Egypt lacks any notable silver deposits of its own, and silver objects were rare during the Old Kingdom, with the metal not becoming a commonly imported commodity until the early Middle Kingdom, about 1900 BC. Silver objects dating to the Old Kingdom are therefore extremely rare, and generally associated with high status royal burials. One of the most notable groups of silver objects is a collection of bracelets from the tomb of Queen Hetepheres, the wife of the Pharoah Sneferu, who was the first ruler of the Forth Dynasty and reigned from approximately 2613 to 2589 BC, and mother to Pharoah Khufu, who built the Great Pyramd at Giza.

The origin of silver from this period is uncertain. It could potentially have come from local sources which have since been lost; the Ancient Egyptians are known to have mined gold extensively, and seams of silver in gold-bearing rocks are not unusual. Alternatively, silver could have been imported from one of the cities of what is now Syria, most likely Byblos on the southern coast, which Egypt had been trading with since at least the Naqada IIIA1 Period (about 3320 BC), although cities further north were also traded with, with Elba having been added to the trade network by the end of the Old Kingdom, about 2300 BC.

The tomb of Queen Hetepheres at Giza was uncovered in 1925, by a joint expedition of Harvard University and the Museum of Fine Arts. This tomb had been undisturbed till this point, and contained a trove of artefacts including gilded furniture, gold vessels and jewellery. Among this jewellery was the remains of a wooden box containing twenty silver 'deben' rings (a 'deben' was a unit of weight, although the value of this appears to have changed over time). The rings were in a variable state when uncovered (unlike gold, silver will corrode over time), and the whole collection was sent to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In 1947 two intact rings from this collection, along with a number of fragments of silver from rings which had disintegrated, was gifted by the Egyptian Museum to the Museum of Fine Arts.

When worn, these rings would have been bracelets, with five worn on each limb. They are made from thin sheets of silver folded into a cresent shape, so that there is a cavity on the inner side, and inlaid with turquoise, lapis lazuli and carnelian, in a style which clearly establishes their Egyptian origin. A metallurgical analysis of the metal was carried out in the 1920s, finding it to be 90.1% silver, 8.9% gold, and 1.0% copper, but the distribution of the gold was uneven, giving the bracelets yellowish patches. Since that time no further metalogical examination of the rings has taken place.

In a paper published in the Joutnal of Archaeological Science: Reports on 1 May 2023, Karin Sowada of the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University, Richard Newman of the Museum of Fine Arts, Francis Albarède of the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon, Gillan Davis of the Australian Catholic University, Michele Derrick, also of the Museum of Fine Arts, Timothy Murphy of the School of Natural Sciences at Macquarie University, and of Newspec Pty Ltd, and Damian Gore, also of Newspec Pty Ltd, present an updated metallurgical analysis of the silver from the bracelets of Queen Hetepheres, and discuss the implications of their results for the likely origin of this metal.

(A) Bracelets in the burial chamber of

Tomb G 7000X as discovered by George

Reisner in 1925 (Photographer: Mustapha

Abu el-Hamd, August 25 1926) (B) Bracelets

in restored frame, Cairo JE 53271–3

(Photographer: Mohammedani Ibrahim,

August 11 1929) (C) A bracelet (right) in the

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MFA 47.1700.

The bracelet on the left is an electrotype

reproduction made in 1947. Sowada et al. (2023).

The bracelets donated to the Museum of Fine Arts were not available for study, but Sowada et al. were able to access the fragmentary material given to the museum at the same time. These samples were analysed using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy to analyse their elemental composition. Furthermore, trace amounts of lead recovered from the sample were anlalysed using Multicollector Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry, in order to determine their isotopic composition, which is strongly linked to geogrsphical origin.

(A) Bag B1 of corroded bracelet fragments in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MFA 47.1702. MFA 47.1702 B1P4 shown second from left, centre. (B) Detail of MFA 47.1702 B1P4 (C)–(D) Metallic fragment recto (left) and verso (right) MFA 47.1702 B2P1. Sowada et al. (2023).

