The Ediacaran Fauna comprises a group of fossils from the Late

Ediacaran Period, found at sites around the world and pre-dating the Cambrian

Explosion, which is considered to indicate the origin of the majority of modern

animal groups, and in particular those with mineralized skeletons. Some

biologists have suggested that these organisms represent an entirely separate

experiment in multicellular organization (referred to as Vendozoans), and that

they are not ancestral to any modern animals (collectively referred to as

Metazoans). Others see similarities between some members of the Ediacaran Fauna

and extant animal groups, and suggest that they fossil assemblages contain

members of the Phyla Porifera (Sponges), Cnidaria (Jellyfish, Corals, Sea

Anemones etc.) and even groups such as Molluscs and Echinoderms. Under this

second hypothesis the Ediacaran fossils represent true Metazoan Animals,

although some of them probably belong to groups now extinct.

In a paper published in the journal PLoS One on 3 September 2014, Jean

Just, Reinhardt Møbjerg Kristensen and Jørgen Olesen of the Section ofBiosystematics at the Natural History Museum of Denmark (Zoological Museum) at

the University of Copenhagen, describe two enigmatic animals from the

Australian continental shelf, which do not appear to belong to any known animal

group, but which do show some resemblance to some members of the Ediacaran

Fauna.

The specimens were collected by the Australian National Facility

Research Vessel ORV Franklin in 1986, from two site on the Australian

continental shelf at depths of 1000 and 400 metres, as parts of bulk samples

containing benthic bathyal invertebrates with a sled which collected both

sediments and organisms from the seafloor. Larger specimens were removed by

hand, then the samples were passed through a number of sieves, before washing

and storing in 80% ethanol for later analysis. The specimens were taken to

Canberra for examination, where they were inadvertently treated with absolute

alcohol instead of 80% ethanol, resulting in some damage to the specimens

(strong shrinkage and rendering the specimens glassy and brittle), and

furthermore making them unsuitable for genetic analysis. Once the uniqueness of

the specimens was realised, the collection sites were revisited in the hope of

collecting more, but both locations were found to be bleached (denuded of

epibenthic invertebrates)

The specimens are considered to belong to a new genus, named Dendrogramma in reference to its

branching gastric system, and this is placed within a new family, named Dendrogrammatidae.

It is considered highly likely that these animals belong to a completely new

Phylum, but due to the damage caused to the specimens, the lack of genetic data

and the inability to locate any further specimens, Just et al. refrain from establishing any higher taxonomy.

The first new species is named Dendrogramma enigmatica,

in reference to its enigmatic nature. The species is described from 13

specimens collected from a depth of 1000 m off Point Hicks and 1 specimen

collected from a depth of 400 m off the Freycinet Peninsula on Tasmania. These

are roughly mushroom-shaped, with a disk-shaped body and a stalk. The mouth is

at the end of the stalk, connected to the body by a gastrovascular canal or

pharynx within the stem, then branches numerous times within the body disk. The

disk has a distinct notch and the mouth has two lobes. The largest specimen is

11 mm in diameter and has a 7.8 mm stem.

Dendrogramma enigmatica. (A, B) Lateral views; (C) aboral view, (D) adoral view. Photographs

taken after shrinkage. Just et al. (2014).

The second species is named Dendrogramma discoides,

in reference to the shape of its body-disk, which lacks the notch seen in Dendrogramma enigmatica. This species is

described from four specimens collected from a depth of 1000 m off Point Hicks.

The largest is about 17 mm in diameter, with a 4.5 mm stalk. This species has

three lobes to the mouth rather than two.

Dendrogramma discoides, (A) aboral view. (B) Enlargement of (A) showing gastrovascular canal

(stippled) of stalk (pharynx) and point of connection to the first branching

node of gastrovascular system of the disc. (C) Oblique oral view of trilobed mouth-field

with mouth opening in centre; entire pharyngeal part of the gastrovascular

system is shown. Just et al. (2014).

