Hyoliths are a group of extinct Palaeozoic marine animals, which possessed distinct conical calcareous shells and range in age from the early Cambrian through to the Permian. The group was one of the first Bilaterians to acquire shells and rapidly became one of the most abundant and cosmopolitan biomineralising animals in Cambrian strata. Hyoliths are subdivided into two distinct groups, Hyolithida and Orthothecida, based on a number of morphological differences. Typical Hyolithids have a four-part external skeleton, including a conical conch with a ligula, an externally fitting operculum, and a pair of curved helens that resemble oars. Orthothecids on the other hand only have two parts, a conch without a ligula and a retractable operculum. Well-preserved Hyoliths with articulated opercula are abundant in the Chengjiang Lagerstätte. Seven species of Hyoliths have been previously recorded; however, these species are difficult to define based on previous descriptions.

In a paper published in the journal Historical Biology on 20 April 2020, Fan Liu, Christian Skovsted, and Timothy Topper of the State Key Laboratory of Continental Dynamics, Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Early Life and Environments, and Department of Geology at Northwest University, and the Department of Palaeobiology at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, and Zhifei Zhang, aslo of the State Key Laboratory of Continental Dynamics, Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Early Life and Environments, and Department of Geology at Northwest University, present a redescription of the Hyolith ‘Linevitus opimus’ from the Chengjiang Lagerstätte.

After re-examination of the Hyoliths in the Chengjiang biota, Lui et al. found that specimens referred to ‘Linevitus opimus’, that are normally articulated with their cap-shaped opercula, show a high morphological similarity with members of the genus Triplicatella. Both taxa possess a nearly flat, subtriangular operculum without cardinal processes or clavicles and thus should be assigned to this genus.

The opercula and conch of Triplicatella were previously only known as components of small shelly fossil assemblages from Cambrian Series 2, Stages 3–4. Triplicatella was first reported in 1990 as a problematic, operculum-shaped fossil from the Cambrian of South Australia. Later different species of Triplicatella were subsequently discovered and described from small shelly fossil assemblages from North and North-East Greenland, western Newfoundland, Siberia and North China. Due to the lack of a co-occurring conch, Triplicatella remained a problematic fossil until 2014, when articulated conchs and opercula of Triplicatella disdoma were described in an assemblage of small shelly fossilss from South Australia, which showed that Triplicatella was closely related to Orthothecid Hyoliths.

Triplicatella opimus has a rapidly and evenly expanding conch with a subtriangular cross section. The conch of Triplicatella opimus appears strongly mineralised and all specimens show signs of brittle deformation although most specimens retain substantial topography and are partly filled with sediment. Until recently, no soft anatomy had been reported for Triplicatella opimus, but with the exquisite Konservat-preservation mode in the Chengjiang biota, specimens of Triplicatella, from fine-grained shales, are found with extraordinarily preserved soft parts, including a tentaculate feeding organ, digestive tracts and muscle scars. Soft parts are preserved as reddish-brown imprints, predominantly associated with the operculum and distributed throughout the conch. Reports of Orthothecid Hyoliths with preserved soft parts are rare and typically limited to the gut. Based on the morphological details recently reported and the new details described by Liu et al., it is clear that the material of Triplicatella from the Chengjiang biota is of significant value not only regarding the systematic affinity of Triplicatella, but also for revealing the first direct evidence of the soft anatomy of Cambrian Orthothecids.

More than 1000 Hyolith specimens have been collected from yellowish-green or greyish-green mudstone from eight localities of the Chengjiang Lagerstätte, distributed on both sides of Dianchi Lake, Kunming, eastern Yunnan, China, by the working team of the Early Life Institute of Northwest University. Most specimens of Triplicatella opimus examined here were derived from the Yu'anshan member and collected from sections at Erjie town on the west bank of Dianchi Lake, where the Hyoliths exhibit exceptional preservation of soft tissues. In Lui et al.'s material about 241 specimens from eight sections can be definitely referred to Triplicatella opimus, including some clusters with over 30 individuals. Of these, 81 specimens of Triplicatella opimus are preserved with soft tissues, 45 conchs of Triplicatella opimus have the body cavity preserved and 15 with the digestive tract preserved. In addition, 63 specimens preserve soft parts associated with the operculum and 2 specimens preserve the neck like connection between conch and operculum.

