The northwestern part of the Arabian Peninsula was, until fairly recently, believed to have been largely uninhabited until the onset of the Iron Age, in the twelfth century BC. However, recent research has suggested that the area may have been inhabbited for much longer, by peoples with unique cultural identities not seen elsewhere. This research has identified thousands of stone structures across northwestern (and other parts of) Arabia, which have become collectively known as the 'Works of Old Men', and which date from the Middle Holocene (6500-2800 BC) onwards. These structures come in a range of forms, including burrial cairns, tower tombs, 'pendant' tombs, megalithic structures, monumental Animal traps (or 'kites'), and a variety of open-air structures.

One of the forms of open-air structure commonly found in the region is the mustatil (مستطيل), large rectangular structures ('mustatil' is Arabic for 'rectangle'), which comprise two long, parallel walls 20-640 m in length, with two short walls or platforms making up the other sides of the rectangle. Additional dividing long walls are sometimes present, giving the structures the appearance of a European farm gate; they were originally termed 'Gates', but this description has been dropped as it was somewhat confusing. Around 1000 of these structures have now been discovered, scattered across an area of about 200 000 km², between latitudes of 22.989° and 28.064° north and longitudes of between 36.875° and 42.700° west, with the highest concentrations in AlUla and Khaybar counties.

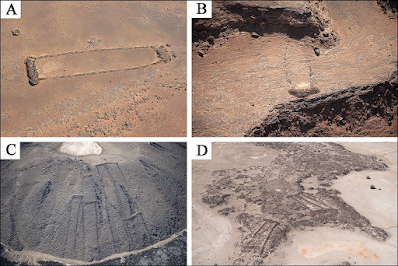

Following a preliminary report in 2017, the Royal Commission for AlUla comissioned the Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia AlUla project to carry out a survey of the mustatil structures of AlUla County, as part of the Identification and Documentation of the Immovable Heritage Assets of AlUla programme. This was later joined by a second project, Aerial Archaeology in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Khaybar, concentrating on the mustatils of Khaybar County. These projects have used publicly available satellite images to identify mustatil structures in remote areas, followed by a series of helicopter surveys, with 1072 mustatils identified from satellite images, 276 photographed from the air, and 39 surveyed from the ground. Several of the mustatils visited were subject to preliminary excavations, revealing features that were not previously known.

In a paper published in the journal Antiquity on 30 April 2021, Hugh Thomas, Melissa Kennedy, Matthew Dalton, Jane McMahon, David Boyer, and Rebecca Repper, all of Classics and Ancient History at the University of Western Australia, present the results of these initial surveys of the mustatils of AlUla and Khaybar counties, Saudi Arabia.

Northwestern Saudi Arabia has exposures of three major geological sequences; the Precambrian volcanic and sedimentary sequences of the Arabian Shield, a sequence of Cambrian-Ordovician sandstones, and a series of Cainozoic basalts, associated with the formation of the Red Sea, as the Arabian Peninsula rifted away from Africa. These different rock-types determine the geomorphology of the region, and therefore the distribution of its archaeological sites.

The largest landforms are in areas where the Cambrian-Ordovician sandstones have been eroded by water to form canyons and mesas. In drier areas, the landscape becomes progressively less varied, as wind erosion takes over from water erosion, till in desert areas there is an essentially flat, sandy landscape, with scattered yardangs (wind-eroded rocky outcrops), often with flattened hilltops, and blackened by desert varnish (a coating of fused clay and manganese particles that forms on rock surfaces not subject to water-erosion).

The Cainozoic Harrat Basalts also form extensive landscapes, notably the Harrats Khaybar, Kura and Ithnayn lavafields, and the Harrat Uwayrid basalt plateau north-west of AlUla. The oldest of these lavafields are Miocene in age, and have flat or gently undulating flow surfaces with few clay pans, while younger, Pliocene-Early Holocene examples form hummocky, ‘whale-back-style’ terrains, with large clay-filled depressions and localised higher relief around volcanic vents.

Mustatils are found on all these landscapes, but their placement and form varies with landscape type.