Sowada et al. found that the bulk sample of metal fragments was 98% silver, with 1% gold, 0.4% copper, and 0.04% lead. Patches of corrosion are dominated by silver chloride. Some other elements appear to have accumulated on the surface of the sample, notably calcium, but also iron, probably in the form of iron oxide grains. Examined under an a scanning electron microscope, fragments of the silver seen in section showed a pattern of dark and light layers typical of metal which has been worked heavily while cold, something often seen in Old Kingdom copper samples. Mapping of the elements in these profile sections suggested that the material was in fact about 90% silver and about 10% gold.

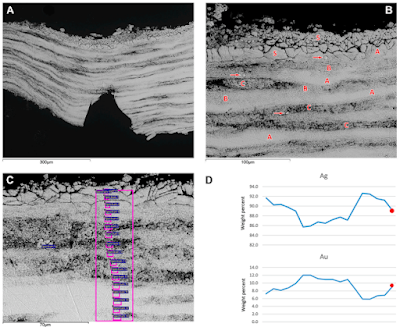

(A) Back-scattered electron image of

part of the polished cross section from MFA

47.1702 B2P1 (B) Detail from image A at

higher magnification, showing the metal

structure to consist of elongated islands of

uncorroded solver metal ('A') intercalated with

a more porous matrix ('B') transitioning to

an open framework of corroded metal ('C'). (C) Concentrations of silver and gold in

small regions (purple outlines) were determined and plotted in (D). The plots begin at

the top of the area shown in (C) and end at

the bottom. The final data point is for the

larger rectangular area and can be considered the average for this part of the sample

(about 89% silver and 9% gold). Note that gold has

higher concentrations and silver lower in the

more heavily corroded areas (data points in

the middle of the plots). Sowada et al. (2023).

The lead within the samples was found to have a lead²⁰⁶/lead²⁰⁴ ratio of 18.8816. This was compared to a database containing the isotopic rations of lead ores from 7000 locations between Iran and the Atlantic Ocean. This analysis susgests that the silver is most likely to have come from the Cyclades Islands, in the Aegean Sea to the southeast of the Greek mainland, and that the second most likely point of origin is the Lavrion mines of Attica.

Map of the north-east Mediterranean and western Asia, showing potential silver sources. The lead isotope composition of a sample from

MFA 47.1702 B2P1 is compared with the compositions of nearly 7000 samples of galena (white dots) distributed from the Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean from

the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon database. The distance (colour bar to the right) allows 128 galena samples with the closest lead isotope compositions relative to

MFA 47.1702 B2P1 to be retained. Unlikely sources can be ignored. A black symbol colour indicates a high probability of provenance with the greatest density of ‘hits’

coming from Seriphos, Anafi, and Kea-Kithnos in the Cyclades, and to a lesser degree Lavrion. Red and orange symbols indicate less probable sources (Anatolia,

Macedonia). The symbol sizes have been slightly jittered and enlarged to increase visibility of the less probable points. Sowada et al. (2023).

Silver is known to have been mined in the Aegean region from the very beginning of the Bronze Age, and to have increasingly been traded around the Mediterranean as time passed; nevertheless, finding it as far afield as Egypt during the early Fourth Dynasty is surprising. Silver is known to have been imported to the Old Kingdom, with records dating to the reign of the Pharoah Sneferu mentioning the metal as an import, although not where it was imported from. The earliest records which do mention a source date to the late Sixth Dynasty (around 2300 BC), and record silver being imported from Byblos, in southern Lebanon. At the same time, records from Elba, in northern Lebanon, report silver being exported from that city to Egypt.

Heterpheres was the wife of Sneferu, who ruled 300 years before the Sixth Dynasty records were made, at a time when there is no direct evidence for trade between Egypt and Lebanon. A jug believed to have come from Cilicia in the Taurus Region of southern Anatolia is known from a slightly later tomb, suggesting that the Egyptians were trading this far north. This has been taken as evidence that Egypt could have traded silver from the cities of Lebanon, it is also known that silver from the Aegean was being traded in Anatolia by this time.

See also...