Olingos, Bassaricyon, are

small members of the Racoon family, Procyonidae, found in Central and South

America. They are not well understood, as they live in the canopy of dense

forests where they are not easily observed, and are easily mistaken for the

related Kinkajou, Potos flavus.

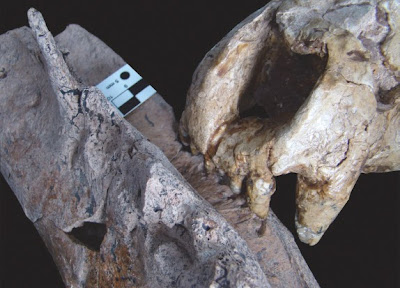

In a paper published in the journal ZooKeys on 15 August 2013, a

team of scientists led by Kristofer Helgen of the Division of Mammals at the

National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC describe a new species of

Olingo from the cloud forests of Colombia and Ecuador.

The new species is named Bassaricyon

neblina, which means ‘fog’ or ‘mist’ in Spanish, a reference to the cloud

forests where it lives; Helgen et al.

also suggest the common name Olinguito, meaning ‘Little Olingo’. The species

was discovered during a genetic study intended to determine the relationships

between the four previously described species of Olingo and other members of

the Racoon Family, using DNA from museum specimens.

Surprisingly, despite all the specimens referred to the new species

having previously been assigned to other species, the new species emerged as a

distinct lineage, which was the sister group to all the other species (i.e. all

the other species were more closely related to one another than to the new

species). More surprisingly still, all the specimens found to belong to the new

species were found to have been collected in cloud forests at altitudes of

1500-2750 m, while all the other specimens were from below 2000 m, suggesting

a clear difference in habitat preference. They were also smaller and more slender

than members of other species, with darker coats.

The Olinguito, Bassaricyon

neblina, in life, in the wild. Taken at Tandayapa BirdLodge, Ecuador. MarkGurney

in Helgen et al. (2013).

The Olinguito is found in cloud forests between 1500 m and 2750 m in

montane cloud forests on the slopes of the Western and Central Andes in

Colombia and Western Andes in Ecuador.

Distribution map for Bassaricyon neblina. Helgen et

al. (2013).

See also…

Glyptondonts were large, heavily armored mammals related to Armadillos

that evolved first appeared in South America in the Miocene, spread to

North America in the Pliocene and became extinct at about the same time...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.