All Mustatils are distinguished by the presence of a head, courtyard, and base, but some also associated with other features, such as orthostats (standing stones) and circular cells.

The head of a mustatil typically comprises a dry-stone platform, rectangular or sub-rectangular in shape, 10-50 m in length, and 30-120 cm high. These were made from flat slabs of sandstone where these were available, but otherwise chunks of the local rock stacked together. In most of the investigated mustatils, a single oval or rectangular chamber, ranging in size from 2.8 x 2.8 m to 10 x 3 m, was present at the centre of the head. In some cases a doorway, less than 50 cm wide, connected this chamber to the main courtyard. In some instances this doorway had been deliberately blocked off, either with a single capstone or a pile of smaller stones, possibly when the site was decommissioned. Some of the chambers also have other features, notably niches.

The courtyards of mustatils were rectangular, elongate areas, bounded by the head, the base, and the long walls. These appear to have been open spaces when in use; some examples have other structures within the courtyard area, such as smaller enclosures or funerary structures, though these are thought to post-date the original usage.

The long walls comprise two rows of laid stones filled with a rubble core. The laid stones were arranged either horizontally or vertically, with only a single example showing a mixture of horizontal and vertical stones. These walls varied between 50 cm and 3 m in width, and from 30 cm and 120 cm in height.

The base of the mustatils typically had an entrance 30-80 cm in width (sometimes slightly wider), directly opposite the central chamber in the head. Some of these entranceways also appear to have been blocked when the sites were decommissioned, sometimes symbolically with a few stones on either side, sometimes with the entire entrance being infilled.

Sixty five of the 109 sites surveyed from the ground or air had circular cells in front of their bases. These could be discrete, or interlocking, with each site having between three and eight such structures; although the number may actually be higher, as at many sites these have been partially covered by wind-blown sand. At sites with discrete cells, these cells are 1-2 m in diameter, and tend to all be the same size at any given site. At sites with interlocking cells the outermost cells tend to be 1.0-1.3 m in diameter, with the cells increasing in size progressing inwards, so that the largest, inermost cells are 1.8-2.0 m in diameter. These cells are aranged parallel to the base of the mustatil, with a passageway thus formed between the cells and the entrance to the courtyard. In five of the examined mustatils, these passageways had also been blocked, either deliberately or by collapse of the structures. At seven of the examined sites, the cells contained central orthostats (standing stones), fashioned from local stone and 1-1.5 m in height.

The mustatils surveyed on the Harrat Khaybar lava field differed slightly from mustatils surveyed elsewhere, in that they lacked orthostats, but instead had pillars of carefully stacked local stone, probably relating to a lack of suitable marterial to make true orthostats. These pilars occurred in clusters, with up to 50 seen at a single site.

The initial survey of the mustatil sites noted that many had associated 'I'-shaped structures, which have subsequently been shown to comprise low, rubble-filled platforms with an exterior face. These are quite variable in form, varying from structures that are distinctly 'I'-shaped to simple rectangular forms; the variation in shape in these structures closely aligns with variations in the shape of mustatils, with the two structures sharing a similar distribution range, although 'I'-shaped structures are less common, Similar rectangular structures are also known from southern Jordan, although it is unclear if these are related.

A total of 131 'I'-shaped structures have been recorded, of which 73 are adjacent to a larger mustatil. These are typically parallel to the mustatil, and aligned with either the base or a long wall. Up to six 'I'-shaped structures can be associated with a single mustatil, with the 'I'-shaped structures varying in size from 16 x 7 m to 42 x 16 m. These structures never cut across mustatils, and never use stone recycled from them, suggesting that they were in use at the same time, and, therefore, where the two are placed side-by-side, they were somehow functionally related.

The examined mustatils vary considerably in form and shape, but have some consistent feature. Thomas et al. propose they be subdivided into two broad types; 'simple' mustatils with roughly rectangular shapes defined by a head, a base and two long walls, with may-or-may not have an entranceway in the base, but usually lack it, and 'complex' mustatils, which are similar in form, but always have an entrance, which is associated with other structures, such as circular cells and orthostats or pillars. They further note that the 'I'-shaped structures are only ever found in association with complex mustatils.

