Palaeontological studies of the Arctic during the Early-to-Middle

Eocene have revealed a world in which the ice-free Arctic Ocean was surrounded

by lush warm-temperate rainforests, inhabited by creatures such as Alligators,

Turtles and Hippo-like Mammals. The fauna of the Arctic Ocean itself is less

well known, however, though Shark’s teeth and Fish otoliths (mineralized

tissues from the ears of Fish and some marine invertebrates) from Ellesmere

Island have been since at least the 1970s, and from Banks Island since the 1980s.

In a paper published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology on 4

November 2014, Aspen Padilla of the University of Colorado Museum of NaturalHistory at the University of Colorado at Boulder and the Chemeketa CommunityCollege Library, Jaelyn Eberle of the University of Colorado Museum of Natural

History and the Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Colorado

at Boulder, Michael Gottfried of the Department of Geological Sciences and

Museum at Michigan State University, Arthur Sweet of the Geological Survey of

Canada (Calgary) at Natural Resources Canada and Howard Hutchison of the Universityof California Museum of Paleontology describe the results of a study in which

sediments from the Eureka Sound Formation collected from near the Muskox and

Eames rivers, within the boundaries of Aulavik National Park on Banks Island

were sieved to yield Sharks teeth. These sediments are judged to be

Early-to-Middle Eocene in age, spanning the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum.

Sharks produce large numbers of teeth throughout their lives, regularly

shedding and replacing teeth. This means that they produce very large numbers

of tooth fossils that can be used in biostratigraphy (dating rocks by their

fossil content) and palaeoenvironemental reconstructions, even though Shark

macrofossils (body fossils) are very rare.

Map of Arctic Canada showing locations of Eocene shark

localities within Aulavik National Park, northern Banks Island, NWT (inset). L McConnaughey

in Padilla et al. (2014).

The first Shark taxa recorded is Striatolamia macrota,

a form of Sand Tiger Shark previously recorded from Eocene sediments in a

variety of locations. This is one of the most abundant species present, with

thousands of isolated teeth found.

Teeth of Striatolamia macrotafrom

northern Banks Island.(A–C) an anterior tooth in lingual (A), labial (B), and

profile (C) views; (D, E) lower lateral tooth in lingual (D) and labial (E)

views; (F, G) upperlateral tooth in lingual (F) and labial (G) views; (H, I)

posterior tooth in lingual (H) and labial (I) views. Padilla et al. (2014).

The second species recorded is an unnamed species of Carcharias (anther Sand Tiger Shark),

referred to as Carcharias sp. A. This

species is also represented by thousands of isolated teeth. Members of the

genus Carcharias are still extant

today, and inhabit warm-temperate and tropical seas.

Teeth of Carcharias sp.

A from northern Banks Island. (A–C) anterior tooth in lingual (A), labial (B),

and profile (C) views; (D, E)lateral tooth in lingual (D) and labial (E) views

(A–E share a scale); (F, G) lateral tooth in lingual (F) and labial (G) views; (H,

I) posterior tooth in lingual (H) and labial (I) views. Padilla et al. (2014).

The third species recorded is a second species of Carcharias, referred to a Carcharias sp. B. Specimens assigned to

species B have week striations, which are absent in species A, and the largest

teeth of species B are notably smaller than the largest teeth of species A.

This species is also represented by thousands of isolated teeth.

Teeth of Carcharias

sp. B from northern Banks Island. (A–C) Anterior tooth in lingual (A), labial

(B), and profile (C) views; (D, E) lateral tooth in lingual (D) and labial (E) views. Padilla

et al. (2014).

The fourth species recorded is Odontaspis winkleri,

a fourth species of Sand Tiger Shark, though in this case only represented by

two isolated teeth. The genus Odontaspis first

appeared in the Late Cretaceous, and is still extant, with a modern species

found in tropical and warm temperate waters in the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific

Oceans and the Mediterranean Sea.

Lower symphysealtooth of Odontaspis winkleri in lingual(A), labial (B), and profile (C) views.

Padilla et al. (2014).

The fifth species recorded is Physogaleus secundus,

an extinct relative of Tiger and Sharpnose Sharks (but not Sand Tiger Sharks,

which are not closely related to Tiger Sharks). This species is recorded from

22 isolated teeth; this being the furthest north the genus Physogaleus has been recorded.

Anterolateral tooth of Physogaleus secundus in lingual (D) and labial (E)views. Padilla et al. (2014).

The seventh species recorded is a single tooth also placed in the

genus Physogaleus, but recorded as

cf. Physogaleus americanus; that is to

say Padilla et al. are confident that

the tooth come from a Shark of the genus Physogaleus,

and that they most closely resemble the tooth of Physogaleus americanus, but that they are not completely confident

of this. Physogaleus americanus is

known from the Late Palaeocene and Early Eocene of Mississippi, though the

Banks island tooth is considerably larger than the largest teeth recorded from

Mississippi, at 6.1 mm, compared to an average of 3 mm for the Mississippi

teeth.

Lateral toothof Physogaleus

cf. Physogaleus americanus in lingual

(H)and labial (I) views. Padilla et al. (2014).

The eighth species recorded is a single tooth from an unknown

Myliobatid Ray, Myliobatis sp., the

genus that includes modern Eagle Rays, and which is now found in warm-temperate

to tropical waters across the globe.

