The Uğurlu archaeological site is located on the western end of the island of Gökçeada in the northern Aegean Sea. The site is a settlement recording a series of important transitions from the pre-pottery Neolithic through to the Early Bronze Age, covering a period of about 2500 years, from approximately 6800 to 4300 BC, and including the advent of Animal husbandry, agriculture, the use of ceramics, copper, and bronze.

One of the important features of this site is that it covers the transition from the Neolithic to the Chalcolithic, between about 5500 and 4900 BC, one of the few sites in western Anatolia and the eastern Aegean Islands to do so. As well as seeing the introduction of copper, this interval included reorganisations in the way settlements were laid out and how buildings were constructed, new forms of pottery, and the development of a subsistence economy.

During this period, the settlement at Uğurlu appears to have been divided into two portions; a communal building with a large courtyard to the west, and a group of multi-roomed buildings interpreted as dwellings to the east. A series of pits were excavated to the northwest of this area, partially surrounding the communal building. Most of these pits are between 10 and 90 cm in depth, and are lined with a green clay. These pits contained a variety of materials, including fragments of pottery, Animal bones, clay and marble figurines, bone and flint tools, fragments of shell ornaments (bracelets, rings, etc.), and stone axes. All the pits had been infilled, then covered with large stones.

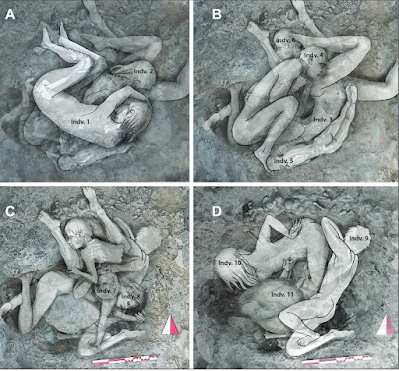

Four of these pits contained Human remains. Pit 25 contained 7 fragments of Human bone, and pits 29 and 104 contained smaller amounts of material. However, the final pit, 188, is significantly larger, and contains eleven sets of more-or-less complete Human remains.

In a paper published in the journal Documenta Praehistorica on 26 September 2022, Başak Boz of the Department of Archaeology at Trakya University, discusses the way in which these bodies were placed into the pit, and the possible motivations of the people who placed them there.

The location of Uğurlu on the island of Gökçeada in the Aegean. Boz (2022).

Radiocarbon dates were obtained from two bones within the pit, one from the skeleton at the bottom of the pit, interpreted as having been the first skeleton deposited, and one from a Human bone in the uppermost layer of material. The skeleton at the bottom of the pit was dated to 5389-5310 BC, while the upper bone was dated to 5363-5302 BC, making both roughly contemporary with the communal building, the earliest stage of which has been dated to between 5300 and 4300 BC.

The distribution of the pits around the communal building. Boz (2022).

The pit is roughly 1 m in diameter and 2 m deep, making it one of the largest pits from this phase of the occupation. Its floor and walls have been lined with a yellowish green clay plaster. Eleven individual sets of Human remains were placed within the pit, with numerous stones between them; the upper 60-80 cm of the pit comprised an infill of stones above the last body, with a marker stone being placed above this.

The pit also contained a great deal of other material, including two broken grinding stones, a large amount of fragmentary pottery, three pieces of red ochre, some beads, a worked bone, and portions of two Calf skeletons as well as numerous other Animal bone fragments. One large rock within the middle of the pit was covered by a layer of sterile ash roughly 30 cm in diameter and 1.5 cm thick.

The approximate ages and sexes of the skeletons were determined by examination of the pelvis and skull, the pubic symphyses, and tooth wear. The individuals were estimated to be aged from about three years old, to mature adults, aged in their 30s or 40s.

Most of the bones of the individuals in the pit were broken, in some cases severely crushed. However, there is no sign of any of these injuries having been caused before death, and no signs of other pathologies due to ill heath or injury on the skeletons.

Fresh bone breaks (indicated by arrows) related withthe stones between the skeletons. Nejat Yücel in Boz (2022).

The skeleton at the base of the pit (Individual 11) is that of a child aged 5-6 years, laying on top of a layer of apparently randomly distributed stones covering the pit floor. The skeleton is lying on its right side, with the left arm and leg extended towards the south, and the rest of the body in a flexed position. This skeleton was covered by a layer of rocks and Animal bones, including the two broken grinding stones and partial Calf skeletons. One of the grinding stones covered the child's head.

