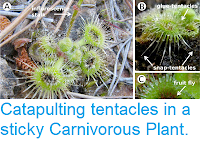

Sundews, Droseraceae, are a highly successful group of Carnivorous Plants found around the globe. Like other forms of Carnivorous Plants, they can grow on very poor soils by supplementing their nutritional intake by feeding on animals, generally Insects or other small Invertebrates. Sundews capture their prey using specialised leave, which are covered in tentacles, each of which is tipped with a blob of sticky glue, that adheres to the prey animal preventing it from escaping. As the animal struggles it is likely to encounter multiple tentacles, all of which will stick to it until it becomes wrapped and immobilised, enabling the plant to digest it. The Pygmy Sundews, Drosera spp., are the largest single genus of Carnivorous Plants known, with over 250 described species, over 110 of which come from Australia. The genus has a Southern Hemisphere distribution, being found in arid regions of Brazil, South Africa and Australia. These plants are distinguished by small leaves and orange flowers.

In a paper published in the journal Phytotaxa on 6 April 2018, Alastair Robinson of Southbank in Victoria, Australia, Adam Cross of the Centre for Mine Site Restoration of the Department of Environment and Agriculture of Western Australia, Manfred Meisterl of Vienna in Austria, and Andreas Fleischmann of the Botanische Staatssammlung München, describe a new species of Pygmy Sundew from Western Australia.

The new species is named Drosera albonotata, meaning ‘white marked’ in reference to the white markings on the petals of this species. The new species is a perennial herb forming rosettes 0.8-2.5 cm in diameter, with 6-18 active leaves. The leaf rosettes start out flat to the soil, but as the plant grows each season’s growth overlays the previous, so that in some plants it sits on top of a 4 cm layer of withered leaves. Flowers are born in September and October, on a stem that rises 3.3-14.2 cm above the plant. Each stem can bear up to 15 orange, five-petaled flowers, 16-25 cm in diameter, each petal having two white markings at its base, that form a collar around the centre of the flower.

The new species is named Drosera albonotata, meaning ‘white marked’ in reference to the white markings on the petals of this species. The new species is a perennial herb forming rosettes 0.8-2.5 cm in diameter, with 6-18 active leaves. The leaf rosettes start out flat to the soil, but as the plant grows each season’s growth overlays the previous, so that in some plants it sits on top of a 4 cm layer of withered leaves. Flowers are born in September and October, on a stem that rises 3.3-14.2 cm above the plant. Each stem can bear up to 15 orange, five-petaled flowers, 16-25 cm in diameter, each petal having two white markings at its base, that form a collar around the centre of the flower.

Living plants photographed in situ, showing left a flowering plant, and right a mature rosette. Alistair Robinson in Robinson et al. (2018).

See also...

The plants were initially found growing in the Wandoo National Park, and subsequently found in the shires of Northam, York and Quairading, and possibly Cunderdin, Tammin and Kellerberrin (there was some difficulty in establishing the full range of the plants, as many were growing in agricultural areas, and the study period overlapped with the Wheat harvest), all within the western Wheatbelt region of Western Australia. They favoured woodland on ridges and low rises, generally on gravelly slopes and pale yellow to brown sandy clay-loam soils with a moderate to dense shrub understorey. Several observations were made of a Scarab Beetle of the genus Liparetrus visiting the flowers of Drosera albonotata and emerging covered in pollen. This is unsurprising, as Beetles of this genus are known to pollinate several Sundew species. The species is known from less than ten locations, each with about 25-150 individuals, and all within an area of less than 2000 km², and the species is clearly at risk from expanding agriculture in the region. As such Drosera albonotata is assessed to be Vulnerable under the terms ofthe

International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species.

A pollinator of Drosera albonotata, identified as a Melolonthid (Scarabaeidae) possibly in the genus Liparetrus. Alistair Robinson in Robinson et al. (2018).

See also...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

+sp.jpg)

+sp.jpg)