Many, if not all, of the world's biodiversity hotspots are under threats from Human activities such as farming, overgrazing, mining, bush burning, hunting, poaching, and timber harvesting. Tropical forests in particular are under threat from habitat disturbance and modification, leading many Animals which live there to modify their ecology and behaviour. It has been estimated that over 90% of the habitats utilised by Great Apes in Africa will be moderately-to-highly impacted by Human activity by 2030.

The Eastern Lowland Gorilla, or Grauer’s Gorilla, Gorilla beringei graueri, is a Critically Endangered subspecies of Gorilla found in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, with a population known to have fallen to about 250 adult individuals in the 1990s, and thought to have suffered a drop in population size since this time of between 60% and 90% (which if correct, would indicate a current population of between 25and 150 adult individuals surviving in the wild. Like all Gorillas within the Democratic Republic of Congo, they are threatened by civil conflict within the country, roads being cut through the forest, forest clearance for agriculture, new refugee camps and other Human settlements springing up, mining, both legal and illegal, poaching for bushmeat and other purposes, and exposure to Human diseases. Grauer's Gorillas are considered particularly sensitive to even low levels of hunting, due to their slow reproductive cycle, with females first giving birth at about 10 years of age, then producing about one baby every four years.

Attempts to protect both the Grauer's Gorillas and the forests in which they dwell have taken place amidst a series of civil conflicts and a fragile economic situation, resulting in high levels of poaching and habitat clearance. Many people in the region are dependent on subsistence agriculture, resulting in areas of the forest being constantly cleared to provide access to fertile soil. Furthermore, most people living in rural areas in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo are dependent on wood gathered in the forest for heating and cooking. The area is further threatened by the effects of global warming, leading to droughts, floods, and wildfires raging through the region.

In a paper published in the journal Diversity on 16 April 2024, Kahindo Tulizo Consolee and Xiaofeng Luan of the School of Ecology and Nature Conservation at Beijing Forestry University, and Li Cong of the School of Landscape and Architecture at Beijing Forestry University, present a review of the anthropogenic pressures threatening the survival of Grauer’s Gorillas and their habitats, particularly in the vicinity of the Maiko National Park, and consider ways in which the local population can be made more aware of the threars faced by the species and engaged with the conservation process.

Much of the pressure on the forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo comes as a result of wealth distribution within the communities of the country, and the wider world. Human behaviour can lead to environmental degradation, through the expansion of agricultural production areas, overgrazing, deforestation, leading to the destruction of ecosystems, water shortages, and contamination of water sources, all of which is further exacerbated by global climate change. Rural populations close to the forests are dependent on them for a wide range of products and services, including wild Animal products, honey and timber, and traditional medicine, as well as land for subsistence agriculture. Urban populations also depent upon the forests to provide economic resources such as meat, palm oil, coffee, soybeans, and chocolate, which are produced on large farms and plantations on the forest edges or on areas of cleared forest.

Consolee et al. note that people living closest to the forests tend to use forest resources in traditional ways which tend to be sustainable, urban dwellers, while further away, are responsible for the extraction of greater amounts of resources such as timber, charcoal, and food, a pattern which has also been observed in other countries with rain forests, such as Madagascar, Indonesia, and Brazil. In all of these countries forests are threatened by agricultural activities and farm expansion, illegal logging, mining, hunting, poaching, and local and international trade demands for food and non-food commodities such as tropical timber. Illegal mining, for gemstones and rare metals is a significant cause of habitat destruction, deforestation, and pollution of surface and groundwater. It also serves as a driver of Human migration into forests, leading to the building of roads and settlements, deforestation, poaching, and pollution.

The expansion of agriculture remains a threat to forests across the globe. Land clearance to provide land for plantation farming and livestock ranching is a major cause of natural forest loss, with plantations providing only a very limited proportion of the serviced offered by natural forests. In addition, the management of plantation farms requires the construction of new road networks into forests, facilitating Human access deeper into the forest, and leading to further degradation of uncleared areas.

