Palms are an important component of modern tropical ecosystems, with

the majority of species (~90%) restricted to tropical rainforests, where they

are important understory plants. Palms reach their maximum diversity today in

Asia (over 1200 species) and the Americas (about 730 species), but are much

less diverse in Africa (about 65 species, less than Madagascar), with only one

species native to Europe, though it is thought that they were more diverse in

these areas prior to the cooling and aridification of the Plio-Pleistocene.

Palms are poorly adapted to cooler or drier climates, as they have large

evergreen leaves and are incapable of going through dormant periods like many

plants, so that they tend to require high levels of sunlight and water all year

round and are unable to cope with frost or snow. However one group within the

Palms, the Coryphoideae, is more tolerant of cooler and drier conditions than

others, with many species found in arid or warm temperate climates.

In a paper published in the journal PLoS One on 13 November 2014, Rashmi Srivastava and Gaurav Srivastava of the Cenozoic Palaeoflorist Laboratory at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany and David Dilcher of the Department of Geology at

Indiana University describe a new species of fossil Coryphoid Palm leaves from

the Deccan Intertrappean beds of Madhya Pradesh, India.

The Deccan Traps are a massive are of flood basalts covering about

500 000 km2 of modern India, and thought to have originally covered

around 1 500 000 km2 of what is now India and the western Indian

Ocean. These basalts were produced by extensive volcanic eruptions that began

about 69 million years ago and persisted to about 61 million years ago, peaking

between 67 and 65 million years ago. The timing of this volcanic activity leads

to the inevitable conclusion that it must have played a role in the End Cretaceous

Extinction, about 65.5 million years ago, although scientists differ in the

weight they give to this and the major impact event that took place at Chixulub

(check) on the Yucatan Peninsula at the end of the Cretaceous as causes of this

extinction.

The Deccan Intertrappean beds are layers of sedimentary rocks

between different layers of basalts within the Deccan Traps. These often

represent highly fossiliferous lacustrine (lake) and fluvial (river)

environments, which produce large numbers of plant fossils. Clearly these

fossils present a potential wealth of knowledge for understanding extinction

patterns at the end of the Cretaceous, although interpreting this has proven to

be difficult, as there appears to be no direct correlation between episodes of volcanism

and plant extinctions.

Map of India showing fossil locality. (A) Map of India

showing extent of Deccan traps. (B) High resolution map showing the fossil

locality. Srivastava et al. (2014).

The Palm leaves described by Srivastavaet al. are place in the organ genusSabalites (in palaeobotany an organ

genus is applied to a part of an extinct plant, such as a leaf or a root, in

the accepted knowledge that other parts of the plant may be named separately;

this is because whole, intact plant fossils are a rarity, and palaeobotanists

need to be able to name the separate organs to havereference points for other

work), and given the specific name dindoriensis,

meaning ‘from Dindori’; they were collected from the Ghughua Fossil National

Park in the Dindori District of Madhya Pradesh. These beds are thought to be

from the end of the Cretaceous to the beginning of the Palaeocene (Maastrichtian–Danian).

