Lophophorates are animals which feed using a filter called a

lophophore, which comprises a number of setae covered tentacles, to extract

food from water. The group includes the shelled Brachiopods, the worm-like

Phoronids, the minute Entoprocts and colonial Bryozoans, and has been shown by

molecular and embryonic evidence to be related to the Molluscs and Annelids.

Within the Lophophorates the Phoronids and Brachiopods are thought to be

closely related, with some studied suggesting that the Phoronids should be

regarded as a shell-less subgroup of the Brachiopods.

In a paper published in the journal Scientific Reports on 15 May

2014, a group of scientists led by Zhi-Fei Zhang of the Early Life Institute, StateKey Laboratory of Continental Dynamics and Department of Geology at Northwest University and the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology of the

Chinese Academy of Sciences, describe a Lophophorate Animal from the Early

Cambrian Heilinpu Formation of the Haikou, Erjie, Shankou and Chengjiang areas,

around Kunming, in Yunnan Province, China; deposits known as the ‘ChengjiangLagerstätte’

or ‘Chengjiang Fauna’ due to the large number of exceptionally well preserved

fossils found there.

The species is described from over 700 specimens, and is given the

name Yuganotheca elegans, where ‘Yuganotheca’ means ‘Yugan’s shell’ in

honour of the late Yugan Jin for his work on the Brachiopods of the Chengjiang

Fauna, and ‘elegans’ means

‘beautiful’ (though this is not specifically explained).

Yuganotheca elegans has a pair of muscular ‘valves’ which encase its lophophore, similar

to the shell valves of Brachiopods, but lacking a mineralized shell and

possessing a fringe of setae around their matgins. Instead these valves are

covered in agglutinated sand particles, a strategy unknown in Brachiopods, but

common in Phoronids, which often use agglutinated particles to cover the upper

part of their trunks, which must be projected above the sediment when feeding.

The arrangement of the lophophore tentacles is different from that seen in

Brachiopods, and appears to have been capable of projecting into passing

currants, whereas Brachiopods open and shut their shells to pump water through

the lophophore. Behind the valves is a muscular collar, then a straight conical

tube-like trunk and a long flexible pedicle (tail).

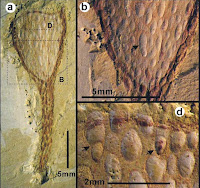

Yuganotheca elegans from the early Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte, Yunnan, China.

Arrows point to the borders between the upper pair of valves (Avs), median

collar (Mc), lower conical tube (Pc), and pedicle (Pe); M = mouth; Lo =

lophophore; Va = visceral area; Dg = the terminal pedicle bulb with adhered

grains; Se = setae; Ten = tentacles. (a), Holotype, compare to (b). (c–d),part

and counterpart; note the lophophore imprint in (d). (e), compare to (d). (f) complete

individual with well-developed pedicle. Zhang et al. (2014).

Some of the specimens show a dark u-shaped structure within the

collar area, which Zhang et al. interpret

as a an alimentary canal originating from a mouth within the lophophore

structure and terminating at an anus on the lateral side of the body, an arrangement

similar to that seen in Phoronids.

Yuganotheca elegans from the early Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte, Yunnan, China.

Arrows point to the borders between the anterior pair of valves, median collar,

lower conical tube, and (in 2a, b, d) pedicle; all scale bars are 5 mm. (a)

Nearly complete specimen. (b) Specimen showing the central lumen (Pc) and the

terminal bulb (Dg) of the pedicle. (c–d) Specimens showing the oblique growth

fila of the lower cone and gut remains; note U-shaped lineation interpreted as

the digestive tract marked by left (Lg) and right (Rg) parts; note the putative

location of mouth (M) and probable anus (?A). (e) Specimen showing well-preserved

ventral mantle canals. (f) Interior dorsal valve. Zhang et al. (2014).

The close relationship between Brachiopods and Phoronids suggested

by molecular data has suggested that Brachiopods arose from a Phoronid-like

ancestor, although how a shelled Brachiopod (even a vermiform one such as a

Lingulid, which have worm-like bodies and phosphatic shells covering only their

exposed foreparts) arose from a Phoronid-like animal lacking the bivalved

structure which defines Brachiopods has been hard to assess. Yuganotheca elegans appears to bridge this

gap, possessing a pair unmineralized valves surrounding the lophophore

structure, combined with a mixture of other traits seen in Phoronids and

Brachiopods, such as a Phoronid-like U-shaped gut and agglutinated covering and

a Lingulid-like pedicle anchoring it to the sediment.

Artistic reconstruction of Yuganotheca elegans with inferred semi-infaunal life position. Dong-Jing Fu

in Zhang et al. (2015).

The valves of Yuganotheca elegans show

clear affinities with those of Brachiopods, while the elongate pedicle is

similar to the tails of Phoronids and Lingulid Brachiopods, but the rigid

conical section of the body, which is interpreted as having been used to hold

the valves and lophophore above the sediment, is not found in either group.

However it is reminiscent of phosphatic tubes produced by some Tommotiids, an

enigmatic group of Cambrian fossils, suggesting that these may be relatives of

the Phoronid/Brachiopod group.

See also…

The Lophotrochozoa are a diverse group of Invertebrate animals indicated

to have a common ancestry by genetic analysis. The group includes the

Annelida, Mollusca, Bryozoa, Cycliophora, Brachiopoda, Entoprocta and

Phoronida. Within this group several groups are united by the presence

of a crown of tentacles (the Lophophore) surrounding the mouth, which

continuously opens and shuts while...

Brachiopods (or Lampshells) superficially resemble Bivalve Molluscs,

though they are not closely related. They were abundant in the seas of

the Palaeozoic, often dominating benthic faunas, but today are

comparatively rare, and seldom seem outside the...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.