Fossilised Dinosaur integument has been known for nearly 150 years, yet it is only recently that it has been considered more than a simple impression (trace fossil) of the original skin surface. Although feathers and filamentary protofeathers of Avian and non-Avian Theropods have received considerable attention, particularly in the past two decades, squamous (scaly) skin is more widespread and was probably plesiomorphic (the original state) in Dinosaurs. Significant advances in our understanding of the preservation and structure of squamous skin have been achieved with the use of synchrotron radiation techniques, and it is now generally accepted that labile tissues, such as skin and muscle, can preserve and remain intact millions of years after the death of the organism. Hadrosaur skin is relatively common in the fossil record, but few studies have investigated either its composition or the possible determining factors behind its preservation.

In a

paper published in the journal

PeerJ on 16 October 2019,

Mauricio Barbi of the

Department of Physics at the

University of Regina,

Phil Bell of the

School of Environmental and Rural Science at the

University of New England,

Federico Fanti of the

Dipartimento di Scienze Biologiche, Geologiche e Ambientali and the

Museo Geologico Giovanni Capellini at the

Università di Bologna, James Dynes of

Canadian Light Source Inc. at the

University of Saskatchewan, Anezka Kolaceke, also of the Department of Physics at the University of Regina,

Josef Buttigieg of the

Department of Biology at the University of Regina,

Ian Coulson of the

Department of Geology at the University of Regina, and

Philip Currie of

Biological Sciences at the

University of Alberta, describe the results of a study of a study of a sample of three-dimensionally preserved squamous skin from a Hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Wapiti Formation, discovered near the city of Grande Prairie in Alberta, Canada.

The Wapati Formation of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin outcrops across parts of northwestern Alberta and northeastern British Colombia. It is a series of sandstones, siltstones, mudstones and related deposits laid down in a broad floodplain associated with a meandering river system between the Campanian (83.6-72.1 million years ago) and the Palaeocene (66-56 million years ago). The Cretaceous portion of this formation has yielded a variety of Dinosaur fossils, though most of the fossil-producing exposures are in inaccessible locations, limiting palaeontological efforts.

The speciemen examined by Barbi et al., UALVP 53290, is an incomplete Hadrosaur recovered from the Red Willow Falls locality, less than one kilometre to the east of the Alberta-British Columbia border. In this area, late Campanian deposits of the Wapiti Formation have been dated at 72.58 million years old and consist of repeating fining-upward sequences of crevasse-splays, muddy and organic-rich overbank deposits, and minor sandy channel fills. Sandstones are primarily formed by poorly-sorted quartz, feldspar, and carbonate clasts, commonly presenting a carbonatic cement. Thin and discontinuous altered volcanic ash beds are found at the top of fining-upward successions, where they are locally interbedded with coal lenses. The specimen comprises an incomplete articulated-to-associated Hadrosaurid skeleton with most of the thoracic region, forelimb and pelvic elements. Parts of the tail likely continue into the cliff but could not be recovered owing to the precipitous nature of the outcrop. The only cranial element found, an incomplete jugal (cheekbone), indicates Hadrosaurine affinities, though the material is not sufficient to diagnose the specimen to species level. Another Hadrosaur specimen recovered from nearby could be assigned to Edmontosaurus regalis, and Barbi et al. consider it likely that UALVP 53290 belongs to the same species.