The genus Triplicatella is placed in a new family, the Triplicatellidae, along with the genera Holoplicatella and Paratriplicatella, all three genera being Orthothecid Hyoliths with oval to rectangular to subtriangular conch cross section and a planar or pyramidal operculum with dorsal and/or ventral folds but lacking cardinal processes.

The Triplicatellidae differs from other Orthothecid families by the lack of differentiated cardinal processes in the operculum. The cross section of the conch is highly variable from oval to subrectangular to subtriangular and a dorsal carina may be developed. The operculum is planar or laterally convex in a pyramidal shape and has dorsal and/or ventral folds in variable configurations that characterise individual genera and species.

Many Cambrian Orthothecids are poorly known, with descriptions often restricted to the conch, while the operculum, that seems to be much more important for classification, is frequently lacking. However, it is clear that the morphological disparity of Cambrian Hyoliths is much greater than among younger forms, which historically formed the basis of the current classification. One important feature are the clavicles, that are characteristic features of Hyolithid opercula but supposedly lacking in Orthothecids. However, many Cambrian Hyoliths seem to combine clavicle-like features with otherwise Orthothecid-like morphologies. It is possible that clavicle-like features evolved separately in different groups of Hyoliths during the early Cambrian and that such simple traits are of limited value for higher level classification. Consequently, the classification of Hyoliths is currently in a state of flux, and the relationships of Triplicatellidae to other Orthothecid families are difficult to evaluate without a major revision of the entire Order.

Members of the genus Triplicatella have a bilaterally symmetrical operculum, transversely oval to subtriangular in outline. One to four weakly to strongly developed folds on the dorsal margin, sometimes accompanied with poorly developed ventral marginal folds or invaginations. No ornamentation on operculum or sometimes with weakly defined concentric growth lines. The internal surface of the operculum is smooth without cardinal processes or clavicles, but occasionally a deep median depression exists in the sub-central part. The conch of Triplicatella is elongate, cone-shaped and gently curved, with a rounded to subtriangular cross-section matching the shape of the operculum and with occasional transverse septa.

This genus was first described in 1990 as an operculum-like fossil of uncertain affinity from South Australia. Some researchers interpreted Triplicatella as the earliest known Chiton, (Class Polyplacophora) and Simon Conway Morris suggested that it represented a Halkieriid shell. A steinkern of Triplicatella with associated conch and operculum from Australia was illustrated by Yuliya Demidenko, which indicated that Triplicatella was probably a Hyolith operculum. Unfortunately, this specimen was never described. Christian Skovsted, John Peel, and Christian Atkins also suggested Triplicatella was an operculum of a Hyolith, in accordance with the original interpretation, due to the similarity in shape and the possible muscle scars on the interior surface. This interpretation was then strengthened with the full description of Triplicatella from Australia as conchs preserved as internal moulds of a Hyolith with the operculum in place at the apertural end. The elongate cone-shaped and gently curved conch with a rounded to subtriangular cross-section, combined with the planar operculum lacking clavicles and cardinal processes, clearly indicates that Triplicatella can be placed in the Orthothecida.

The morphological features of Triplicatella, in particular the distinct series of three folds that typically occur on one side of operculum, and occasionally on both sides, clearly distinguish the genus from other taxa. The genus Sysoievia from Morocco, was proposed for Hyolith specimens that possessed an orthoconic conch with a flat, semicircular operculum ornamented by transverse growth lines. Sysoievia was considered to be similar to Triplicatella; however, Sysoievia differs from Triplicatella in having a butterfly-like pair of cardinal processes, and by lacking prominent folds on the dorsal margin of the operculum. The genus Paratriplicatella from North China possesses a slightly dorsally curved conch with a triangular cross-section, a convex triangular operculum with a fold on the dorsal side and two divergent folds on the ventral side. It was also recently considered broadly similar to Triplicatella. The most noticeable feature of Paratriplicatella, that differentiates this genus from Triplicatella, is the strongly developed ridge of tubular clavicle-like structures on the inner dorsal rim of the operculum. Holoplicatella from Spain displays a prominent notch on one side, and two widely divergent folds on the other side of the operculum. The presence of these folds does invoke a resemblance to Triplicatella, but the Spanish taxon differs in the oval shape and high degree of convexity. Holoplicatella was originally described as a potential sclerite of a larger Animal but despite the poor preservation and limited material, the general morphology of Holoplicatella suggests that this taxon represents the operculum of a Hyolith closely related to Triplicatella.

