Southern and South Central Africa are home to numerous rich copper deposits, including the sediment-hosted

deposits in the Central African Copperbelt, which runs along the border between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia, the similar deposits of the Magondi Belt of northern Zimbabwe, the early Precambrian metavolcanic 'greenstone belts' of southern Zimbabwe, eastern Botswana and

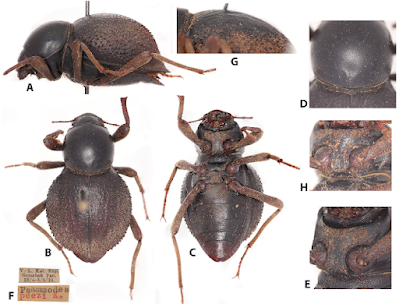

northeastern South Africa, the Limpopo Mobile Belt (mostly gneisses) parallel to the border

between Zimbabwe and South Africa, and the Phalaborwa Igneous Complex (a carbonatite) in

northeastern South Africa. All of these deposits were well known to local populations, and extensively worked for their ores, long before the arrival of Europeans in the area. These pre-colonial mines were the subject of a number of studies between 1920 and 1975, but subsequently have been largely overlooked, and many are now in danger of being lost due to large scale modern mining in the same areas.

The earliest known evidence of copper mining in the region is at Kansanshi in northwestern Zambia, which dates from the fourth century AD, about the same time as the first Iron Age farmers arrived in the region, and the ore appears to have been extracted using iron tools. Ore appears to have been processed at Kansanshi, and transported overland to Kipushi on the Kafue River for smelting; a distance of over 100 km. A variety of smelting techniques have been recorded from ancient sites in the Copperbelt, including tapping the metal directly into molds, allowing it to gather in the bottom of furnaces, and collecting it from prills (globules) trapped within the slag of melted ore. It was then typically worked with iron tools, including hammers and wire-drawing plates. The most common usage of copper in Southern Africa appears to have been to make jewelry, but stores of copper ingots have been found in a variety of locations, and it has been suggested that these may have been used as currency. These copper ingots have been the subject of a number of studies, which have focused on their age, distribution (there are several different forms, found in different areas), and possible uses, although the precise origin of the different forms of ingot have yet to be determined.

In a paper published in the journal PLoS One on 22 March 2023, Jay Stephens of the School of Anthropology at the University of Arizona, and the ArchaeometryLaboratory at the University of Missouri, David Killick, also of the School of Anthropology at the University of Arizona, and Shadreck Chirikure of the School of Archaeology at the University of Oxford, and the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cape Town, present the results of a study of a selection of Southern African copper ingots, using isotopic and trace element data to try to connect them to specific mining areas.

Locations of prehistorically exploited mines in southern Africa. Stephanie Martin and Jay Stephens in Stephens et al. (2023).

The exact age of the ores of the Copperbelt is uncertain. The copper is thought to have accumulated in a sedimentary basin between the Zimbabwean and Congo cratons (proto-continents), which came together to form part of the super continent of Gondwana between 650 and 500 million years ago. As this basin closed, the sediments were compressed and folded, before undergoing a series of faulting events, forming the Damaran-Lufilian Arc, which runs along

the coast from western South Africa, through Namibia, and up into Zambia and the southern Democratic Republic of Congo. The formation of the copper minerals may have happened during, or prior to, the Lufilian (or Pan-African) Orogeny, though they were certainly remobilised and redistributed during this orogeny. The ore bodies appear to have received two influxes of uranium, one about 650 million years ago, and one about 530 million years ago, This has resulted in the presence of the isotopes lead²⁰⁶ and lead²⁰⁷, the decay products of uranium²³⁸ and uranium²³⁵, within the Copperbelt ore bodies.

The Kipushi Mine lies within the Copperbelt, but access deposits geologically distinct from other Copperbelt ore bodies, being younger, at about 450 million years old, higher within the stratigraphic column, and geochemically distinct. Kipushi is the largest of three zinc-lead-copper deposits within the Copperbelt area, with the others being Kabwe, also in Zambia, and Tsumeb, in Namibia. The isotopic signal of these deposits is quite different from that of the other Copperbelt ores, lacking in the radiogenic lead component. It is also possible to distinguish Kipushi ores from Kabwe and Tsumeb ores chemically, with the Kipushi ores highly enriched in copper, zinc, arsenic, silver, antimony, and lead, both within the sulphide ores themselves, and within the supergene zone (area at the top of or above the ore that becomes enriched in metal elements as water peculates through the ore body, dissolving metal ions then redepositing them), which is typically of a malachite colour and enriched in copper arsenate, carbonate, oxide, phosphate, sulfate, vanadate, and chloride minerals.

