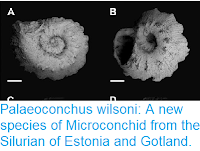

Brachiopods (or Lampshells) superficially resemble Bivalve Molluscs,

though they are not closely related. They were abundant in the seas of

the Palaeozoic, often dominating benthic faunas, but today are

comparatively rare, and seldom seem outside the tropics. Brachiopods

have a filter feeding apparatus called a lophophore, unlike anything

found in any Mollusc, but also found in Bryozoans and Phoronid Worms.

This is encased with in a shell with two valves, each symmetrical about a

midline, but not necessarily the same as each other, along with the

rest of the organs of the body; there is typically remarkably little

flesh to a Brachiopod compared to a Mollusc with a shell the same size. Brachipods formed a dominant part of benthic invertebrate communities during the Palaeozoic, but became steadily rarer during the Mesozoic Marine Revolution, during which the appearance of many types of grazing invertebrates, such as Starfish, carnivorous Snails, and Decapod Crustaceans, caused many earlier benthic groups to decline or disappear. Brachiopods are still around today, but are rare, with most species found either in deep waters or cryptic environments such as caves.

Albano and Stockinger used a vacuum pump system to suck up organisms from the dense rhizome (root) mat layer of a meadow of Neptune Grass, Posidonia oceanica, at depths of between 5 and 20 m off the south coast of Crete. This environment is difficult to sample using traditional methods such as dredging or handpicking by divers, due to the dense nature of the Neptune Grass, and therefore little is known about the organisms which live their.

A meadow of Neptune Grass, Posidonia oceanica, note the density of the colony. Alberto Romeo/Wikimedia Commons.

This method revealed colonies of two species of Megathyrid Brachipod, Joania cordata and Argyrotheca cuneata, living on the rhizomes of the Neptune Grass, as well as many shells of these species, plus large numbers of a third species, Megathiris detruncata, and a single specimen of a fourth, Novocrania anomala, in the sediments below. None of thee species reaches more than a few millimetres in size, making them more-or-less impossible for divers to spot among the dense Neptune Grass.

Living Brachiopods from the rhizome layer of the Posidonia oceanica meadow in Plakias, southwestern Crete Greece. (a) Joania cordata on plant debris, from a depth of 20 m; (b) Argyrotheca cuneata on plant debris, from a depth of 20 m; (c) Joania cordata inside the aperture of an empty shell of the Gastropod Bittium latreillii, from a depth of 10 m; (d) Joania cordata beneath the Bryozoan Patinella radiata, from a depth of 10 m; (e) Joania cordata attached to the Foraminiferan Miniacina miniacea, from a depth of 20 m; (f) Argyrotheca cuneata attached to the Foraminiferan Miniacina miniacea covered by a Bryozoan colony of Hippaliosina depressa. Scale bar is 1 mm. Albano & Stockinger (2019).

Most living populations of Brachiopods are found below the photic zone, or in cryptic environments such as caves (or shipwrecks), environments where predator numbers are lower, but so is nutrient availability. As such Brachiopods are considered to be minor parts of modern ocean faunas. The discovery of Brachiopods living in a dense population within a Seagrass meadow challenges this assumption, as such meadows are one of the most widespread habitats in shallow marine environments, suggesting that Brachiopods could be much more abundant today than is generally realised.

See also...

%20(1)%20(1).png)