Triplicatella is known from the Lower Cambrian (Stages 3–4) of South Australia, South China, the Anabar Uplift northern Siberia, North Greenland, Northeast Greenland, western Newfoundland and North China.

Triplicatella opimus is a Orthothecid Hyolith with broad, cone-shaped conch with subtriangular cross-section; dorsum with two crests separated by deep carina tapering from apex to aperture; ventral side appears flattened and slightly convex with a curved ventral margin; apex with internal septa in larger specimens. Retractable opercula subtriangular to heart-shaped with initial shell shifted posteriorly, situated at about one-third of posterior-anterior distance, lacking both cardinal processes and clavicles; three symmetrical, posteriorly diverging (dorsal) folds; a single wide but very weak anterior (ventral) fold; two weakly expressed lateral ribs radiating from the initial shell towards anterolateral corners. External surface of conch and operculum with concentric growth lines; internal surface smooth with imprint of central muscle attachment area in operculum. Anterior unmineralised feeding organs constructed by two radial arms and an uncertain number of fine tentacles surrounding mouth; extendable pharynx connected to central muscle attachment area of operculum; posterior neck connecting operculum with conch. U-shaped, slightly undulating to folded digestive tract.

Triplicatella opimus is known only from the Yu’anshan Member (Eoredlichia Zone) of the upper part of Heilinpu (formerly Qiongzhusi) Formation, Early Cambrian, Stage 3, Yunnan Province, South China. In Liu et al.'s collection, there are 241 specimens that can be referred to Triplicatella opimus. Of these, 63 represent articulated specimens while 178 are disarticulated conchs, with some isolated opercula.

The rapidly and evenly expanding conch of Triplicatella opimus, is cone-shaped, with length ranging from 3 to 28 mm and width ranging from 2 to 14 mm. Conchs are strongly mineralised and all specimens show signs of brittle deformation. Most specimens retain substantial topography and are partly filled with sediment. The cross section of the conch was subtriangular. The dorsum bears a deep central longitudinal groove or carina, separating two rounded crests. The ventral side of the conch is flat or slightly convex. Ventral apertural margin with a rounded anterior edge, reminiscent of a ligula-like extension. Some specimens preserved in ventral view show a weakly developed marginal carina, probably due to ventral folding during compaction. Closely spaced growth lines superimposed on both ventral and dorsal sides of the conch. The apical portion of the conch often appears horseshoe-shaped after breaking along simple transverse septa sealing off the original apex.

The operculum is flat, subtriangular and cap-shaped, with width ranging from 3 to 6.6 mm and length ranging from 2.9 to 4.1 mm, matching the apertural outline of the conical conch. The apex or initial shell is indistinct, but when observable appears to be shifted posteriorly (dorsally), to a position about one-third of the entire posterior-anterior distance. There are no cardinal processes or clavicles on the internal surface. Three shorter, divergent folds are present on the posterior (dorsal) side of the operculum. The low, wide central fold is separated from the two stronger lateral folds by two deep invaginations. A single, wide and poorly expressed central fold adorns the anterior (ventral) margin. Two broad lateral ridges converge from the apex and run towards the widest lateral margin of the operculum. Ornament of fine growth lines is present on the surface along the margin of operculum.

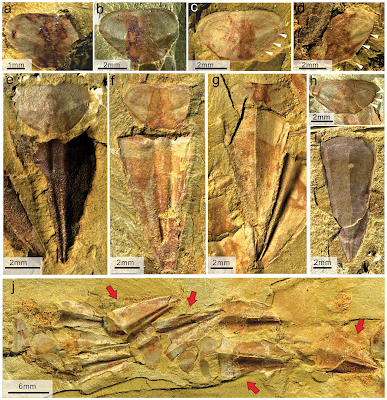

Morphology of Triplicatella opimus from the Chengjiang Biota. (a)-(d), (h) Cap-shaped opercula of Triplicatella opimus. (c)-(d), (h) Opercula preserved with the arcuate structures pointed by white arrows. (a) Specimen no. ELI H-192A. (b) Specimen no. ELI H-181B. (c) Specimen no.ELI H-191B. (d) Specimen no.ELI H-132. H, specimen no.ELI H-181B. (e) Dorsum of Triplicatella opimus associated with operculum, specimen no. ELI H-196A. (f) The imprint of the dorsum, specimen no. ELI H-115. (g) Venter overlapped the operculum ELI H-183. (i) Venter of Triplicatella opimus, specimen no. SJZ-H-1693. (j) Some individual of Triplicatella opimus preserved dorsally and ventrally in an accumulation, pointed by red arrows, specimen no. ELI H-197A. Liu et al. (2020).