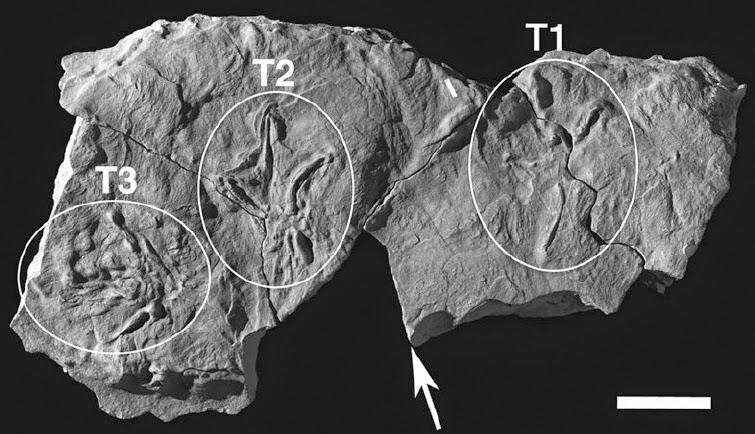

Sheets of in situ and partially displaced fossilised integument were found close to the forelimbs of UALVP 53290, and occur in two types: as a 2 mm thick black rind preserving the three-dimensionality of the epidermal scales, and as low-relief structures covered in a thin, oxide-rich patina. The skin samples examined by Barbi et al. were slightly displaced relative to their true life position but are presumed to have come from the dorsal (anterior) surface of the forearm. The integument is composed of large (10 mm), hexagonal basement scales identical to scales on the upper surface of the forearm in other Edmontosaurus specimens.

UALVP 53290. (A) quarry map showing location of preserved integument (indicated by numerals) shown in (B) and (C). Dark grey regions are freshwater bivalves. (B) Higher magnification of (1) showing dark-coloured polygonal scales . (C) Detail of (2) showing cluster areas associated with the forearm integument. (D) Detail of dark scales in oblique view showing sampling locations for spectromicroscopy: samples were collected with a microtome from (i) the outer surface of the epidermal scale to produce a light-coloured powder, and (ii) from a cross section of the scale that penetrated into the pale underlying sedimentary matrix to produce a dark-coloured powder. Scale bar in (A) is 10 cm. Scale bars in (B) (D) are 1 cm. Abbreviations: Dv, dorsal vertebra; H, humerus; Mc, metacarpal; Os, ossified tendon; Pu, pubis; R, rib; Ra, radius; Sc, scapula; Th, Theropod tibia; Ul, ulna. Line drawing by Phil Bell. Barbi et al. (2019).

Scanning Electron Microscope studies of a 20 μm thick cross section of the Hadrosaur skin were conducted with the intention of investigating possible markers that could discriminate the skin from the sedimentary matrix, and (b) identify potential regions for the presence of organic contents.. The thin section covers the first 2 cm of the sample starting from the outer surface of the scales To better understand the morphology of the Hadrosaur skin, histological skin samples were prepared for a Chicken, Gallus gallus domesticus, a Saltwater Crocodile, Crocodylus porosus, and a Rat, Rattus norvenicus, and compared with the Hadrosaur skin.

Optical microscopy of histological samples of the skin from three extant representatives (Gallus, Crocodylus, Rattus) reveals a thin but characteristically multi-layered epidermis and a deeper, thicker dermis. The outermost epidermal layer corresponds to the stratum corneum, a keratinous layer that aids in protection of the internal organs (including the underlying epidermal and dermal layers) from desiccation. The stratum corneum, which is composed of stratified layers of β -keratin, is the thickest component of the epidermis in Crocodylus owing to the presence of keratinised scales. As a result of this cornified layer, the epidermis is also the thickest in Crocodylus in both absolute and relative terms. The stratum corneum is comparatively thin in both Rattus and Gallus, but where epidermal scales are present on the avian podotheca, such as Gallus, they are similarly covered by a thick stratum corneum, although these were not sampled in this study. In Birds, the relative thickness of the epidermal layers differs between locations, however, the epidermis is consistently thinner in Gallus than it is in Rattus and Crocodylus, a feature that has been linked to the progressive lightening of the Avian body and the evolution of flight.