The Magondi Belt originally formed as a back-arc basin between 2.2 and 2.0 billion years ago, and was deformed and metamorphosed by the Magondi Orogeny between 2.0 and 1.9 billion years ago. These deposits were further deformed and re-deposited during the Pan-African Orogeny, about 550 million years ago. The ores of the Magondi Belt contain radiogenic lead isotopes, with a lead²⁰⁷/lead²⁰⁴ to lead²⁰⁶/lead²⁰⁴ ratio distinct from that of the Copperbelt.

Within the Magondi Belt, ores are generally stratiform, concentrated within the Deweras and Lomagundi group rocks on the eastern margin of the belt. Most of these deposits host only copper, or copper and silver with smaller amounts of gold, lead, platinum, and uranium, although the Copper

Queen and Copper King deposits on the western margin of the belt contain zinc-lead-copper-iron-silver ores.

Copper ingots from Southern Africa have been known since the 1960s, when the first such ingots were discovered in a burial at Sanga in the Upemba Depression of the southern Democratic Republic of Congo, and at Ingombe Ilede in the Zambezi Valley in Zambia. The oldest known ingots are of a type known as 'Ia'. These are small, rectangular ingots, dating from the 5th to 7th centuries AD, known from sites in the Copperbelt and at

Kumadzulo. Two 'fishtail' ingots from Kamusongolwa Kopje, in Northwestern Province, Zambia, and Luano Main Site, in Central Province, also Zambia, dated to between the 9th and 12th centuries AD, are also considered to belong to the 'Ia' type.

A second type of ingot, named HIH, appears at sites dating from the ninth century onwards, and is considered to be linked to a significant increase in the production and use of copper. These ingots tend to be 7-20 cm in length, and are 'H' shaped, with two short arms at each end of a longer central bar. These ingots are known from 9th to 14th century sites from the Upemba Depression in the Southern Democratic Republic of Congo to Great Zimbabwe, with a number of molds being known as well as the ingots themselves. HIH ingots appear to have been mainly trade items until the 13th century, but in the 14th century they became prestige goods in their own right, and are often found within Kambabian-period burials. All the known HIH ingots from Great Zimbabwe date from the 14th century.

In the 14th century two, apparently separate, spheres of ingot circulation developed. In the western Copperbelt and Upemba Depression, small HX and HH type croisette (cross-shaped) ingots, between 0.5 and 7 cm across, are found, with molds for these ingots found across this range. At the same time, in the eastern Copperbelt, at Ingombe

Ilede in the Zambezi Valley, in northern Zimbabwe, and in the

Dedza area of Malawi, much larger HXR type ingots appear. These are X-shaped, with a flange around their outer edge, 20-30 cm in length and weigh 3.0-5.5 kg. Molds for these ingots are only known from the eastern Copperbelt, although this includes Kipushi.

'Ia' (rectangular and fishtail) and croisette ingot typology. Stephens et al. (2023).

These HXR ingots have been a subject of considerable archaeological interest, being known from the Ingombe Ilede burial site (eight ingots), eight from a hoard in the Dedza area of Malawi, and two from the Chedzurgwe site in Zimbabwe, and thirty other sites within northern Zimbabwe having produced a further sixty examples, often accompanied by pottery of a similar style to that of Ingombe Ilede. Oral histories from the area record that copper crosses were obtained by trade from a people called the Va-Mbara from the Urungwe area, who were renowned for their metal-working skills, and the sixteenth century Portuguese explorer Antonio Fernandes recording that such metal crosses were produced by a people called the Mobara from the land of Ambar, which maybe a reference to the same group.

Highlighted archaeological sites, geological districts, and geological mines. Stephens et al. (2023).

The copper crosses mentioned by Fernandes and the HXR ingots have been thought to be the same thing for some time, potentially suggesting that Fernandes' records might provide an insight into the origin of these ingots. Fernandes himself believed that the ingots originated from close to the 'Copper rivers of Manyconguo'. which may be a reference to the Niari Basin ore deposits, which lie near the mouth of the Congo

River, and which were exploited by the Kongo Kingdom at this time. This is about 2100 km from the area where these ingots are found today, making it highly unlikely that Fernandes was correct on this issue, but several researchers have suggested that this might indicate that the ingots originate from the Copperbelt, which is in the same direction as Niari Basin, albeit considerably closer.

Few of these large ingots have been directly dated, although, based upon their archaeological context, it is assumed that they were manufactured between the 14th and 18th centuries. The majority HXR ingots have been found at sites which have also produced Ingombe Ilede style ceramics, although examples are also known from Musengezi and Mutapa culture sites. As with earlier ingots, these items seem to have been used both for trade and as prestige items, something recorded by the Portuguese and which matches with the contexts in which they were discovered.