The Democratic Republic of Congo is home to two thirds of the Congo Basin Tropical Forest, the second largest area of tropical forests in the world, after the Amazon Basin. This is about 2.4 million km² of forest, or about 18% of the world's total tropical forests. The Congo Basin is home to about 400 species of Mammals and over 1000 species of Birds, as well as over 10 000 species of Plants, about 3000 of which are endemic to the basin. Mammals found only in the Congo Basin include Graur's Gorillas, as well as the Eastern Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, and the Bonobo, Pan pansiscus, both of which have been classified as Endangered. This forest is not just a vast area of incredible biodiversity, but also a crucial carbon sink playing a vital role in managing the Earth's climate, yet the economic pressure to develop the basin is placing the forest under threat across nearly its entire extent.

The Maiko National Park covers an area of 10 885 km² in the eastern Democratic of Congo. It has an altitude of between 605 and 1033 m above sealevel, and is covered by lowland tropical forest. Animals endemic to the park include Graur's Gorillas, Okapi, Africa Forest Elephants, and Congo Peafowl. As well as the forests, the Oso and Lindi rivers provide significant aquatic ecosystems. The Plants and Animals of this forest provide the main source of food, traditional medicine, and income for the communities which surround it.

Many of the pressures which threaten this forest come from outside the immediate area, including rising populations in urban areas, a scarcity of land, demand for firewood and charcoal, as well as plantation-grown forest products, and conflicts which drive people from other areas into Maiko and other protected areas.

Maiko National Park. Consolee et al. (2024).

About 32% of the Democratic Republic of Congo's forest cover is thought to have been lost, much of it from mountainous areas, making it one of the world's most threatened ecosystems and a global conservation priority. Human population growth within the country occurs mostly within towns and cities within the lowland forests, presenting a challenge for conservation efforts in these areas, where many species have already been declared extinct or are considered to be very close to it. Without urgent action, it is thought that the Graur's Gorilla will become extinct within the next few decades.

Schematic representation of the effects of anthropogenic activities on natural resources, forests, and Gorillas habitats in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Consolee et al. (2024).

Graur's Gorillas are thought to be more threatened by Human activities than any other Primate. Large tracts of the forests that form their home have been destroyed, and the remaining forest is highly fragmented. The Human population of the area has risen rapidly in recent decades, with significant impact on all natural resources, as well as the loss of habitat to agriculture, urbanization, and pollution. Such disturbances are particularly threatening to large, slow breeding species such as Gorillas. To make matters worse, as habitat is lost to forest fragmentation, there are less opportunities for Gorilla-Gorilla interactions, leading to a loss of social skills and a lower mating success. This has led to a sharp decline in both the number of sexually mature adult Graur's Gorillas, and an equal drop in the area of forest inhabited by the species. This includes the Gorillas in protected areas such as the Maiko National Park. Thus, if Graur's Gorrilas are to survive, there needs to be a concerted effort to understand both the current status of the species, and to develop effective communication and conservation methods among all stakeholders in the conservation process.

The attitude towards conservation of local communities depends not just on the people of those communities, but also upon the efforts of conservation project managers to involve those people in a positive way. Most people in the Democratic Republic of Congo show little interest in conservation efforts or the protection of the environment, probably due to the ongoing conflict situation in the area, and presence of numerous armed groups. Furthermore, many people in the area report feeling that parks promote the looting of natural resources, cultural wealth, and traditional knowledge. Use of forest resources is often abusive and irrational, which fuels conflict between Humans and Gorillas.

More than 20 million people in the Congo Basin are directly reliant on forest resources for subsistence. The savannahs and forests of the Congo Basin provide food, water, and resources to both the people and Animals of the basin, as well as playing a key role in global carbon storage. The Human population of the basin has lived in harmony with the natural environment for millennia, however, in the modern world this relationship has largely broken down.

The major driver of habitat loss within the range of Graur's Gorillas is the destruction of forests to provide agricultural land, both for subsistance farming and commercial plantations. Overgrazing of livestock, illegal mining, road building, and the harvesting of trees for timber and charcoal all add to the fragmentation of the forest. As well as directly fragmenting the forests, road building encourages hunting and the establishment of new communities (principally by refugees from the regions many conflicts) deeper into the forests, leading to further forest clearance, and making previously inaccessible areas available to poachers, who can threaten both wildlife and local communities.