Some specimens of Triplicatella opimus in the Chengjiang biota preserve exquisite imprints of soft tissue. The soft parts are preserved in the form of reddish-brown stained patches on the conch or on the internal surface of the operculum. Soft parts representing the tentaculate feeding organ were described previously and additional soft parts representing the necklike connection of the conch and operculum, the mantle cavity, muscle scars and the alimentary canal are described by Liu et al.

Triplicatella opimus, from the Chengjiang biota of South China, has been previously described as a Hyolithid, Linevitus opimus. The species has a cap-shaped operculum and a subtriangular cross section of the conch with a flattened venter, which is reminiscent of Hyolithid Hyoliths. But, it lacks both cardinal processes and clavicles in the opercula, and the arc-shaped margin of the ventral side of the conch aperture is not a ligula, but appears to match the curved ventral outline of the operculum like the prominent dorsal crests match the dorsal folds of the operculum. No remains of helens associated with Triplicatella could be observed in the exceptionally preserved biota. Abundant opercula are preserved directly associated with the conchs, and in many cases, the posterior of the operculum appears to be partially covered by the anterior margin of the conch, which indicate that the operculum could be partly withdrawn inside the conch.

Thus, there are no characteristic features of the species which suggest inclusion in the Hyolithida. Based on a comparison of the morphology of the flattened cap-shaped opercula with ventral and dorsal folds but without cardinal processes or clavicles, Liu et al. consider this taxon to be most closely comparable to the Orthothecid genus Triplicatella. Until now, five species belonging to the genus , have been described, including Triplicatella disdoma, Triplicatella sinuosa, Triplicatella peltata, Triplicatella papilo, and Triplicatella xinjia. The Chengjiang species possesses three weak dorsal folds, two low ridges towards the lateral margins of the operculum and a single, wide and quite indistinct ventral fold. However, the more weakly developed folds on the opercula when compared to other species known exclusively from acid residues may be due to the flattening of specimens during compaction, characteristic of this Konservat Lagerstätte. Regardless, the morphology of the operculum with a single ventral fold and three short dorsal folds clearly distinguish Triplicatella opimus from Triplicatella disdoma, Triplicatella sinuosa, Triplicatella papilo, and Triplicatella xinjia all of which have three ventral folds and one to four much more prominent dorsal folds. Triplicatella opimus is more similar to Triplicatella peltata from Greenland in having a distinct triangular cross section and subdued folds. However, Triplicatella peltata has a single prominent dorsal fold unlike the three dorsal folds in Triplicatella opimus where the central fold is less pronounced than the lateral folds. The conch of the Chengjiang species shows a distinct median carina forming two crests on the dorsal side, while the conch of Triplicatella disdoma from Australia is characterised by an curved and slowly expanding conch with a rounded, subtriangular cross-section, which is similar to the morphology of Triplicatella xinjia from North China. The conch is not known for any other described species of Triplicatella. Compared with Triplicatella disdoma and Triplicatella xinjia, the conch of Triplicatella opimus is more rapidly expanding with a relatively wider and shorter cone-shape, and with two crests and a deep carina on the dorsal side. The visible differences indicate that the Chengjiang species represent a separate species of Triplicatella, despite the fact that this genus is previously only known from small shelly fossil assemblages.

There is some morphological resemblance in conch morphology, particularly with the presence of two crests and a deep carina between Triplicatella opimus and ‘Hyolithes’ conularioides from Australia and Antarctica. ‘Hyolithes’ conularioides in these records were preserved as internal moulds of the conch, with a convex dorsum with a median carina separated by longitudinal crests and a flat venter. It is worth noting that the apex of ‘Hyolithes’ conularioides has been recorded with a bulbous protoconch, and Ryszard Wrona described the apex as being separated by a septum-like wall, which is reminiscent of the horseshoe-shaped apical septa in the conch of Triplicatella opimus. However, the exact relationship between Triplicatella opimus and ‘Hyolithes’ conularioides cannot be evaluated as the operculum of the latter is not known.