(A) The first individual at the bottom of the pit, (B) stones and Animal bones over the skeleton. Boz (2022).

Above this skeleton another five sets of remains were deposited apparently randomly on top of one-another, with some stones between. All of these skeletons are intact, but their postures imply they were thrown into the pit, rather than being placed carefully. The first of these (Individual 10) is a middle-aged woman, face down with her body in a perpendicular position against the wall of the pit, with the hips and legs about 50 cm higher than the head, and her arms twisted behind her back in a position suggesting they were tied. The two largest stones in the pit were thrown in on top of this woman, with one of them apparently completely crushing her head. The larger of these stones, weighing about 80 kg and in the middle of the pit, was then covered with the layer of sterile ash.

Skeleton of a female (Individual 10) with her hands at her back. Boz (2022).

A further four bodies were then deposited into the pit on top of Individual 10, again in an apparently careless way. These being Individual 9, a child of about twelve years and indeterminate sex, Individual 8, another adult woman in her thirties or forties, Individual 7, and Individual 6, another child of about 10-12 years.

Illustration of the position of individuals in relation to each other. (A) Is the top view of the pit with skeletons and (D)is the lowest level. Only the bodies are shown here to avoid further crowding with the stones in between the bodies. Begona Rodriquez in Boz (2022).

One of these, the mature male, Individual 7, was lying on his back with his legs against the side of the pit. His arms were tightly bent at the shoulders, with his hands on his shoulders, and his legs tightly folded at the knees, suggesting that he also might have been bound before being dumped into the pit.

Illustration of an adult male (Individual 7), the arm and hand positions suggesting binding. Begona Rodriquez in Boz (2022).

Another of these bodies, the male child, Individual 6, was separated into two parts at the waist, with the articulated upper body lying directly on the abdomen of Individual 7, with no stones between them, while the lower part of the body is disarticulated and scattered within the pit.

The next skeleton, Individual 4, is a young adult male (probably in his twenties), apparently laid intentionally on his side, with his legs folded up into his abdomen, and his arms folded against his chest, with his hands on his shoulders. This individual is also thought likely to have been tied in this position, or possibly tightly wrapped in a perishable material, since it is an unnatural position for a body to naturally rest in.

The tightly flexed position of individual 4. Boz (2022).

Another four individuals above this burial also appeared to have been dumped into the pit, again mixed with a large number of loose rocks, although the limbs of some of these individuals are interwound, suggesting that the infill came after the bodies were deposited. These final skeletons are; Individual 5, a young child, roughly three-to-four years old, Individual 3, an adolescent girl, about eighteen years of age, and Individuals 1 and 2, two more middle aged women, in their thirties or forties. These final burials appear more disturbed than the lower skeletons, with several having portions missing; Individual 1 is missing her right ulna, Individual 3 her right fibula, and Individual 5 the bones of the right lower leg.

Intertwined extremities of different individuals with no fill between them indicating simultaneous disposal of the bodies. Boz (2022).

The burial at Uğurlu is unusual in nature, with eleven individuals jammed into a pit 1 m in diameter and 2 m deep, along with a large quantity of rocks. Fitting this many bodies into such a small hole cannot have been easy, and may have been done over some period of time, giving each body a chance to decay, and thereby take up less space, before the next body was added. This would have required the pit to be covered by some sort of a lid between depositions, with the rocky infill being added at the end of the process. This fits somewhat with the circumstances of the burial, with little material between the bodies, with the exception of the child at the bottom, who appears to have been covered over before the other bodies were added, and is supported by some skeletal elements which appear to have shifted downwards with regards to the bodies from which they originated, notably the pelvis of Individual 7.

Illustration of the bodies in order in the pit. Begona Rodriquez in Boz (2022).