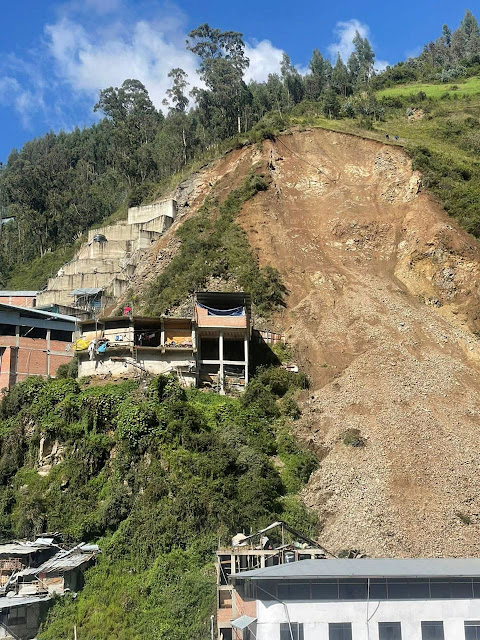

Illegal mining site in the Maiko National Park. Consolee et al. (2024).

The pressures faced by the Gorillas and the forests they live in are ultimately driven by economic factors, and the distribution of wealth within the Democratic Republic of Congo. A very large number of people are dependent on subsistence agriculture, as well as other extractive practices such as charcoal and timber harvesting. However, a greater proportion of the forest's resources are probably consumed by the urban middle classes, who rely on farms, plantations, and forest extraction industries to provide them with commodities such as meat, palm oil, coffee, soybeans, chocolate, timber, and fuel. Plantations and commercial forestry projects opened in response to these demands lead to the construction of new roads, further opening the forest to other Human activities. All the pressures on the forests are predicted to grow over the next 20-30 years, due to a rising Human population combined with virtually non-existent social development, hight unemployment, low incomes, and a lack of affordable alternative energy sources. More than 90% of households in the Democratic Republic of Congo are engaged in agriculture, and the population is rising by 2-3% per year, driving the demand for forest land to be cleared, as well as for forestry products such as timber. The felling of trees releases large amounts of carbon dioxide, fuelling global warming which affects the whole world, including the Congo Basin. Globally, deforestation is thought to be responsible for about 18-25% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.

Forest encroachment and deforestation; anthropogenic pressure to Gorillas and Gorillas’ habitat. Consolee et al. (2024).

The numerous conflicts which have plagued the Democratic Republic of Congo have had a significant negative impact on Graur's Gorillas, and other wildlife, by driving poaching and habitat loss. The hunting, killing, capturing, and consuming Gorillas are all in theory illegal, but this cannot be enforced in any meaningful way in parts of the country dominated by armed groups reliant on artisanal mining, where a scarcity of farmed Animals has led to bushmeat, including Gorilla, becoming the major source of protein. Armed groups living within the forest provide a direct threat not just to Gorillas but to the staff of national parks in the Democratic Republic of Congo. For example, an attack by an armed rebel group on 24 April 2020 killed twelve rangers, a driver, and four civilians working in conservation roles in the Virungu National Park, also part of the home range of the Graur's Gorilla. This was by no means an isolated event, with more than 200 park employees being killed in clashes with poachers and rebel groups while on duty in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the past thirty years, about 10% of the total number of employees. These conflicts have also effectively ended tourism to the region, removing a major potential source of income for the parks.

Spent remains of gun bullet cartridges within the Maiko National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo. Consolee et al. (2024).

The forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo have become home to large numbers of illegal miners, extracting valuable minerals such as gold, diamonds, and cobalt. These miners are another significant source of deforestation and habitat loss, and are heavily reliant on bushmeat for food, presenting a threat to all Animals within the forests. Furthermore, pollution from illegal mines has had a huge impact on aquatic water systems, with rivers such as the Oso and Lindi in the Maiko National Park to have lost most of their Fish. Interviews with illegal miners suggest that they prize the meat of Gorillas, and find these Animals easy to hunt with modern firearms, as well as a source of large amounts of meat per individual. In addition to the meat value of adult Gorillas, infants have a value on the black market, where they are traded as exotic pets or exhibits for unscrupulous zoos. In addition to the direct decline in numbers caused by these events, violent encounters with Humans disrupts the natural behaviour of Gorillas, reducing their ability to survive.

