1 mm; (C) 0.5 mm; (D) 0.1 mm; (E)-(G) 0.1 mm; (H) 50 μm; (I) 100 μm; (J), (K) 50 μm; (L), (M) 50 μm. Bruggeman-Nannenga (2019).

See also...