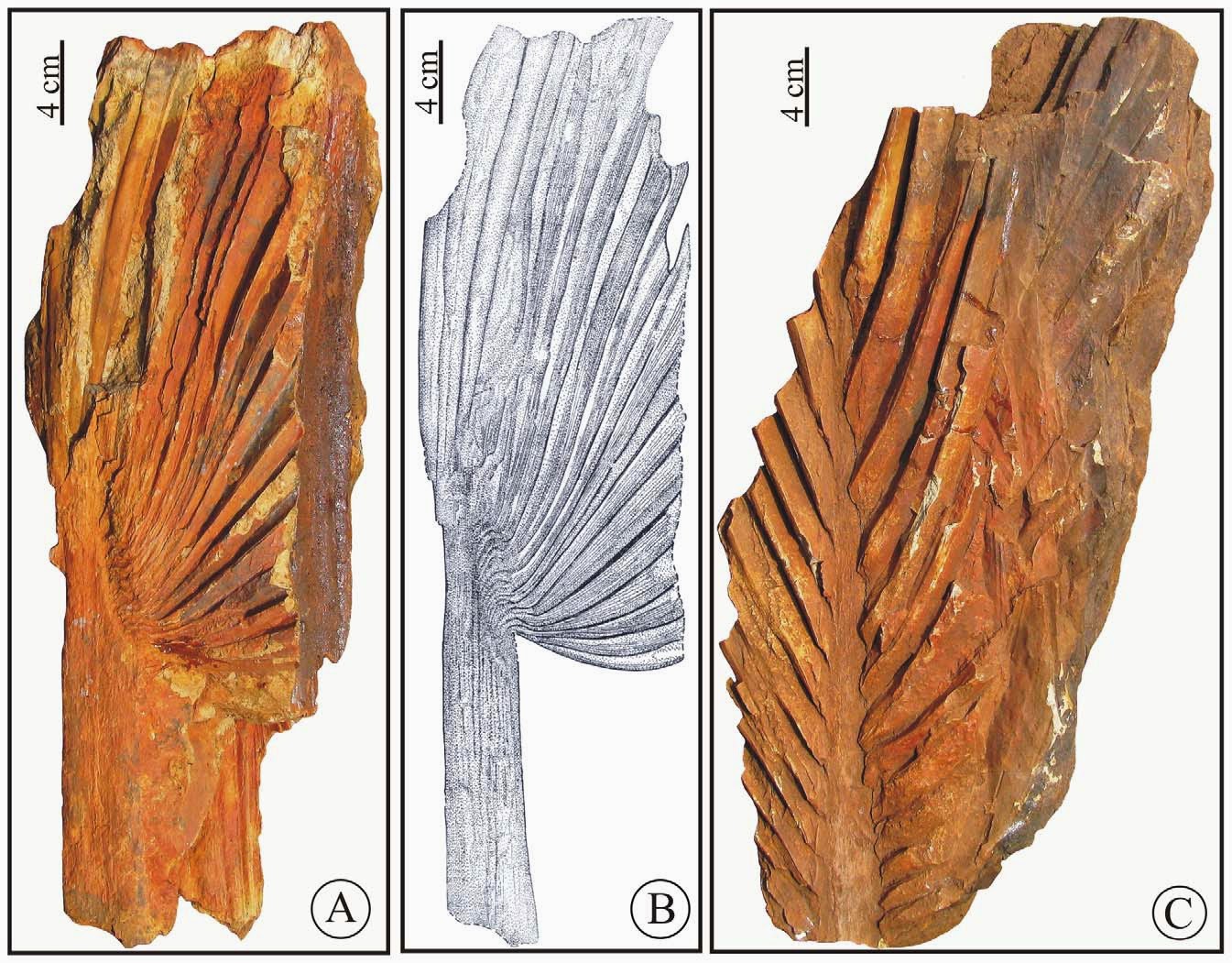

Sabalites dindoriensis.(A) Basal portion showing thick costa. (B) Drawing of the same

fossil. (C) Middle portion of the fossil leaf showing leaf segments attached to

costa. Srivastava

et al. (2014).

The species is described from five specimens, the largest of which

is roughly 45 x 13.5 cm. None of these specimens are of whole leaves, with one

specimen (the largest) showing part of the base of the leaf and the stem, two

from the middle part of the leaf and two from the tip.

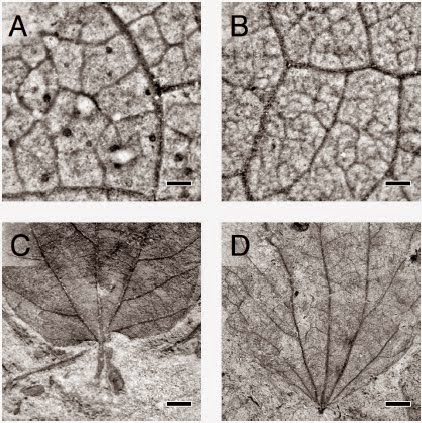

Sabalites dindoriensis.(A) Specimen seems to be of apical portion showing faint

impressions ofrachilla like structure (white arrows). (B) Enlarged portion of

the same specimen showing rachilla like structure (white arrows). (C) Specimen

seems to be of middle portion. (D) Enlarged portion showing high order

venation. Srivastava et al. (2014).

The first Palms are thought to have appeared in Laurasia (Eurasia and

North America) about 100 million years ago, with the Coryphoids originating

about 87 million years ago. India has a high number of endemic Palm species

today, but was an island continent in the Late Cretaceous, and it has generally

been thought that Palms first reached India in the Miocene, when it began to

collide with Eurasia. The presence of Palm fossils in the Deccan Intertrappean

beds clearly indicates that this was not the case, and instead Srivastava et al. suggest an alternative scenario,

in which Palms dispersed from Europe into Africa and then across the (narrower)

Indian Ocean to India by the end of the Cretaceous.

Palaeogeographic map at 65.5 Ma showing possible

dispersal path of Coryphoideae from Europe to India via Africa (red broken

line). Srivastava et al. (2014).

See also…

Madagascar is considered to be one of the world’s biodiversity

hotspots. The island has an area of 592 750 km2 and is located in

the southern Indian Ocean, giving it a tropical climate with a diverse range...

How changes in Plant ecology shed light on the End Cretaceous Extinction Event.

How changes in Plant ecology shed light on the End Cretaceous Extinction Event.

One of the two main theories that seeks to explain the extinction

event at the end of the Cretaceous postulates that a large bolide

(extra-terrestrial object such as a comet or asteroid) smashed into the Yucatan Peninsula

in Mexico

close to the modern town of Chicxulub, resulting in a devastating explosion and

long term climate change. Such an event would have led to a...

Sixty-five million years ago the world was a very different place; the land was dominated by giant dinosaurs, pterosaurs filled the skies and the seas swarmed with giant marine reptiles and ammonites. Then overnight (in geological terms) everything changed. The non-avian dinosaurs disappeared, as did the pterosaurs, ammonites and all the marine reptiles except turtles and sea-snakes (crocodiles have since...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Sixty-five million years ago the world was a very different place; the land was dominated by giant dinosaurs, pterosaurs filled the skies and the seas swarmed with giant marine reptiles and ammonites. Then overnight (in geological terms) everything changed. The non-avian dinosaurs disappeared, as did the pterosaurs, ammonites and all the marine reptiles except turtles and sea-snakes (crocodiles have since...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.