The operculum of Triplicatella could probably be withdrawn a short distance into the conch, because the measurement of the operculum is smaller than the apertural diameter of the conch, as is typical for Orthothecids. Although the conch shape of most specimens of Triplicatella opimus from Chengjiang is distorted by compaction, abundant specimens show partial overlapping of the posterior part of the operculum by the dorsal margin of the conch. This probably indicates that the operculum of Triplicatella opimus could be withdrawn inside the conch.

In some aspects, Triplicatella opimus is similar to Paratriplicatella shangwanensis from North China. These similarities include the convex dorsum and a flat venter with the short ligula-like extension on the venter slightly beyond the dorsal aperture and similar lateral ribs connecting the lateral margins of the opercula to the central area. However, Triplicatella opimus lacks the tubular clavicle-like structures along the arched margin on the dorsal rim on the operculum, that are characteristic of Paratriplicatella shangwanensis.

Multiple specimens of Triplicatella opimus preserve imprints of the soft anatomy as red-brownish stains. Soft parts of the operculum relating to the tentaculate feeding organ and central cylindrical mass (pharynx) have previously been described. Arcuate structures in the form of red imprints at the dorsal margin of the operculum and following the growth lines along the lateral margins of the operculum were interpreted as the margins of shell secreting epithelia. These structures are also preserved in specimens illustrated by Liu et al.

In some specimens of Triplicatella opimus, soft parts in the form of a neck-like projection are present between the operculum and conch, showing the connection of the skeletal parts of the Hyolith. The neck-like structure extends from the posterior of the operculum to the anterior of the conch and sometimes preserves obscure annulations. In one specimen, the neck-like structure is strong and thick (about 1 mm in width (approximately representing one-third of the width of the operculum) and 2.5 mm in length) with the width approximately matching the width of the central cylindrical mass of the operculum. In another specimen, the neck-like structure attached to faintly preserved soft parts without associated conch, apparently replicating the size and shape of the operculum, and an extended mass with vague spiral impressions. Liu et al. interpret these structures to represent detached soft parts of the secretory tissues of the conch margin and the visceral mass, including parts of the intestine. This specimen shows that the soft tissues of the hyolith conch were strongly connected to the operculum in the central position and could be displaced when the conch and operculum were separated. Compared with the hyolithids where the conch and operculum are connected through muscles attaching near the base of the cardinal process, the neck-like structure of Triplicatella opimus, Liu et al. suggest, functioned as an extendable attachment organ between the conch and operculum in Orthothecids like Triplicatella, which possess a flattened operculum without cardinal process.

Under a light microscope, most specimens of Triplicatella opimus from the Chengjiang biota clearly preserve a conical reddish impression inside the conch which probably represents the body cavity of the Hyolith. These red or dark stained areas in the conch centre are often located about one-third of the distance from the conch aperture, but red or yellow stained areas are also sometimes directly associated with the apertural region of the conch. These highly variable structures are not distinctive and preclude direct identification of their biological origin. Liu et al. suggest that these areas represent a partly decomposed visceral mass but without differentiated organs.

The exquisite preservation of the Chengjiang biota suggests that the digestive tract of orthothecid hyolith may be preserved as thin imprints on the internal surface of some conchs. Triplicatella opimus bears a narrow U-shaped intestine, forming spiral loops displayed on the internal surface of the ventral side and a slightly recurved to straight intestine in a dorsal position inside the conch The convoluted ventral digestive tract with a spiral loop folded into a chevron- or accordion-like structure, is preserved as a faint reddish-black tract enriched in iron. The chevron-shaped gut usually appears near the left lateral margin of the visceral cavity in the conch. On the dorsal side, the recurved straight intestine, sometimes slightly bent, appears to be aligned with the right margin of the visceral cavity.

A complete digestive system is distinctly preserved in a single specimen where the soft parts are preserved without the conch. The spiral loops are ca. 3 mm in length with a posterior width of approximately 1.5 mm, and the straight gut is about 4 mm in length. A series of at least five arcuate loops can be identified in different specimens. The recurved distal part of the intestine is present as a straight to slightly undulating and partly distended band following the longitudinal axis of the conch and appear to end in an asymmetrically placed anus.

The gently sinuous to straight part of the gut was regarded as an anal tube on the dorsal side of the conch in a series of papers. The record of both anal tube and folded gut preserved in a single specimen is rare in our material, and the structures are usually separated between part and counterpart by mud infilling. This indicates that the original location of the two parts of the guts was not in the same plane inside of the Triplicatella conch.