The new animals have a simple diploblasic bodyplan, with two dermal

layers, the epidermis (outer skin) and the gastrodermis (lining of the

gastrovascular system) separated by a gelatinous mesoglea (tissue thought to

have a structural role, helping the animal keep its shape, but no other

function). This is seen in two other groups of living animals, the Cnidarians

(Jellyfish etc.) and the Ctenophores (Comb Jellies). However they have no other

anatomical features seen in either of these groups.

Traditional classifications of modern animals have always regarded

the Porifera (Sponges) as the sister group of all other animals, due to their

lack of a permanent body structure or tissue (a Sponge squeezed through a sieve

and broken into its component cells can simply reassemble itself) and

resemblance to colonies of the single-celled Choanoflagellates. The Cnidaria

and Ctenaphora, having similar levels of organisation are considered to be

ancient branches on the animal family tree, predating the origin of the Bilateria

(the group including all familiar animals other than Cnidarians, Sponges and

Comb Jellies). However recent genetic studies have suggested that the

Ctenaphores might be the most ancient branch on the animal family tree,

diverging before the Sponges and reaching their current level of organization

through parallel evolution rather than a close relationship with the

Cnidarians.

This clearly has implications for the phylogenetic position of Dendrogramma. If the Cnidaria and

Ctenaphora are closely related then Dendrogrammai s

likely to be closely related to both, but if they are only distant cousins,

then the position of Dendrogramma on

the animal family tree is harder to determine.

