The genera Homo and Paranthropus are common in the fossil record from about 2.0 million years ago. Both are thought to have derived from an earlier Australopithecus ancestor, with the most likely ancestor for the genus Homo generally thought to be Australopithecus afarensis. However, Australopithecus afarensis is not known after 2.95 million years ago, with Hominid fossils being rare over the intervening interval, spanning the latest Pliocene and earliest Pleistocene. Examples of Paranthropus have recently been described from 2.7 million-year-old deposits in the Omo-Turkana Basin of Ethiopia and Nyayanga in Kenya, and the 2.66 million-year-old deposits at Laetoli in Tanzania, while a jawbone attributed to the genus Homo has been found at Ledi-Geraru in Ethiopia which has been dated to 2.78 million years ago, pushing the presence of both these 'Pleistocene' genera back into the latest Pliocene, while a new species of Australopithecus, Australopithecus garhi, has recently been described from 2.5 million-year-old (earliest Pleistocene) deposits in the Afar region of Ethiopia.

In a paper published in the journal Nature on 13 August 2025, a team of scientists led by Brian Villmoare of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Nevada Las Vegas describe a series of recent Hominin finds made by the Ledi-Geraru Research Project in the Afar Basin of Ethiopia.

The Ledi-Geraru sites are located at the northern end of the palaeoanthropological sites of the Afar Basin, and has produced the only known evidence of the genus Australopithecus surviving after 2.95 million years ago, as well as the earliest evidence for the appearance of the genus Homo. Paranthropus has not been found in this area, but it is unclear whether this represents a genuine absence. The two sites of Ledi-Geraru, Lee Adoyta and Asboli are to the west of the Awash River, in an area cut through by the Mille and Geraru rivers and their tributaries. The deposits here are between 2.5 and 3.0 million years old, and have been dated by Argon-Argon radioisotope stratigraphy of volcanic layers, as well as magnitostratigraphy.

Argon-Argon dating relies on determining the ratio of radioactive Argon⁴⁰ to non-radioactive Argon³⁹ within minerals from igneous or metamorphic rock (in this case volcanic ash) to determine how long ago the mineral cooled sufficiently to crystallise. The ratio of Argon⁴⁰ to Argon³⁹ is constant in the atmosphere, and this ratio will be preserved in a mineral at the time of crystallisation. No further Argon³⁹ will enter the mineral from this point, but Argon⁴⁰ is produced by the decay of radioactive Potassium⁴⁰, and increases in the mineral at a steady rate, providing a clock which can be used to date the mineral.

Magnitostratigraphy uses traces of ancient magnetic fields preserved in iron minerals in rocks to trace ancient pole reversals; the poles only have two possible orientations (north pole in the north/south pole in the south or south pole in the north/north pole in the south) and these occasionally flip, with the poles exchanging positions. Pole reversals happen more-or-less at random, with periods between reversals occurring at intervals ranching from tens of thousands to millions of years, and reflected across the globe. This creates a pattern of magnetic reversals in sedimentary rocks that can be matched in different rocks across the globe.

The first specimen described by Villmoare et al. comes from the Gurumaha Sedimentary Package, which outcrops in narrow fault-bounded exposures in the central Lee Adoyta basin and in drag-faulted blocks adjacent to basalt ridges bounding the basin to the east. This sedimentary package is cut through by the Gurumaha Tuff, which has been dated to 2.782 million years before the present. This is the unit which previously produced specimen LD 350, a 2.78 million-year-old mandible which is the oldest fossil assigned to the genus Homo.

The specimen derived from this unit, LD 302-23, is a third right lower premolar found 22 m to the southwest and 7 m bellow specimen LD 350, but still above the Gurumaha Tuff layer. This tooth measures 11.5 mm in length and 10.5 mm in width, and has a fragment of enamel missing from its lingual corner, being otherwise well-preserved. The shape of the premolar is consistent with that seen in some examples from Australopithecus afarensis, but the pattern of cusps is quite different to anything seen in any member of the genus, making it unlikely that this tooth came from an Australopithecus. It also falls within the size range of both species of Paranthropus, but is quite different in shape. Third premolars from early members of the genus Homo are quite variable, but clearly differ from both those of Australopithecus and Paranthropus. Since this tooth falls within the size and shape variation found in these early Homo specimens, Villmoare et al. assign it to the genus Homo.