However, variations are present in both types of mustatil. Notably, additional long walls dividing the courtyard may be present in either simple or complex foems, Most mustatils appear to have been built in a single phase of construction, although some show signs of later modification. Bith simple and complex mustatils are found across the entire range of the structures, with their distribution apparently being random within this range.

The majority of mustatils are built upon exposed bedrock. They do not appear to be oriented towards any particular object or direction, but instead follow the local topography, somthing that varies greatly across the area, depending on the local geology. Where mustatils are built upon slopes, it is always with their long access perpendicular to the slope, while mustatils located on narrow sandstone ridges are arranged to allow the maximum length. On flat ground mustatils show no preferential orientation.

Where possible, the head of mustatils appears to have been deliberately places higher than the rest of the structure, something especially true of mustatils located on the rocks of the Precambrian Shield., but less marked on exposed sandstone outcrops, where the entire structure is typically located on a flat mesa surface. Arranging the mustatils in this way would have been more difficult on the younger volcanic terrains, but even hear these structures are often clustered around vents, enabling the head to be highest. emphasising how important this arrangement must have been. The majority of 'I'-shaped structures and rectangular platforms are also built on slopes. Mustatils placed upon hillslopes are visible from a great distance, which may have been the intention of such placement; those placed upon flat mesas above the wider plain are effectively hidden from sight, but themselves command excellent views. It therefore seems likely that visibility of and from the mustatils was important to their builders in some way.

Mustatils are often found clustered together, with up to 19 individual mustatils found in groups where none is further than 500 m from its neighbour. The mustatils of the Harrat Khaybar are more concentrated into groups than elsewhere, but this phenomenon is found across the entire geographical range of these structures. The reasons for this are unclear, though Thomas et al. suggest that a better understanding of the chronology of the sites construction and use might prove enlightening.

Excavations at the IDIHAF-0011081 mustatil site in eastern AlUla County have revealed a central chamber at the head in which a number of horns and skull fragments from Cattle, Sheep, Goats, and Gazelles have been placed around a central upright stone in the centre of the chamber. These remains are dominated by Cattle, and are assumed to have been some form of ritual sacrifice. No Human remains were found at the site, nor any signs of domestic occupation. Radiocarbon dates were obtained from a tooth and horn, which suggests that the animals from which these came were alive in the sixth millennium BC (Late Neolithic).

A sample of charcoal that was obtained from a looted mustatil located to the south of the Nefud Desert produced a late sixth to early fifth millennium BC radiocarbon date, and faunal remains similar to those from the one excavated by Thomas et al. The type, and positioning, of these remains strongly suggests that the mustatils had a ritual purpose, as does the prominence of the mustatils in the landscape. This is supported by the fact that no mustatil investigated to date has produced any sign of occupation, and absence of any indication of any mustatil having ever been roofed. Orthostats have also been found at other sites in Arabia interpreted as having been used for ritual purposes, which again supports the idea that this was the purpose of the mustatils. The narrow entrances and elongate structures of the mustatils suggest that the rituals carried out within them may have been of a processionary nature, with participants moving in single-file from the entrance to the head.

Stone tools were found at four of the 39 mustatils investigated on the ground. These include a flaked micro core, an obsidian bifacial foliate, and some non-diagnostic flakes and debitage. However, most of the courtyards were devoid of any tools or other cultural material.

Mustatils are commonly found in association with other structures, including, funerary monuments and 'kites'. A total of 118 such associations were found in the aerial surveys, with the mustatils often being overbuilt by, or structurally robbed to build, the other structures. This implies that the mustatils are older than these other structures, and apparently the oldest structures in the area. In some cases, one mustatil appears to overlie another.

There are no known Human burials of similar age to the mustatils in northwestern Arabia. However, many later tombs are closely geographically associated with mustatils, including ringed tombs, with and without pendant tails. These 'pendant' tombs have been dated to between the fourth millennium BC and the second century AD, again supporting the idead that these structures were built after the mustatils, and that in some instances material was looted from mustatils to help build them.