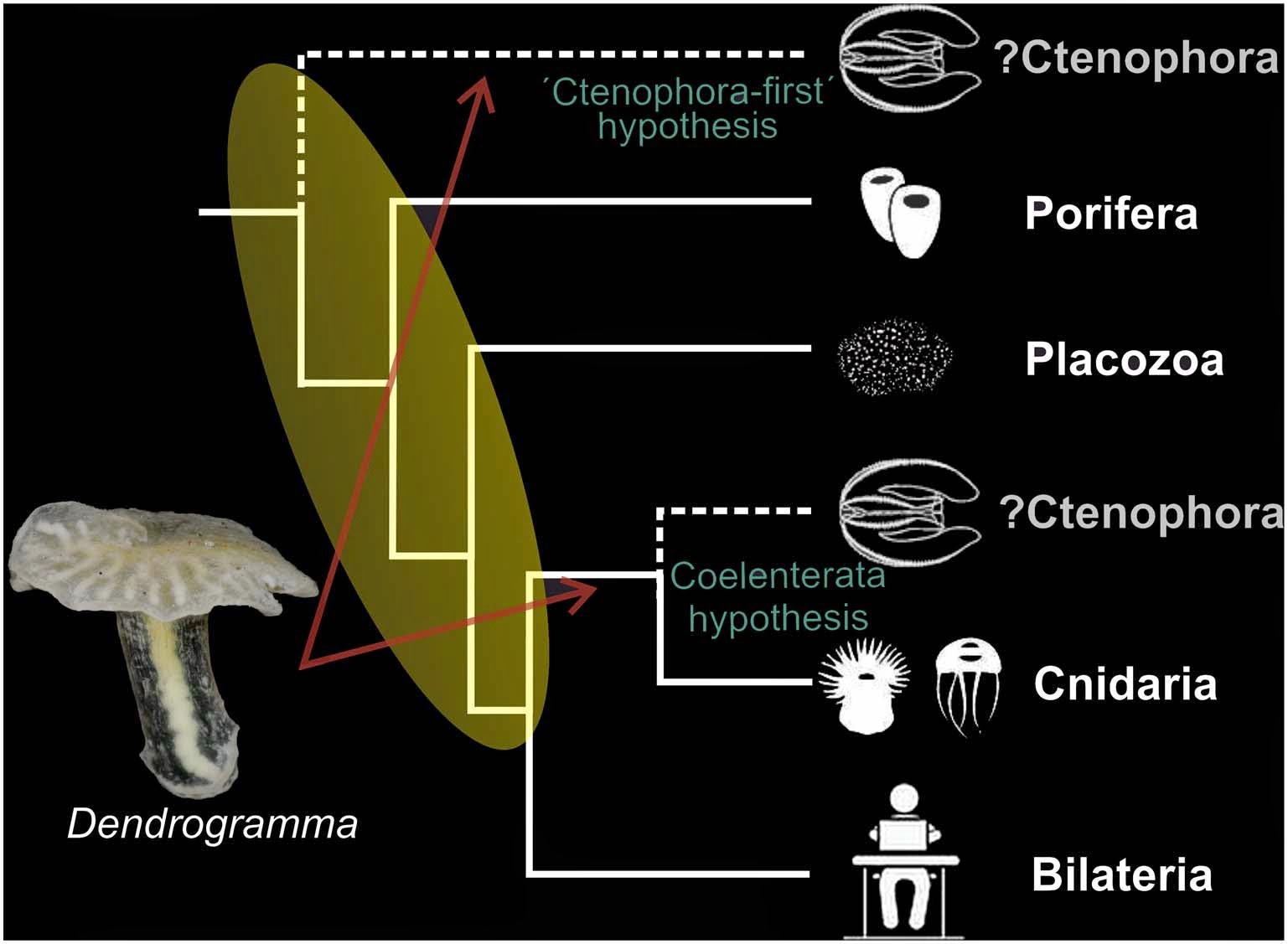

Possible positions of Dendrogramma in a simplified phylogeny showing the deepest splits

in the metazoan Tree of Life. The position of Ctenophora is controversial so

two possibilities have been shown with dashed lines, one as sister group to the

remaining metazoans (the ‘Ctenophora-first’ hypothesis), and one as sister

group to Cnidaria (Coelenterata hypothesis). Just et al. suggest that Dendrogramma most

likely is related to Ctenophora and/Cnidaria (red arrows) due to general

similarities in body organisation. However, depending on the position of Ctenophora

and on whether certain aspects of Dendrogramma

(e.g., mesoglea and gastrovascular system) are ancestral for Metazoa or

modified, Dendrogramma can be

positioned in a variety of ways below Bilateria (yellow oval). Just et al. (2014).

Dendrogramma also shows a resemblance to some fossils from the Ediacaran fauna,

notably Albumares brunsae, Anfesta stankovskii, and Rugoconites. These fossils

share a similar morphology to Dendrogramma,

with a disc-shaped body containing a system of branching canals similar to the

gastrovascular system of Dendrogramma,

although all are considerably larger. In addition Albumaresbrunsae and Anfestastankovskii

have tri-lobed mouths, similar to those seen in Dendrogramma discoides. The branching system of Rugoconites tenuirugosus appears initially branch three times, while

that of Dendrogramma always branches

twice (giving its branches a ‘Y’ shape), but Just et al. estimate that if Dendrogramma

was also preserved in the same position, then it would also appear to have an

initial three-way branch, suggesting that this could also be an artefact in Rugoconites tenuirugosus.

(1)Albumares brunsae,

(2) Anfesta stankovskii, (3) Rugoconites enigmaticus. Just et al. (2014).

This means that if the phylogenetic position of Dendrogramma can be resolved, then this can be used to infer that

of Albumares, Anfesta, and Rugoconiteste, providing

further insight into the relationships between Ediacaran and modern faunas, and

helping to resolve the Vendazoan hypothesis (since if Dendrogramma can be shown to be related to a modern animal group,

then presumably the Ediacaran fossils that resemble it also do so).

See also…

The fossils of the Ediacaran Period record the first widespread

macrofossils in the rock-record. Many of these fossils do not appear to belong

to any modern group, but instead are thought to belong to an extinct taxa

(sometimes known as ‘Vendobionts’), which may-or-may-not be related to modern

Animals, though some fossils have been linked to Sponges (a group which...

Most modern animal groups appear abruptly at, or very shortly after, the

beginning of the Cambrian period, 542 million years ago. The Cambrian

starts abruptly with a layer of small shelly fossils that are hard to

assign to any group, which are then replaced abruptly by fossils

belonging to more familiar groups; arthropods, molluscs, brachiopods,

etc., which then persist...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.