Additional detailed information on the digestive system was observed under Micro-CT. In some of the bestpreserved specimens of Triplicatella opimus that were infilled with sediment, fine internal structures could be resolved in the body cavity, which could not be otherwise observed on the surface of the fossil slab, highlighting the differential preservation of the soft tissues and the shell. The gut inside the conch can be clearly separated from the matrix due to the differential density, caused by the pyritisation of soft parts in the Chengjiang Biota. The internal digestive tract in the best preserved specimen is composed of a short spiral looped part with just two arcuate loops, located in the central part of the conch, and a partially preserved recurved-anal tube. Another specimen preserves a cluster of three Triplicatella opimus individuals. The three individual specimens show association of conch and operculum (two specimens preserved dorsally, one preserved ventrally with the operculum beneath the conch), and the conchs are preserved as internal moulds infilled with mud. Through Micro-CT, anatomical structures including parts of the guts and other soft tissue can be observed. One individual on the left side preserves a partial digestive tract with a spiral looped gut (about 3 arcuate loops). The other two specimens preserved obscure soft tissue, probably representing the decomposed visceral mass inside the conch.

Triplicatella has been studied for 30 years, but previous studies were limited to specimens preserved as small shelly fossils and the majority of publications focused purely on systematic descriptions because only the cap-shaped opercula were preserved. Triplicatella disdoma was not demonstrated with certainty as an Orthothecid Hyolith until 2014, through specimens discovered in South Australia preserved as internal moulds of associated conch and opercula. The discovery of Triplicatella in the Chengjiang biota extends the distribution of Triplicatella to South China, and also represents the first discovery of Triplicatella from crack-out collections in shale. The digestive system of Triplicatella consisting of a folded gut and a recurved straight intestine (anal tube) reported by Liu et al., are characteristic of Orthothecid Hyoliths and confirms the systematic position of Triplicatella among Orthothecid Hyoliths. The soft tissues exquisitely preserved in Triplicatella opimus from the Chengjiang Biota, including the tentaculate feeding organ and pharynx associated with the operculum, the necklike connection of conch and operculum as well as the folded gut provides a comprehensive understanding of the genus and adds new information on the anatomy of Orthothecida.

For Hyoliths, as a group of extinct Animals, the reconstruction of the soft parts is a necessary step towards understanding both their anatomy and evolution. However, the discovery of Hyoliths with associated soft parts is rare, with only a few published references of these recorded from the Cambrian, Ordovician and Devonian.

The specimens of Hyoliths from the Chengjiang Biota were all cracked out from fine-grained yellowish-green mudstone. However, the fossils of Triplicatella opimus documented by Liu et al. are preserved in three dimensions due to sedimentary infilling, and specimens always retain a thin coat of clay matrix inside the conchs. Many specimens preserve the operculum intimately associated with the conch, and it may be found either partly inside or just in front of the conch aperture. The opercula are often slightly displaced from the conch and in most cases appear as imprints of internal moulds. The opercula are rotated to a nearly horizontal position, invariably with the dorsal side closest to the conch, indicating that the main attachment of the operculum to the conch was along this part of the margin and this is confirmed by the position of the neck-like tissues connecting the skeletal parts. Some clusters of Triplicatella opimus show a preferential orientation probably reflecting biological concentration on the seafloor. The soft parts (consisting of the digestive tract, the body cavity, muscle scars and occasionally feeding organ) were exquisitely preserved in these specimens. These observations reasonably suggest that these animals were buried alive and in situ or experienced only gentle transportation prior to deposition.

The mechanisms and processes of taphonomy in the Chengjiang Lagerstätte are still controversial despite being widely discussed. Soft parts of Triplicatella opimus are preserved as reddish-brown-stained impressions on the sediment surface, which is a common fossilisation mode for nonmineralised organisms in the Chengjiang Lagerstätte. Analyses reveal no distinction in composition between the surface of shells and the surrounding matrix in Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-Ray Analysis mapping. However, the soft parts of Triplicatella opimus show a higher concentration of iron and phosphorous, with a slight increase in sulphur, likely indicating the presence of pyrite. The low levels of sulphur are thought to be a consequence of weathering or diagenesis. Both framboids and octahedral crystals precipitated as pyrite have been found on the remains of the soft parts in Triplicatella opimus. Framboidal microarchitecture in secondary electron Scanning Electron Microscopy images shows microcrystals (approximately 5 μm) densely arranged on the soft tissues (including feeding organ, muscle scars, body cavity, and guts) of Triplicatella opimus. Labile tissues such as these have been considered as the most reactive tissues related to microbial decay. The high concentration of iron on the surface of the fossils is most likely the result of the subsequent weathering of this pyrite.