In Crocodylus, the epidermis is invaginated to form the hinge area between scales. Much deeper invaginations, invading both the epidermis and dermis, are formed by hair and feather follicles in Rattus and Gallus, respectively. Underlying the epidermis is the dermis, which contains openings for the blood vessels, fat deposits, and abundant pigment cells, the latter of which are more diverse in Crocodylus and other reptiles due to their naked skin. Glands are relatively scarce and/or small in Avian and Reptilian skin, but are a salient feature of Mammalian dermis. Thick subcutaneous hypodermis dominated by fat stores and blood vessels underlies the dermis in both Gallus and Rattus, whereas it is relatively thin in Reptiles and was not sampled in the specimen of Crocodylus.

Phase-contrast optical microscopy of the Hadrosaur skin reveals an outermost (superficial) dark-coloured layer 35 75 μm in thickness, which overlies the sedimentary matrix This outer layer is composed of clearly-defined, alternating dark and lighter-coloured layers, which typically range from ~5 mm to ~15 μm in thickness. Individual layers are typically laminar or undulatory giving the entire outer layer a stratified appearance. These finer layers may deviate around sedimentary particles that are occasionally found embedded within the outer dark layer. Aside from these occasional particles, sedimentary grains are typically restricted to the sedimentary matrix underlying the dark outer layer. In places, the dark layers appear to be composed of oval substructures measuring a few micrometers in maximum dimension. The entire dark stratified layer is, in places, capped by a pale-coloured, faintly laminated region identified as barite. No other evidence of integumentary features that could be interpreted as hair follicles, feathers or glandular structures could be identified anywhere in the sample. Other epidermal/dermal features such as osteoderms and melanosomes are also absent.

Comparative histology (transmitted light optical micrographs) of the skin of Edmontosaurus cf. regalis (UALVP 53290) (A), (B) Crocodylus porosus (C), (D), Rattus rattus (E), (F) and Gallus gallus domesticus (G), (H). In UALVP 53290, the dark outer (superficial) layer corresponds to the position of the epidermis (e) in modern analogues (C)-( F). The thickness of the region identified as epidermis in UALVP 53290 varies (B); however, distinctive layering of this region (arrowheads in B) resembles the stratified appearance and general thickness of the stratum corneum in Crocodylus (D). Boxed area in (A) encompasses the enlarged area shown in (B). (I) Phase-contrast and (J) transmitted light optical micrographs of Edmontosaurus cf. regalis (UALVP 53290) skin revealing fine laminae in the outer stratified region. The outermost epidermal layer in indicated by arrowheads. Dark laminae are, in places, composed of small, lenticular or subcircular bodies (arrows in (I)). Abbreviations: b, barite layer; e, epidermis; d, dermis; ds, dark stratified region; g, sedimentary grains; h, hinge area; hs, hair shaft; hy, hypodermis; m, sedimentary matrix; p, pigment cells; s, epidermal scale; sc, stratum corneum; sg, stratum germinativum. Barbi et al. (2019).

Histological sampling of the Hadrosaur skin reveals microscopic details of the dark outer layer associated with a single epidermal scale. Specifically, this layer is distinctly stratified, composed of alternating dark and lighter-coloured layers with a total thickness of 75 μm. The topological position, overall thickness and stratified composition of the dark outer layer in UALVP 53290 is strongly reminiscent of the stratum corneum in Crocodylus ( ~145 μm thick in Crocodylus), which forms the thickest component of the epidermis in the latter. In contrast, the entire epidermis is extremely thin in both Rattus and Gallus (less than 25 μm) and the thickness of the stratum corneum is negligible compared to Crocodylus. Given the obviously scaly epidermal covering of Hadrosaurs, including UALVP 53290, it seems reasonable to infer that the dark-coloured stratified layer represents the mineralised remains of the stratum corneum. The differing thickness in what we have identified as the stratum corneum of the Hadrosaur and that of Crocodylus could be attributable to dehydration, diagenesis, taxonomic differences or any combination of these. Similar keratinous structures to those identified in UALVP 53290, together with intact remains of α - and β-keratins have been reported in non-avian Dinosaurs and contemporaneous Birds; however, these results are largely restricted to feathers and the cornified sheaths covering the unguals rather than skin.

See also...