An increased Human presence in the forests can also cause Gorillas to lose their fear of Humans, leading them into further conflict. Human-habituated Gorillas may raid farmland for crops, possibly even attacking people working in fields, or gathering wood in forests. They may also fail to avoid poachers, with lethal consequences.

The consumption of bushmeat is a cultural norm for rural communities in the Democratic Republic of Congo, as in many other parts of Africa. A rising population in and around the forests where Gorillas dwell places a higher pressure on all species hunted there, including the Gorillas themselves, which are hunted for meat for both subsistence and to trade. A variety of guns and snares are used to hunt, and spent shotgun cartridges are often found in the forest. It has been estimated that about 5% of the Gorilla population of the Maiko National Park is killed by poachers each year. This is particularly devestating due to the slow breeding rate of Gorillas.

Historically, Gorillas have been hunted for meat, as well as for their heads, hands, and feet, which have been used in traditional medicine and sold to westerners as souveniers. Live Gorillas have been sold to zoos, researchers, and people who wanted exotic pets. The capturing of infant Gorillas for trade is particularly damaging to the species, as adults in a group will typically fight to the death to protect their young, with the effect that the capture of one infant typically requires at least two adults to be killed. Furthermore, the mortality rate for juvenile Gorillas in captivity is about 80%, so that each live Gorilla that reaches a zoo probably represents 15 Gorillas killed in the wild.

In addition to the direct threats caused by Human encroachment, the forests of the Congo Basin are threatened by anthropogenic global warming. It is estimated that this alone could destroy 75% of the remaining Gorilla habitat by 2050. Warming brings with it not just higher temperatures, but also an increased risk of extreme weather events such as flooding or droughts, which in turn bring a higher risk of forest fires. The loss and fragmentation of habitat in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, where almost all of the montane forests favoured by Gorillas have vanished, means that Gorillas have to range over wider areas to find food resources, something which is hampered by flooding. Higher temperatures lead to Gorillas needing to drink more water; if this is combined with a drought event then the ability of Gorillas to forage widely is restricted, as they need to stay close to a more limited number of sources of drinking water. Furthermore, the low breeding rate and limited genetic variability of Gorillas means that they have little hope of evolving to cope with a changing climate.

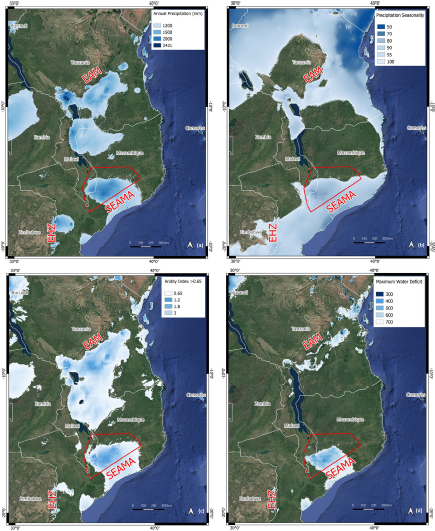

Within the Maiko National Park rising temperatures have been associated with a prolonged dry season and lower rainfall, leading to a reduced seasonal moisture within the forests. This has led to a degradation of the forest vegetation, negatively affecting the Gorillas behaviour.

Zoonotic diseases are infections capable of jumping between Human and Animal hosts. Such diseases are an increasing threat to global healthcare systems, as Humans encroach further into former wild spaces and encounter new pathogens, for example the COVID-19 pandemic is thought to have originated from the consumption of the meat of wild Animals. Zoonotic diseases present a particular challenge for Great Apes, which can catch a range of Human pathogens. Gorilla populations which frequently interact with Humans are known to suffer a higher rate of respiratory infections than Gorillas which do not, frequently showing symptoms such as sneezing, coughing, running nose, and open-mouth breathing. Increased bushmeat hunting in the forests of the Congo basin has led to an increased rate of infections jumping between Animals and Humans, most notably in the form of frequent and deadly epidemics of Ebola Virus Disease, which can have devastating effects upon Gorillas as well as Humans.