The digestive systems of Hyoliths are different between the two orders, Orthothecida and Hyolithida. The guts of Hyolithida are generally considered to be simple, U-shaped and are mainly known from specimens preserved as compression fossils in shale from Konservat-Lagerstätten. However, the digestive system of Orthothecida has a characteristic sinuously folded gut with a straight anal tube and is often preserved in three dimensions. The three dimensionality of the Orthothecid digestive tract has been interpreted as being the result of phosphatic preservation, possibly due to partly phosphatic ingested sediments and presumably caused by microbially mediated phosphatisation. Liu et al. report that in the Chengjiang specimens the intestine of Triplicatella is preserved by means of a red mineral film containing iron-oxides, a result of weathering after diagenetic pyritisation. The reason why the guts of orthothecids from the Chengjiang Biota differ from specimens in previous reports, is probably due to different preservational modes. All material in Liu et al.'s collection comes from mudstone in the Yuanshan Member where all fossils have been subjected to high levels of compression. Lacking early cementation, substantial decay occurred prior to mineralisation, that resulted in the imprint-preservation mode for the soft parts in the Chengjiang Biota.

Although the digestive tracts of Triplicatella opimus are only partially preserved in the available specimens, the arrangement of the spiral loops is closely comparable to the spiral proximal portion of the intestine of Orthothecid Hyoliths described previously Three different configurations of the digestive tract were observed in the Orthothecid Conotheca subcurvata, from France: ‘(1) anal tube and gut parallel, straight to slightly undulating; (2) anal tube straight and loosely folded gut; and (3) anal tube straight and gut straight with local zigzag folds’. The same study measured the diameter of the conch of Conotheca subcurvata (micro-sized Hyoliths preserved the guts, with the size about 100-300 μm in diameter) to investigate whether the digestive tract changed morphology in relation to growth, concluding that the number of intestinal loops increased with the growth of the conch. Recently another study by Vivianne Berg-Madsen, Martin Valent, and Jan Ove Ebbestad documented the Orthothecid Hyolith Circotheca johnstrupi (the most complete specimen showed that the conch was about 42 mm in length and the apertural diameter was 7 mm) from the lower Cambrian of Bornholm with a highly convoluted digestive tract folded into a chevron-like structure. Considering the large diameter and remarkably uniform size of the folds, this morphology suggests an adult individual. Until now, publications regarding the digestive system of Orthothecid Hyoliths found after Cambrian Stage 3, predominantly show a sinuously looped (zigzag) intestine, coupled with a straight, tapering rectum. However, most specimens in Liu et al.'s material of Triplicatella opimus from the Chengjiang Lagerstätte, which preserve the intestine, with the operculum size ranging 5–6 mm (width) and 2.9–3.2 mm (length) and conch size ranging 9–15 mm (length) and 5–7 mm (width), show that the guts have a regular morphology consisting of a straight anal tube and a loosely folded gut. This configuration may represent an intermediate stage in the development in Orthothecid Hyoliths. The loosely folded digestive tract of Orthothecids is rarely reported, and the gut of Triplicatella opimus is broadly similar to that described from the Terrenuvian Conotheca subcurvata. Although the conch size for considering the ontology of Hyoliths cannot be excluded either due to the relatively small number of Orthothecid specimens with preserved digestive tracts. The more loosely folded gut in Triplicatella opimus from Cambrian Stage 3, compared with the more tightly folded guts of later Orthothecids, could be interpreted as evidence for support of the increased complexity of orthothecid guts.