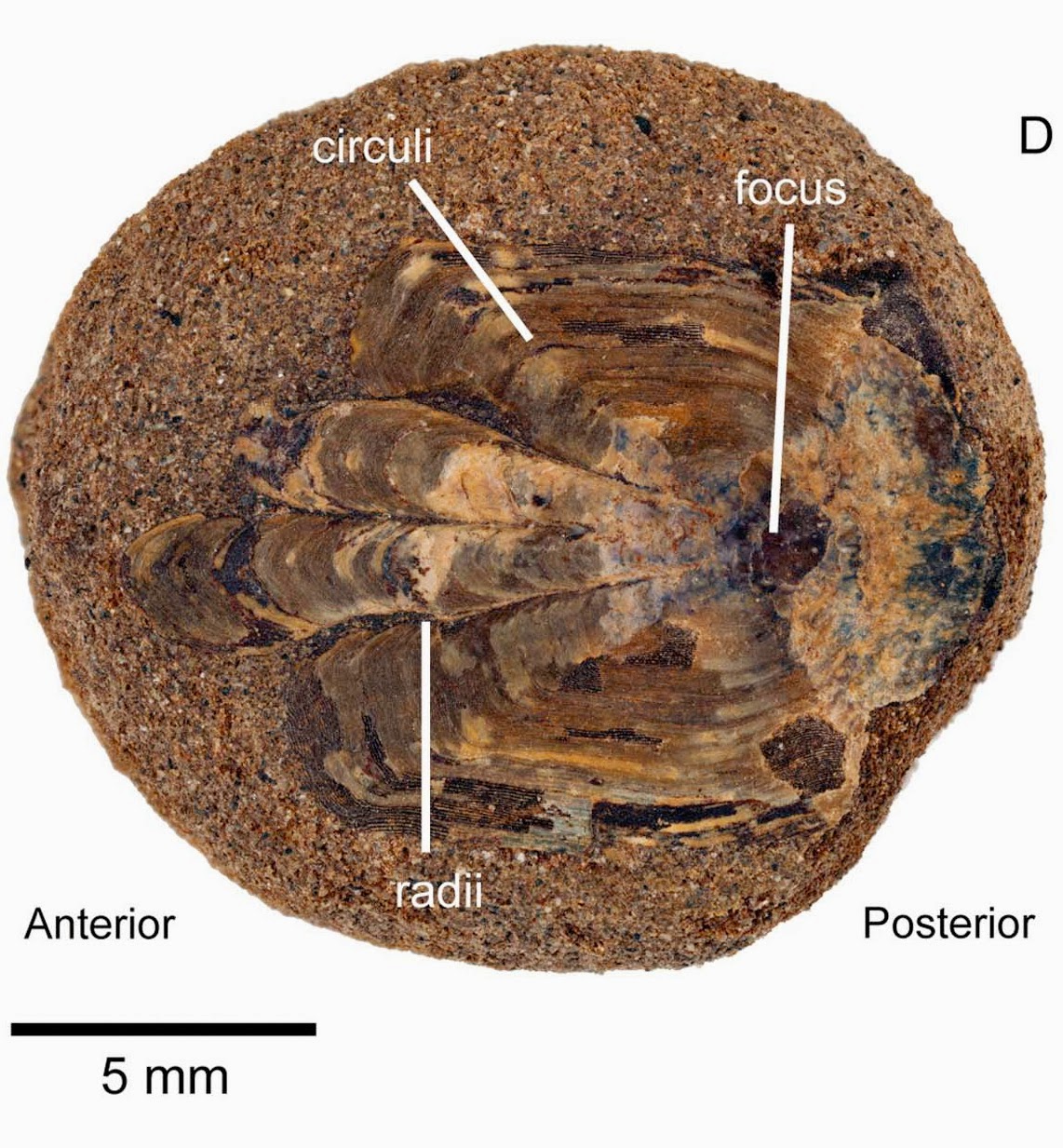

Upper median tooth of Myliobatis sp. in occlusal (J), side (K), and basal (L) views. Padilla

et al. (2014).

The Shark faunal assemblage from the Early Eocene of Banks Island

conforms to the predicted climatic model, being made up entirely of species

found in warm temperate, or warmer, waters today. However it is unusually poor

in species for such an assemblage, with just a tiny handful of specimens that

do not come from the most abundant three species. This is typical of modern

polar species assemblages, which tend to be dominated by one or two abundant

species, but unusual in warmer waters, where a more diverse community is

typical.

There does not seem to be any good reason why a warm Arctic fauna

would be dominated by a low number of species in the way modern cold arctic

faunas are. Instead Padilla et al. propose

an alternative hypothesis for this low species diversity, which is independent

of the latitude of the site. Modern Sand Tiger Sharks often enter brackish (low

salinity) estuarine and delta waters to feed, as to Eagle Rays, but most other

Sharks prefer fully saline waters. The deposits on Banks Island appear

consistent with bar formations around the outer margin of a delta, an

environment where fresh and saline water often mix, producing a low salinity

environment, and Padilla et al. suggest

that this may be the cause of the low species diversity seen there.

See also…

The Giant Shark, Carcharocles megalodon,

is one of the more charismatic creatures of the recent fossil record, a

relative of modern Mackerel Sharks that is thought to have been able to reach

about 18 m in length, known from the Middle Miocene to the end of the Pliocene,

with some claims of the species persisting into the Pleistocene. It is

interpreted to have had a life-style similar to the modern Great White Shark,

which preys...

Whale Sharks (Rhincodon typus) are the largest extant Shark

species, and indeed the largest living Fish...

The remains of a variety of non-marine Vertebrates have been recovered

from Ellesmere and Axel Heiberg Islands in the eastern Canadian High

Arctic from the 1970s onwards. These vertebrate assemblages date

from early – middle Eocene (53–50 million years ago), when the islands

were close to their current positions within the...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.