The first evidence of woodworking is associated with the Early Pleistocene of Oldowan Culture of East Africa, with a number of stone tools showing wear traces and residues left when they were used to work wood. The earliest known wooden tools come from the Middle Pleistocene of Southern Africa, with waterlogged wooden items from several sites, associated with Middle Stone Age and Acheulean stone tools. One such site is at Kalambo Falls in northern Zambia, where a series of wooden artefacts were recovered in the 1950s and 1960s, from horizons which also produced Acheulean tools. These included a wood chip, and three objects with transverse notches interpreted to have been made by intentional shaping of the wood. The Amanzi Springs site in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, a stick with a possible chop mark was discovered in a waterlogged deposit which also produced Acheulean tools in the 1960s. These deposits were radiometrically dated to between 404 000 and 390 000 years before the present, from unmodified wood within the same strata. A wooden object with cut marks and fine striations from the Florisbad Spring Deposit in Free State, South Africa, was found alongside Middle Stone Age stone tools and remains of the Hominin Homo helmei; this is considered to be the oldest known clearly modified wooden object, but has not been dated beyond Middle Pleistocene.

In a paper published in the journal Nature on 20 September 2023, Larry Barham of the Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, Geoff Duller of the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University, Ian Candy of the Department of Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London, Christopher Scott, also of the Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, Caroline Cartwright of the Department of Scientific Research at the British Museum, John Peterson again of the Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, Ceren Kabukcu, again of the Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, and of the Interdisciplinary Center for Archaeology and Evolution of Human Behaviour at the University of Algarve, Melisa Chapot, also of the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University, F Melia, again of the Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, Veerle Rots of the Prehistory TraceoLab at the University of Liège, Nikki George, again of the Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, Noora Taipale, also of the Prehistory TraceoLab at the University of Liège, Peter Gethin, once again of the Department of Archaeology, Classics & Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, and Perrice Nkombwe of the Moto Moto Museum describe recently described evidence for wood being used tob build a structure in the Middle Pleistocene at Kalambo Falls.

New excavations at Kalambo Falls in 2019 recovered five modified wooden artefacts from four different areas, at different layers within the sediments, both above and below the current level of the river. A sixth wooden object showed no signs of intentional modification, but was associated with one of the modified wooden items and some Acheulian stone tools, in a layer below the current river level. One of the other modified wooden objects was also found (separately) associated with Acheulian stone tools, in a layer below the current river level. The remaining modified wooden objects were found without associated stone tools in layers above the current river level, two of them together and one on its own.

At Kalambo Falls a nine-metre-deep exposure of fluvial deposits, interpreted as having been laid down by a laterally migrating river with moderate-to-high energy flows, comprises mostly gravels and course sands, with occasional non-contiguous beds of fine sand, silt, and clay. This deposit has an elevated water table, which has preserved wooden objects and plant matter within the bottom two metres of the sequence. Wooden items are interpreted as either having been deliberately deposited by Hominins or carried to its current location by the flow of the river.

Sixteen dates were obtained from this sequence using a combination of optically stimulated luminescence dating of single quartz grains and postinfrared infrared stimulated luminescence dating of potassium-rich feldspars. These dates form a stratigraphic sequence (i.e. the older dates are below the newer dates in the succession), with one exception, and fall into three distinct age clusters. The oldest cluster, centred on 476 000 years ago (and extending approximately 23 000 years in either direction of this date) includes all of the samples from below the current river level, including two modified wooden objects, BLB3, which was found with a piece of unmodified wood and a collection of Acheulian tools, and BLB5, which was found with another group of Acheulian tools. The next cluster, centred on 390 000 years ago and extending 25 000 years on either side of that date, contained a single wooden tool, BLB2, found on its own, above the level of the current river, while the final cluster, centred on 324 000 years ago and extending 15 000 years on either side of that date, includes a pair of wooden artefacts, BLB4, found together.

It was possible to identify the wood from which the artefacts were made, but attempts at carbon dating them produced 'infinite' results, indicating they are more than about 50 000 years old. Infrared spectroscopy of these specimens showed that they had begun to mineralize, with silica beginning to replace the original wood. The tools were interpreted by comparison to later wooden tools from Holocene archaelogical sites in Zambia and the UK, as well as those made by modern Human populations.

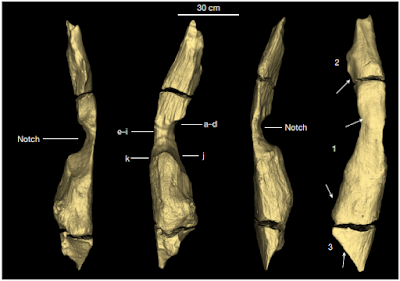

The oldest tool, object 1033 from layer BLB5, is a Large-fruited Bushwillow, Combretum zeyheri, log 141.3 cm in length and 25.6 cm in width, which was found overlying another log at an angle of 75°. Importantly, this overlying log has a notch, 13.2 cm long and 11.4 cm wide, intentionally cut into it where it rests on the underlying log, which also shows signs of modification. Bark is still present on both logs, bur is absent around the notch, emphasizing that this was intentionally cut, although this is not in doubt, due to the visible chop and scrape marks on the exposed wood within the notch.