Five examples of mustatils being overlain by 'kite' structures, and one, possible example of a mustatil overlying a 'kite'-structure. Kite structures are again thought to be fourth-to-third millennium BC in age, making them Neolithic in age, although more work needs to be done on these structures.

In all cases mustatils have been built from readily available local stone, which has affected the construction methods used, as well as the appearance and durability. Sandstone tends to split along bedding planes due to natural processes, forming a natural flagstone rock. A similar effect can be obtained using metamorphic schists, which are common in parts of the Precambrian Arabian Shield. In both cases the rock can be extracted in sheets by hand or using wooden tools. This will yield both flagstones from which walls can be made and larger rocks which can be placed upright to produce orthostats. Many of the rocks used in the construction of the mustatils are such sheets, with examples exceeding 500 kg in weight not unusual. Where walls are made from such flagstones they can be fitted together tightly, and are resilient to collapse, unlike walls made from more rounded stones, such as those available on basalt terrains.

The largest Mustatil that Thomas et al. surveyed on the ground was located on the Harrat Khaybar lava field, 50km south of the town of Khaybar. This is 525 m long and made from basalt boulders. Assuming that basalt has a density of 2500 kg/m³, Thomas et al. estimate that the construction of this site would have required the moving of 12 000 tonnes of rock, with the individual rocks used weighing from 6 to 500 kg.

Methods of estimating the amount of time and labour needed to construct stone monuments have been developed by archaeologists working on Mayan structures in the New World, and there were applied by Thomas et al. to the mustatils. This led them to conclude that a group of ten people could construct a 150 m mustatil in twe-to-three weeks, and that a 500 m mustatil could be built by a team of fifty people in about two months. Thus, most of the mustatils could have been built by small groups of workers in a relatively short period of time, and even the largest could have been constructed by a family group in a few months, and potentially much less time if several family groups worked together. The construction of mustatils could, therefore, have formed part of a broader Neolithic development of community and power structures, and possibly served as a means of maintaining social cohesion amoungst widely dispersed and/or nomadic pastoralist communities.

Understanding why the mustatils were built requires a wider understanding of the culture that produced them. They appear to date entirely from the Late Neolithic, and possibly represent a new culture moving into the area, as climatic variations in Arabia during the Late Pleistocene and Ealy Holocene are thought to have driven repeated colonisation of, and withdrawal from, areas by different Neolithic peoples, resulting in distinctive regional cultures across the landmass. The relationship between the mustatil-building culture and the Holocene Humid Phase (roughly 8000–4000 BC) is unclear.

The ritually deposited Cattle remains at site IDIHA-F-0011081 appear to represent the oldest known evidence for Cattle on the Arabian Peninsula, and therefore the arrival of an important economic resource for Neolithic pastoralists. Cattle are important in rock art from the Arabian Late Neolic, but the earliest known evidence for Cattle comes from Shi’b Kheshiya in Yemen, where there are a number of structures thought to have been associated with Cattle, and dates to about 4400 BC, making it about 900 years younger than site IDIHA-F-0011081.

The large size of the mustatils, and the way in which their makers were able to construct to a common plan over a very wide area, suggests that these structures were imoportat the their makers, and conveyed some connection with the land, possibly serving as terrirory boundaries, or sites of some ritual right of passage. On other parts of the peninsula, burial structures may have served a similar function,

No structures closely resembling mustatils are known from anywhere else, although a number of large, rectangular, open-air 'sanctuaries' are known from the Negev Desert, and these also date to the sixth millennium BC. However, while these share the same basic form as the mustatils, they show no similarity in placement or building methodology, making it unclear if there is any relationship. What the mustatils do appear to be is one of the first examples of a strictly ritual structure in the Neolithic of the Near East.

Mustatils are found across a wide area of northwestern Arabia, showing a remarkable level of structural conservatism, albeit with adjustments for local geology. Understanding the context in which these structures were built is clearly highly important for understanding the developing cultures of the Middle Holocene in the area, and the number of these monuments may indicate that this landscape may have supported a far higher population at this time than was previously thought.

See also...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Twitter.