There are is no established system of domestic water treatment and supply in the area around the Maiko National Park. This means that local people are reliant on river water for drinking and other domestic purposes, leading to frequent outbreaks of waterborne diseases, including Cholera, Typhoid, Bilharzia, and Amoebiasis. Gorillas, which are reliant on the same sources of water, are therefore potentially being exposed to all of these pathogens.

The most common cause of serious illness and death in Gorillas are respiratory infections, which they appear to be poorly adapted to cope with; infections which cause very minor symptoms in Humans have been known to kill Gorillas. Gorillas are known to be prone to Ebola, Common Cold Virus, Pneumonia, Smallpox, Chickenpox, Tuberculosis, Measles, Rubella, and Yellow Fever, and appear to be able to catch a wide range of respiratory diseases from Humans.

As elsewhere around the globe, in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo the lowest-income households were the most adversely effected by the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to an upsurge in bushmeat hunting, with species such as Gorillas targeted for both meat and use in traditional medicinal practices. The pandemic also led to a withdrawal of both government workers and international researchers from forests and parks, and the vanishing of tourism-generated income, all of which tend to act at least as a partial buffer against Gorilla poaching. It is likely that Gorillas were adversely affected by both hunting and disease transmission during this interval, although data on this was not collected.

Recent Ebola outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo are known to have affected Gorillas as well as Humans. The disease is considered particularly lethal in Humans, killing about 80% of people who contract it, but is even more dangerous for Gorillas, with a mortality rate of between 90% and 95%. It has been estimated that the 2018-20 Ebola outbreak killed about a third of the surviving Gorillas in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The threat presented by Ebola to Gorillas is also considered a problem for the populations in Uganda and Rwanda.

Monkeypox Virus is another zoonotic infection spread by respiratory droplets or direct contact with infected individuals, which was first recorded in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1996-97. The disease, which is again known to be able to infect Gorillas, re-emerged in multiple countries in May 2022, with over 250 cases reported around the globe.

Although the picture for the future of Grauer's Gorillas that Consolee et al. paint is particularly bleak, they do present some suggestions to reduce the threats faced by the species in and around the Maiko National Park.

Good governance could potentially reduce poverty in the communities around the park, as well as increasing food security and enabling the population to contribute to managing the forests and the wildlife that lives in them. If local communities become beneficiaries of conservation efforts, then they are likely to become far more invested in the success of those projects. This would require village-level engagement becoming part of ecology and conservation projects. Consolee et al. note that projects imposed upon communities from outside, no matter how viable they appear on paper, are seldom productive if they do not inspire the participation of local communities. The involvement of local communities in conservation projects also enables the robust monitoring of the success of those projects from ground-level, something which is almost impossible when projects are directed from remote, overseas locations. Making local communities stakeholding beneficiaries can motivate them to maintain the biodiversity of the Gorilla's habitat, improving the viability of projects through the input of local knowledge.

Successful management of national parks requires significant political and economic support. Properly funded national parks can offer employment to local people, as well as building infrastructure which benefits nearby communities. If the Maiko National Park can be properly funded then local communities could be encouraged to take a more active role in the conservation of Grauer's Gorillas and the forests they need to survive. Thus, the action plan for the park needs to involve plans to work with the government to improve services and infrastructure for communities in the region. If the strategic plan includes steps to provide local communities with alternative fuels for cooking, then they would become less dependent on harvesting wood from the forests. Working with local communities would potentially identify other ways in which the park could provide useful infrastructure to those communities. An education campaign would also help local people to understand the impacts of deforestation and poaching, further involving them as stakeholders in the project. Consolee et al., however, emphasise that all of this must be built upon a foundation of poverty-alleviation in communities around the park, improve agricultural productivity, and provide people with sufficient financial needs that the consideration of biodiversity as an asset becomes an option.