The second specimen described, LD 750-115670, is an isolated lower fourth premolar, found at the base of an 8 m exposure of fossiliferous mudstones and sandstones at site LD 750. This site is located stratigraphically between the 2.63 million-year-old Lee Adoyta Tuffs and the 2.59 million-year-old Giddi Sands Tuff.

The tooth crown is unworn, with all cusps preserved, although the root is broken off, giving a maximum root height of about 2 mm. The lack of wear may imply that the tooth was unerupted at the time of death. The tooth is 12.4 mm long and 11.4 mm wide, placing it at the upper end of the size range for Australopithecus afarensis or Australopithecus africanus, and too large for Australopithecus anamensis. No lower jaw or teeth are known for Australopithecus garhi, but the specimen is within a plausible size range for the species. It also falls within the size range of both Paranthropus species, but again is quite different in shape. It does resemble several fourth premolars attributed to early Homo, though Villmoare et al. note that these attributions are provisional, and that it is difficult to distinguish between early Homo and Australopithecus fourth premolars. Since this tooth lacks any distinctively Homo features, Villmoare et al. provisionally assign it to aff. Australopithecus sp..

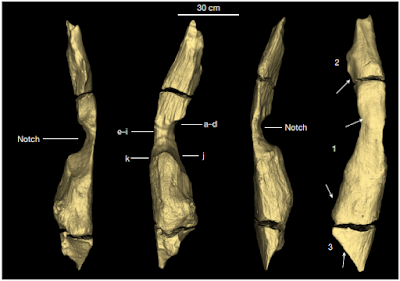

A set of five associated lower molars were discovered at a site identified as LD 760, a flat sandy area approximately below the 2.63 million-year-old Lee Adoyta Tuffs. These are worn, with dentine exposed on their outer cusps, and wide for their lengths, giving them a squarish profile. Notably, the third molar is larger than the second molar, and the second molar is larger than the first, the first and second molars a relatively square, and the first and second molars lack a seventh cusp, all traits compatible with Australopithecus afarensis, but not early Homo. However, these teeth also differ from those of Australopithecus afarensis in several ways; they do not taper towards the rear, and lack a distinctive bilobate buccal contour.

LD 760 molars compared to Australopithecus afarensis. Left molars from Ledi-Geraru specimen LD 760 (left) and Hadar specimen A.L. 400-1 (right). Measurements in mm of the LD 760 molars (length × width): LM1: 13.3 × 13.4, LM2: 14.5 × 14.6, LM3: 14.0 (estimated) × 15.7, RM1: 13.2 × 13.1, RM2: 14.8 × 15.2. Specimens are oriented with their buccal surfaces to the left and mesial surfaces up. Villmoare et al. (2025).

LD 760 molars compared to Australopithecus afarensis. Left molars from Ledi-Geraru specimen LD 760 (left) and Hadar specimen A.L. 400-1 (right). Measurements in mm of the LD 760 molars (length × width): LM1: 13.3 × 13.4, LM2: 14.5 × 14.6, LM3: 14.0 (estimated) × 15.7, RM1: 13.2 × 13.1, RM2: 14.8 × 15.2. Specimens are oriented with their buccal surfaces to the left and mesial surfaces up. Villmoare et al. (2025).A partial upper molar was also recovered from this locality. This preserves the lingual grove of the tooth, which appears to be quite distinct. In the upper molars of Australopithecus garhi this groove is indistinct. Furthermore, the upper molars of Australopithecus garhi has a greatly reduced hypercone cusp, which leads the protocone cusp to take on a triangular shape. The hypercone is absent in the LD 760 specimen, but the protocone is present, and shows no sign of modification due to a reduced hypercone. However, the sample size for Australopithecus gahri is small, so this cannot be ruled out as a natural variation within the species.

Also found at the LD760 site were a right maxillary (upper) canine, a complete left maxillary lateral incisor and a left fragmentary maxillary central incisor. Thecanine (LD 760-115979) is well preserved, lacking only the tip of the root. This has mesial and distal interproximal contact facets (wear marks caused by contact between teeth), with the interproximal contact facet having a matching distal interproximal contact facet on the second incisor. This means that the second incisor and canine were in contact, something typical of the the genus Homo, and unlike the situation in many Australopithecus specimens (including the Australopithecus gahri maxilla BOU-VP-12/130) where these two teeth are separated by a diastema (this trait is variable in Australopithecus afarensis, which may-or-may not have a diastema, so this could conceivably also be the case in Australopithecus gahri). The canine is also notably large, towards the upper end of the size range seen in Australopithecus (and much larger than anything seen in Paranthropus).