The notch shows several areas of scrape marks, overlapping in the centre. These are 'v'-shaped in profile, up to 24 mm long and 3.2 mm wide. The end of the log is tapered, and also appears to have been modified.

The underlying log also shows signs of modification, with a series of small striations running across the grain of the wood at its mid-point, again with 'v'-shaped profiles indicative of scraping, and the end of the log which passes through the notch in the upper log showing signs of having been intentionally thinned by the scrapping of a series of notches along the grain of the wood.

Infrared spectroscopy suggests that the notch has also been modified by fire-shaping, something which was reported on another log of similar size (165 cm) previously found with Acheulian artefacts at Kalambo Falls, but not dated, which also had a wide, deep groove cut into it and tapering ends. This wood was presumed to have been part of a structure, and thought to have been modified by the actions of Early Humans. The new discovery of two logs interlocking on a similar notch, strongly supports the idea that the function was constructional in purpose, although the age of the strata from which the wood was recovered considerably pre-dates the oldest estimates for the emergence of Modern Humans.

The second collection of material below the modern river level, BLB3, comprises another collection of Acheulian tools, including flake tools, cleavers, handaxes and core axes, as well as two wooden objects, a 'v'-shaped piece of Figwwod, Ficcus sp., showing no signs of intentional modification, and a flattened branch of Sausage Tree, Kigelia africana, 36.2 cm in length and with one end carved to a point.

Barham et al. believe that this artefact has been intentionally shaped by repeated high-impact blows, in order to form a wedge. Similar wedges have been recovered from the Mesolithic Starr Car site in the UK, and are known to have been used for a variety of purposes by Aboriginal Australians, but nothing similar has ever been discovered in a Middle Pleistocene deposit.

The BLB2 horizon, dated to about 390 000 years ago produced a single wooden item, broken into two pieces which fitted together; one of these was found still embedded in the sediment, the other in the river directly below, where it had apparently fallen. The combined wooded object is about 62.4 cm in length, made of African Sausagewood, stripped of all bark and intentionally fashioned into a point, being 11.9 cm wide at the base, 6.1 cm wide in the middle, and 1.3 cm wide at the tip. The object has striations cutting across the grain of the wood in several places, these being less than 10 mm wide and convex in profile. The tip of the object is slightly rounded, which might be a sign of wear from use. or derive from its time in the river. The object is interpreted as a digging stick similar to those used historically by foragers in the Kalahari. Similar artefacts are known from the Middle Holocene of Zambia, but again the Middle Pleistocene occurrence is unprecedented.

The BLB4 horizon, dated to about 324 000 years ago, produced two wooden artefacts and no stone items. The uppermost of these is a rectangular piece of Large-fruited Bushwillow wood measuring 59.24 cm by 29.34 cm by 7.7 cm, with traces of bark and sapwood still present. This shows signs of having been flattened, but this may have been due to the weight of the sediment above it. It also has a large chop mark running across its obverse surface. Barham et al. interpret this item as a piece of tree trunk which has been intentionally cut to size, indicating a capacity to process large pieces of wood.

The second item is a Sausagewood branch, with a side branch 37.9 cm in length, tapering from a 12.3 cm wide base to a 2.1 cm wide tip. The wood has been split centrally, and has a transverse chop mark above the tip. The purpose of this artefact is unclear.

The Kalambo Falls site has yielded a number of exceptionally well-preserved, intentionally modified wooded objects, with the most recent discoveries confidently dated to the Middle Pleistocene (and previous, undated discoveries likely to be of similar vintage). This has significant implications for our understanding of the technological capabilities of earlier members of the genus Homo, which have previously only been known from stone tools. The implications are clearly that these people were capable of felling large trees, and constructing objects such as platforms, which would have required considerable skills in selecting trees, felling them, and processing the wood obtained. Since this appears to have been done with stone tools, it shows that stone- and woodworking evolved together, and helps to explain some of the larger stone tools produced as part of the Acheulean technology.

Between about 470 000 and about 274 000 years ago the Kalambo Falls site would have had an extensive forest cover and a high water table, leading to periodic flooding of the river plain. In such an environment the ability to produce raised platforms, wooden walkways, or even structures with solid foundations would have been highly advantageous.

The invention of hafted tools (tools with wooden handles) is thought to have occurred between about 500 000 and about 200 000 years ago, and would have required a good understanding of the properties of wood, and how to shape it by chopping and scraping. The interlocking logs at the lowest dated level at Kalambo Falls show a similar level of technological cognition, as well as a previously unanticipated ability to create the first built environments.

See also...