The protection of local cultures, languages, land-use practices, and knowledge of ecosystems, should be a key part of conservation programs aimed at protecting forests and wild Primates, if these projects are to have a chance of success. The definition of the term 'poaching' used by park authorities needs to be examined closely, to keep a clear definition between subsistence activities and large-scale extractive practices. Defining subsistence practices which have long formed a part of local community practice as 'poaching' is likely to alienate those communities, whereas incorporating the knowledge upon which such practices are based into conservation plans may improve the prospects of projects. Consolee et al. believe that the co-production of knowledge with local communities should be a dynamic process, able to draw on local knowledge to help to respond to changing circumstances. Conservationists should pay attention to local taboos, which are often built around indigenous ways of protecting the environment and managing scarce resources. Such practices can potentially align with Gorilla-conservation projects, building a conservation framework in which the values of local peoples are built into the parks governance, building trust in the wider goals of conservationists. Anthropologists can play a useful role in helping organizations to become more aware of local knowledge and practices, and sometimes to help local peoples to develop specific taboos around protected species. If Gorillas could become protected by both government policy and local taboo then government policy would be seen as upholding local values and vice versa, enabling conservationists to work with local traditional and other local leaders, to establish the cultural and biodiversity value of sites which should be prioritised for conservation, enabling conservationists and local populations to develop common goals.

The role of bridging organizations and traditional knowledge in co-management of natural resources and forest conservation. Consolee et al. (2024).

Natural habitats offer services to both the local and global community which are far more valuable than destructive consumption, both in financial and non-financial terms. Despite this, forests in areas such as the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo continue to be lost, at least in part because of a lack of meaningful involvement of local communities in conservation initiatives. The development of a global market in carbon sinks has the potential to provide finances for projects such as the Maiko National Park, which have global value in terms of atmospheric services as well as being crucial to the survival of species such as the Gruaer's Gorilla. Carbon credits could potentially be used to plant forests of indigenous trees, rather than commercially useful alien species, maintaining the biodiversity of the region.

Thus, the current degradation of nature could potentially be followed by a Green Anthropocene, with a world still dominated by Human influences, but with conservation and the preservation of biodiversity being driving motivations in Human activity. Consolee et al. envisage a brighter future for biodiversity as being possible if people can learn to live with nature and prioritise ecological preservation and restoration, even though the consequences of current Human actions on the natural world may take centuries or even millennia to manifest. Achieving such a Green Anthropocene will require extra-ordinary efforts, and the development of much more productive agricultural methods for countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, to reduce the Human need to encroach upon forests and clear bush. This will require great effort by both Congolese and global institutions, significant international co-operation, and targeted investment in conservation projects over the next 20-50 years, the timeline which will also determine whether the Graur's Gorilla will survive.

The first step in creating such a future should be the involvement of local peoples in the management of projects such as the Maiko National Park, creating systems of co-management between local peoples and governments which share responsibility for the future of the park. Such co-operation should make local people feel empowered, and give them a sense that the projects are run in an equitable and just way. Power-sharing is inherently more equitable than top-down directives issued by governments, and produces decisions and policies which reflect local values and culture, as well as giving the local population the power to manage their environment. Promoting the preservation of Grauer's Gorillas and their environment will require the engagement of local people through educatation programs and the promotion of an awareness of the benefits of a functioning ecosystem, and the development of ways of managing the environment which take into account the concerns of the people who live there.

Well-managed ecotourism projects can be a driver of community engagement with conservation projects, bringing immediate financial benefits to the local community which can be clearlry associated with the presence of charismatic species such as Gorillas. Gorilla-related ecotourism projects already operate in Rwanda and Uganda, providing a model which could be adapted to the Maiko National Park. If done well, ecotourism projects use wildlife and natural resources sparingly, and the visitors attracted by such projects tend to have a commitment to self-improvement and ecological sustainability, likely to financially contribute to supporting a sustainable local economy.

The survival of the Grauer's Gorilla requires the preservation of the tropical forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo, which are currently being lost rapidly to Human encroachment. These forests are essential for the continued survival of a wide range of other wildlife, as well as acting as a water-store and buffer against erosion. They are also one of the world's major carbon sinks, helping to stabilize the global climate. At the moment, the forests of the Congo Basin, including those in protected areas such as the Maiko National Park, are threatened by agricultural expansion, urbanization, logging, mining, poaching, and the extraction of wood for fuel.

Protecting the forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo is likely to require significant international effort, but also needs to reflect the needs and cultural values of the people that live in the area. A more organised approach to studying the wildlife of forests such as those of the Congo basin will also improve our ability to predict and react to the emergence of zoonotic diseases with the potential to become global pandemics.

See also...

%20(1)%20(1).png)

%20(1)%20(1).png)