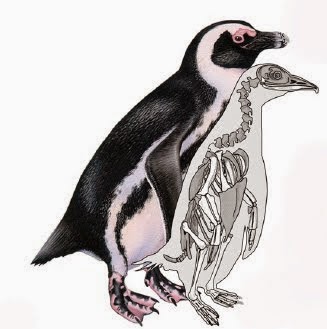

African Penguins, Spheniscus demersus,

breed at a number of sites along the coasts of South Africa and Namibia. The

species is considered to be Endangered under the terms of the InternationalUnion for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species,

following a 70% drop in the total population of the Birds between 2001 and

2013. This has been attributed to changes in the distribution and availability

of the Penguin’s two main prey species, the Sardine, Sardinops sagax, and the Anchovy, Engraulis encrasicolus, in part due to competition with the local

purse-seine fishery.

The populations of African Penguins near Cape Town were hit by two

large oil spills in 1994 and 2000, resulting in the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (SANCCOB) capturing a large number of

adult birds for de-oiling, and the chicks of these birds for hand rearing

(since the adult birds were unable to feed their young while being treated for

oil contamination). This hand rearing procedure was largely successful, and was

from 2001 onwards extended to abandoned chicks from Robben and Dyer Islands.

African Penguins, Spheniscus demersus. SANCCOB

Chicks may be abandoned due to the death of their parents, flooding

of the nest site or because the parents enter their annual mount before the

chicks are ready to fledge. The annual moult in African Penguins occurs at the

beginning of summer, and cannot be delayed, adults with unfledged chicks

beginning to moult in response to moulting in other birds around them. Chick fledging,

on the other hand, is driven by food availability, with chicks that have not

received sufficient food failing to fledge before the onset of the moult being

abandoned. African Penguins are long-lived birds which typically rear two

broods per year, so the adult birds will not endanger their health (and

potential future breeding success) for these late fledging birds.

In a paper published in the journal PLoS One on 22 October 2014,

Richard Sherley of the Animal Demography Unit and Marine Research Institute at

the University of Cape Town, the Bristol Zoological Society and the Environment and Sustainability Institute at the University ofExeter, Lauren Waller of the Animal Demography Unit and Marine Research

Institute at the University of Cape Town and CapeNature, Venessa Strauss of

SANCCOB, Deon Geldenhuys also of CapeNature, Les Underhill, also of the Animal

Demography Unit and Marine Research Institute at the University of Cape Town

and Nola Parsons, also of SANCCOB discuss the results of two large-scale

interventions on Dyer Island, following the mass abandonment of chicks be

adults that had begun to moult before they fledged in 2006 and 2007.

In 2006, 113 chicks had been collected from Robben Island, 34 from

Stoney Point and 19 from Dyer Island prior to 15 October, when the adults on

Dyer Island began to go into moult en masse, and the decision was made to

remove all the surviving chicks from Dyer Island for hand rearing, a total of

668 chicks being collected between 16 and 21 October. Not all of the adults on

Dyer Island had entered moult at the time when this occurred, but since

moulting in adults is triggered by the proximity of moulting in nearby adults,

and the removal of large numbers of chicks was deemed to be sufficiently

disruptive to the life of the colony that the abandonment of further chicks was

likely, the decision was made to remove all chicks from the colony.

In 2007, 7 chicks had been removed from Robben Island and 47 from

Stoney Point by 27 October, when the adults on Dyer Island again began to go

into moult en masse, and it was again decided to remove all remaining unfledged

chicks from the island; on this occasion 427 chicks being collected.

Map of the Western Cape, South Africa, showing the locations

of the main African penguin breeding colonies (black circles) mention in the

text and the location of SANCCOB (black square) in relation to Cape Town (white

circle). Sherley et al. (2014).

Artificial feeding can be a problem for some bird species, but Sherley et al. report that African Penguins

respond well to the procedure. This is probably due to the natural biology of

the birds; after an initial period of guarding when the chicks are very young

both parents engage in collecting food for the young, which spend extended

periods of time sitting alone waiting to be fed, and seem to be largely

indifferent to who (or what) feeds them as long as food arrives. The captive

birds accepted a mixture of fish-paste laced with vitamins and whole fish

without any problems.

Disease control at in captive reared Penguins proved to be much more

problematic. Many of the captive birds were afflicted by bacterial and fungal

infections of the respiratory system, probably caused by overcrowding at the

treatment facility (the rearing of this large a number of chicks had not been

attempted before, and was not anticipated prior to the first mass-abandonment).

The birds were also afflicted by two insect-borne diseases, avian pox and avian

malaria, and the treatment facility attracted large numbers of Flies and

Mosquitoes. A variety of screens, traps and insecticides were used to try to

control the insects, with limited success. In 2008 a new fly screen system was

introduced that appears to be much more effective, but no mass abandonment of

chicks has occurred since then, so it is unclear how well the new system would

cope with such an occurrence. Finally many of the chicks were afflicted with bumblefoot

(pododermatitis) a disease of the feet which is not usually fatal but which is

highly unpleasant for the chicks. This can be easily treated by making the

chicks walk through water laced with disinfectant and providing them with

different substrates on which to stand, but the facility was not equipped to do

this for the large number of birds admitted in 2006 and 2007.

Of the 841 chicks admitted in 2006, 766 were subsequently released,

and of the 481 chicks admitted in 2007, 351 were released. Since chicks are

known to move freely between populations before choosing a mate and a nesting site,

rather than strictly returning to the parental nesting site to breed, it was

not deemed necessary to return all the chicks to Dyer Island for release, and

the chicks were released variously from Robben Island and Dyer Island, or in

some cases into the sea near Robben Island. All the chicks were ringed for

subsequent identification, and chicks released in 2006 and 2007 have

subsequently been sighted breeding on Dyer Island, Robben Island, Dassen Island

and at Stoney Point. It is estimated that 14% of the captive reared chicks went

on to enter the breeding population, which compares favourably with the 11% of

chicks that are expected to enter the breeding population from naturally reared

broods.

Sherleyet al. observe that

Penguins seem to be particularly well suited to captive rearing programs, and

recommend that the process could be used to increase numbers of other

endangered Penguin species reaching maturity, and potentially to re-establish

historic breeding populations that have been lost or establish new colonies as

a defence against shifting prey-fish distributions. However they caution that

extreme attention must be paid to disease control in such programs, to avoid

introducing diseases to the wild population that could further accelerate the

decline of already threatened species.

See also…

An operation to recover oil from a ship which sank of the coast of

Richards Bay, KwaZulu Natal, on Monday 19 August 2013, is due to begin

today (Thursday 22 August). The VS Smart, a 230 m Greek...

Penguins are thought to have originated in New Zealand and subsequently

spread to other parts of the Southern Hemisphere. Certainly both modern

and fossil Penguins are at their most diverse in New Zealand. A large

number of fossil penguins have been described from New Zealand,

although, as is often the case with fossil birds, many of these are

fragmentary in nature.

A single species of Penguin, Spheniscus demersus, or the Blackfooted Penguin, lives in Southern Africa today, though two species, Nucleornis insolitus and Inguza predemersus

are known to have lived there in the Early Pliocene. It has generally

been assumed that the modern Penguins are descendants of the fossil

penguins, though since they are also clearly closely related to other

Penguins of the genus Spheniscus...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.