The canine of Australopithecus gahri has a unique structure, with a shallow distal basin reminiscent of a talon which is contiguous with a wide wear furrow which runs along the entire post-canine dental row, something not seen in any other Hominin, and absent in the LD 760 canine. Morphologically, this tooth resembles those of Australopithecus afarensis, however, it has different wear patterns. In Australopithecus afarensis wear is mostly seen on the distal crest, whereas in the the LD 760 canine it is predominantly on the apex, suggesting a difference in diet and/or lifestyle.

The LD 760 individual clearly does not belong to Paranthropus, and is not morphologically consistent with any described species of Australopithecus. However, since it resembles Australopithecus afarensis more closely than anything else, Vallmoare et al. refer it to Australopithecus sp. indet.

The final specimens discussed come from the Giddi Sands unit in the Asboli region. These were found immediately below the 2.593 million-year-old Giddi Sands Tuff, and comprise a partial upper left first molar, and two fragments of an upper left second molar, which can be assembled to form a whole crown. They show little wear, and are close in shape to those of Australopithecus afarensis, although they lack the pronounced lingual occlusocervical sloping and general 'puffy' appearance of the molars of that species. They closely resemble the molars of early Homo specimens such as the 2.3 million-year-old specimen from the Busidima Formation at Hadar, or the 2.5-2.4 million-year-old specimen from Mille-Logya. It is quite different in form from the molars of Australopithecus gahri, and is small compared to the molars of either Australopithecus gahri or Paranthropus.

Vallmoare et al. believe that although the Ledi-Geraru material is very limited, it provides clear evidence that both Australopithecus and Homo were present during the 3.0-2.5 million years ago interval, suggesting that multiple non-robust Hominin lineages were present in East Africa before 2.5 million years ago.

The molar fragments from Asboli sufficiently resemble the Homo specimens from Hadar and Mille-Logya that Vallmoare et al. are confident that they represent the same species. However, they predate the older of these specimens (Mille-Logya) by at least 150 000 years. This adds to the evidence for an early appearance of Homo as Ledi-Geraru previously established by the LD 350-1 mandible, as does the LD 302-23 premolar which Vallmoare et al. describe from the Gurumaha sedimentary package.

The LD 750 and LD 760 material both come from the Lee Adoyta sedimentary package, although they are separated by 24 m of strata and the 2.63 million-year-old Lee Adoyta Tuffs. Nevertheless, both appear to represent a single species of Australopithecus (an assumption based in part upon the unlikelyhood of two similar species of Austrlopithecus coexisting in the same area).

Vallmoare et al. consider four potential explanations for this material. Firstly, they might represent a late surviving population of Australopithecus afarensis (approximately 350 000 younger than the current youngest member of the species, from the Kada Hadar 2 Submember at Hadar). Secondly, they may represent an unknown species of Australopithecus ancestral to Paranthropus; the presence of Homo in this region implies that the Homo and Paranthropus lineages had diversified by this time, but Paranthropus itself appears to be absent. However, the oldest currently accepted member of the genus coming from about 2.7 million years ago from Nyayanga in Kenya and 2.66 million years ago from the Upper Ndolanya Beds at Laetoli in Tanzania, which makes this scenario less likely. Thirdly, they may represent earlier examples of Australopithecus gahri, which have not yet developed the distinctive features of the 2.5 million-year-old specimen BOU-VP-12/130, although the lack of similarities makes this unlikely. Finally, these specimens represent a new, as yet undescribed, species of Australopithecus.

Villmoare et al. conclude that were at least three species of Hominins present in the Afar Region between 3.0 and 2.5 million years ago, Australopithecus gahri, an unknown species of Homo, and an unknown species of Australopithecus. At the same time, Australopithecus africanus was still present in South Africa, and Paranthropus had already appeared in Kenya, Tanzania, and southern Ethiopia. The Ledi-Geraru environment was drier and more open than was typical for Australopithecus, very much the sort of environment associated with appearance and proliferation of the genus Homo, suggesting that, at least locally, Australopithecus may have been able to adjust to these more open environments, at least for a while.

See also...

.png)

%20(1)%20(1).png)