Despite the spate of recent discoveries, the feeding strategy of the extinct Hyolitha remains controversial. Historically speaking, the most convincing arguments regarding the feeding strategy of Hyoliths have been derived from the morphology of the digestive system. The digestive tract of Hyolithids was thin, relatively long and shows a flexible U-shaped, loose configuration which is often regarded as characteristic of filter or suspension feeders that ingested soft particles. This contrasts sharply with the sediment-filled, tightly packed and convoluted guts observed in Orthothecids. A 1997 study discussed the differences in functional morphology between Hyolithids and Orthothecids based on experimental flume studies. The morphology of the Hyolithid conch together with the possession of helens appeared to strengthen the hydrodynamic stability of the individual from ambient currents. The extension of the ligula and the associated conical shape of the operculum in Hyolithids increased flow velocity, focusing the amount of suspended material, favouring Hyolithids as suspension feeders, an effect which was not observed for Orthothecid conchs with retractable opercula.

Recently, however, the documentation of the Hyolithid Haplophrentis from the Burgess Shale possessing a simple U-shaped digestive tract and an extendable gullwing-shaped, tentacle- bearing organ has added substantially to the feeding strategy debate. The presence of this tentacular feeding organ provided further evidence to support an epibenthic, suspension feeding habit for Hyolithids. The distinct morphological differences between the digestive system of Hyolithids and Orthothecids, however, cannot be ignored and most likely reflect different feeding strategies.

A straight tube in which little axial mixing occurs is probably the most common digestive tract in animals that are deposit feeders. Although a clear distinction between deposit- and suspension-feeding strategies based on digestive systems may not be feasible, deposit feeders (as sediment microbial strippers) usually increase the surface area of the gut, through, for example, extensive folding, to increase the rate of absorption. With the discoveries of the sediment-filled guts in several orthothecid taxa, evidence for the feeding strategy of the Orthothecid Hyoliths generally point towards deposit feeding.

Triplicatella was previously thought to be related to Orthothecid Hyoliths. Recently, the tentacular feeding apparatus of Triplicatella opimus from the Chengjiang Biota with a tuft-like clustered configuration of tentacles was regarded as a specialised feeding organ, used for collecting food particles directly from the sediment. The exceptionally preserved digestive system documented by Liu et al. provides new anatomical evidence to reconstruct the internal structure of Triplicatella. The gut of Triplicatella opimus forms spiral loops folded into a loose chevron-like structure with a slightly recurved to straight anal tube. A chevron-like gut is strong evidence that the organ was adapted to increase absorption of nutrients mixed with sedimentary particles. The new information on the anatomy of Triplicatella opimus unequivocally that Triplicatella opimus was an Orthothecid Hyolith and a deposit feeder. The morphology of the broad flattened ventral surface on the conch and the lack of helens suggests that Triplicatella reclined on the seafloor, probably indicating a surface microbe feeding mode of life. The accordion-shape of the gut in Triplicatella opimus, Liu et al. argue, also helps to explain the discrepant arrangement of the tentacles compared with Haplophrentis, that possessed a feeding apparatus adapted to a suspension-feeding strategy.

Based on the new information obtained recently on the morphology of Triplicatella opimus, a reconstruction of the genus, showing both the external morphology and known internal characters, is given by Liu et al. This reconstruction of Triplicatella may serve as a model for the ancestral morphology of Orthothecids and as a starting point for further research on the evolution of the typical Orthothecid body plan.

The Hyolith Triplicatella opimus is systematically revised for the first time based on exceptionally preserved specimens in mudstone from the Chengjiang Biota, South China. The material includes complete specimens of Triplicatella opimus (conch associated with operculum) and preserved soft parts and adds further evidence to support the classification of Triplicatella as an Orthothecid Hyolith. Through a series of technical methods, new internal anatomical structures in Triplicatella were revealed and provides significant new evidence concerning the general reconstruction of Hyolith anatomy, especially concerning the digestive system of Orthothecid Hyoliths. The gut of Triplicatella opimus as described by Liu et al. consists of a spiral loop folded into a chevron-like structure and a slightly recurved to straight anal tube. The gut is preserved as a reddish-brown trace enriched in iron, which conforms to the principal mode of preservation of nonmineralised tissues in the Chengjiang Lagerstätten. These observations, in combination with the previous records of characteristic Orthothecid features and a specialised feeding organ, indicate that Triplicatella opimus was a deposit feeder. The anatomical features of Triplicatella opimus from the Chengjiang biota will allow palaeontologists to achieve a complete descriptive basis for the anatomical morphology of Orthothecid Hyoliths, indicating the possibility that Triplicatella could be used as a model for the ancestral morphology of Orthothecids.

See also...

Online courses in Palaeontology.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.