An alternative possibility is that this was a secondary burial, with the bodies having been stored elsewhere until they were all deposited in the pit together in a single event. This would help to explain the disarticulated nature of the lower half of the child, Individual 6, who could have been in an advanced state of decomposition when deposited. However, the condition of the upper body of the same individual presents a problem for this hypothesis, as even the small bones of the fingers remain articulated, incompatible with such a state of decomposition. Some ancient cultures are known to have practised ritual defleshing or dismemberment between primary and secondary burials, which might explain such a mixed state of articulation, but the absence of cut marks on any bones argues against this. The missing limb portions of the uppermost bodies could also offer evidence for this hypothesis, but the upper part of the pit has also been entered by several Animal burrows, which offer a better explanation for these missing bones, and the fact that only the skeletons at the top of the pit are affected.

Thus neither of these scenarios quite fits with the available evidence, although it remains likely that the bodies do represent two separate events, the deposition and covering of the first child's body, followed by the later deposition of the remaining ten bodies.

The Late Neolithic-Early Chalcolithic period was one of considerable cultural diversity across the region that encompasses the Balkan Peninsula, Greece, Thrace, the Aegean Islands, and Anatolia, with a wide range of burial customs known. However, the customs of western Anatolia, the region closest to the island of Gökçeada, are poorly represented for this interval.

At the Barcın Höyük VI site in the Marmara region of northwest Anatolia, which was in use between about 6600 and 5900 BC, adult individuals were buried in courtyards, while children were buried in abandoned houses. At Aktopraklık, also in the Marmara region, a Late Neolithic site dated to between 6400 and 6235, all individuals are buried in a flexed position beneath the floors of houses. The first cemeteries appear in the Marmara region in the Chalcolithic at Aktopraklık C and Ilıpınar X/IX.

Further west, infant burials within settlements are known from Ulucak in the seventh millennium BC, but little other information is available.

In the sixth millennium BC, Neolithic burials in the Balkan region also generally occur within settlements, with both flexed and supine burial positions used, although these are generally at different sites. Here, supine burials were the norm in the Mesolithic, but the flexed burials represent a new phenomenon, possibly originating in the Near East. Fragmented burials are also quite known from the Balkans, with parts of bodies having apparently been removed, or even replaced with other objects. Also found in the Balkans are ditch burials, in which individuals were buried away from settlements, and pit burials of both individual and multiple bodies, sometimes after cremation; these pit burials are also known from Greece and Central Europe.

Between about 5400 and 4500 BC distinct cemeteries, outside the bounds of settlements, developed in the Balkans, which has been suggested as evidence of a changing relationship between the dead and the living, although the variety of different ways of dealing with the dead seen before seems to persist in the cemeteries.

Of particular similarity to the Uğurlu sites are the pit cemeteries of the eastern Balkans, particularly Bulgaria, where pits of a variety of shapes were dug outside of settlements, and filled with a mixture of debris, including grinding stones and Animal bones, before being capped off with a stone cairn. Only a minority of these pits have produced Human remains, but those that do often produce multiple sets of remains. These pits have been suggested as a site of sacrifice, in which offerings were placed, and sometimes burned.

No burials from earlier phases at Uğurlu, which may indicate burials taking place away from the settlement as seen elsewhere in the Balkans and Anatolia. The first pits appear at the site during phase IV (roughly 5500-5300 BC), when three pits were dug, which do contain some fragmentary Human material, along with other items. However, the main bout of pit-digging activity occurred during Phase III (5300-4900 BC), during which interval 37 pits were dug, filled with material, and then marked, suggesting they were of some significance to the people of the settlement. Much of the material within the pits is broken and fragmentary, which is in keeping with the tradition of braking and sharing of items, including bodies, which were passed around within communities before burial, during the Neolithic of the Balkans and Near East.

Pit 188 was in use between approximately 5389 and 5310 BC, and appears similar in construction to the other pits at Uğurlu, with the exception that it was significantly larger, and contained multiple sets of Human remains.

It is possible that the sudden deposition of a large number of bodies into a single pit, most of them in a somewhat haphazard way, was a reaction to an epidemic, an event which might provoke the living to dispose of the dead with more haste than was usual within their society. Such an event would be expected to produce dead members of all age groups and both sexes, with a high proportion of children and the elderly. None of the remains from Pit 188 show any sign of disease-associated pathologies, however, pathologies affecting the bones would not be expected with an acute plague-like infection, being more typical of chronic conditions which take their time to kill their victims. However, it is unclear why some of the bodies would have been bound if they were victims of a plague that people wished to dispose of quickly, nor why artefacts would have been placed within the grave with them.

The haphazard nature in which the bodies were placed within the pit, and the fact that some of the victims were bound, raises another possibility, that they were the victims of Human sacrifice, or possibly a local group killed off by invaders. Both warfare and Human sacrifice are known to have been prevalent in the Neolithic and Chalcolithic, with potential massacre sites recorded at Halberstadt (5600-4900 BC) and Talheim (about 5000 BC) in Germany, Asparn-Schlets (about 5000 BC) in Austria, Potočani (about 4200 BC) in Croatia, and Els Traocks (about 5300 BC) in the Spanish Pyrenees.

Sites associated with warfare tend to have a predominance of young adult and middle aged males, and generally include broken and discarded weapons. The Uğurlu pit contains only one young adult and one middle aged male, along with four middle aged women, one adolescent girl, and four children, an unlikely composition for a war grave. Furthermore, no weapons, broken or otherwise, are present within the pit, nor are there any signs of the sort of injuries expected at a battle site, such as fractures or blunt force traumas. Some fractures are observable, but these appear to have been caused by stones being dropped onto the bodies within the pit, with the stones still being in place at the time of excavation (although it is impossible to tell whether the victims were alive or dead at the time when these injuries were inflicted).

This leaves the possibility of some form of organised Human sacrifice. Human sacrifice can be difficult to identify in the archaeological record, as it is generally impossible to identify why people were killed, but if it is an established part of a culture, then it is likely that people will repeatedly be killed in the same way, probably at regular intervals over an extended period of time. In such cases the victims are typically placed in identical positions, and accompanied by similar grave goods.

Uğurlu Pit 188 is located in a courtyard along with a series of other pits. It differs from the other pits in size, and the presence of multiple Human skeletons, but otherwise is of similar construction, lined with similar clay, contains similar material (made artefacts, Animal bones), has a similar rocky infill, and is marked with a similar capstone. This does suggest that the pits had some sort of a repeated ritual purpose, but the Human contents of Pit 188 are unusual.

Grave goods can be indicative of ritual sacrifices, but those from Pit 188 are ambivalent. The pit contains portions of two Calves, and two broken grinding stones, as well as several beads, three pieces of red ochre, and a stone covered with ash, but none of these is directly associated with any of the skeletons, and no signs of personal ornamentation are present.

Another possibility, which has been suggested for other sites, is that some of the bodies were sacrificed to accompany a high status individual into the afterlife. The Bergheim Pit in France, dated to about 4000 BC, contains a large number of severed arms, followed by the body of an older male with a severed arm who had apparently died a violent death, then a series of intact skeletons buried in a haphazard way, which has been interpreted as evidence of sacrifices made to accompany the death of an important individual. At Didenheim in the Alsace region of France, burials where individuals placed in specific positions accompanied by individuals in haphazard positions have been interpreted in the same way.

Human sacrifice might be expected to leave distinctive trauma marks on a body, which cannot be observed at Uğurlu. However, there are plenty of ways of killing a Human which do not mark the skeleton (the only remains present at Uğurlu), so this is somewhat inconclusive.

The presence of a carefully placed body, Individual 4, within a large number of haphazardly placed individuals, accompanied by some possible ritual materials (ash, red ochre), may indicate that the other bodies were sacrificial victims placed within the pit to accompany this high-status individual.

Pit 188 at Uğurlu represents the first true burial at this site (some older pits contained fragmentary Human remains), potentially shedding light on the ritual activities and belief system of the people living at the site. However, interpreting this burial site is particularly challenging, given the haphazard way in which the majority of the bodies were deposited, the fact that some (but not all) appear to have been bound before deposition, and one body having been buried in two parts. The context of the pit, surrounded by other pits of apparent ritual importance, makes it likely that this burial had symbolic importance. One possibility is that the majority of those within the pit were killed to accompany an important person, Individual 4, who alone was apparently buried in a pre-planned way. This in turn implies that these people had started to develop a social hierarchy, with some individuals meriting different treatment in death to others.

Similar accompanying burials are known to have been practised in central and eastern Europe by about 4500 BC, moving westward and southward over the next millennium. If the example at Uğurlu does represent the same phenomenon, then it pushes the origin of this custom back to about 5300 BC, and demonstrates an origin in the Aegean/Anatolian region, where it has not previously been observed.

See also...