At some time in the 18th century, production of these HXR ingots ceased, with their replacement by X-shaped un-flanged handa ingots, and I-shaped Ib and Ic ingots, which could weigh up to 30 kg. These were frequently recorded by European visitors to what are now Malawi, Zambia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, although they have never been recorded from the Zimbabwean Plateau.

Additionally, copper ingots of the lerale (rod-shaped) and musuku (cuboid) types were produced in South Africa, while nail head ingots, and more informal bun and bar ingots were produced in both South Africa and Zimbabwe, during the 12th to 20th centuries, although these are outside the scope of Stephens et al.'s current study.

Copper ore invariably contains a small amount of lead, with an isotopic composition dependent on the age, type, and other geological characteristics of the rock. This lead is incorporated into the smelted copper with its isotopic signature unaltered, something which has previously been used to trace the origin of copper artifacts from archaeological sites in Europe and the Mediterranean region since the 1980s. More recently, the technique has been applied to copper, bronze, and tin archaeological material from Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa with some effect.

Stephens used an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry system at the University of Arizona to analyze 34 copper samples taken from ingots, 33 of which came from the collections of the Museum of Human Sciences in Harare, Zimbabwe and the Livingstone Museum in Livingstone, Zambia, for their lead isotope composition, and proportions of chromium, iron, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, arsenic selenium, molybdenum, silver, cadmium, tin, antimony, and lead.

The type Ia rectangular and fishtail ingots produced similar lead isotope ranges, all of which were consistent with an origin somewhere within the Copperbelt, as well as a radio-isotope age of 589 ± 15.4 million years, also consistent with an origin within the Copperbelt. It was not possible to assign any of the ingots to a specific mine within this region.

The HIH and HXR croisette ingots from Ingombe Ilede and northern Zimbabwe can be split into two groups, both of which contain both types of ingot. The first group, comprising eight HIH ingots and four HXR ingots, match the type Ia ingots in their lead isotope ratios, and a radio-isotope age of 627.25 ± 3.57 million years; again consistent with a Copperbelt origin, but not sufficient to pin that origin down to a specific mine.

The second group, comprising three HIH and 13

HXR ingots, as well as three large HH ingots from the Upemba Depression in the Democratic Republic of Congo, have isotopic signatures consistent with having originated from the Kipushi Mine deposit within the Copperbelt.

Another HXR ingot, recovered from the Kent Estate in Zimbabwe, has a quite different lead isotope ratio. This appears to match with ores from the Magondi Belt, although Stephens et al. are unable to confirm this with any confidence as relatively few ore samples from Magondi have been analysed.

Chemically, the Ia type bar and fishtail ingots are remarkably pure, containing less than 5 μg per gram of chromium, selenium, molybdenum, silver, cadmium, tin, antimony, and lead, and less than 50 μg per gram of nickel, zinc, and arsenic. The levels of cobalt and iron are slightly higher (if quite variable), with 5-204 μg per gram of cobalt and 27-71 μg per gram of iron. This high level of purity, and pattern of elements has previously been observed in copper artifacts from the Democratic Republic of Congo and Botswana. Once again, this elemental composition is consistent with the metal having originated within the Copperbelt, but is not sufficient to pin it down to a specific mine, with about 150 known mines potentially capable of having made these ingots.

The HIH and HXR croisette ingots were split into two groups on the basis of their isotopic composition, and their chemical content was found to match this. The first group, comprising eight HIH ingots and four HXR ingots, which were had similar isotope ratios to the type Ia ingots, also had similar chemical compositions, with chromium, zinc, selenium, molybdenum, cadmium, tin, antimony, and lead all under 5 μg per gram, silver under 20 μg per gram, nickel concentrations of 5-42 μg per gram, iron concentrations under 50 μg per gram, and cobalt values of 2-144 μg per gram. This is again sufficient to suggest that these ingots originated from the Copperbelt, but not where, although the variation in nickel, cobalt, and silver seen across these and the type Ia ingots suggests that more than one mine was involved in production.

The second group, comprising three HIH and 13 HXR ingots, have much higher levels of zinc, at 13–146 μg per gram, with a mean of 61 μg per gram, arsenic, at 240–2515 μg per gram, with a mean of 869 μg per gram, silver, at 88–1966 μg per gram, with a mean of 1254 μg per gram, antimony, at 2-111 μg per gram, with a mean of 29 μg per gram, and lead, at 14-1465 μg per gram, with a mean of 378 μg per gram. Concentrations of cobalt, nickel, selenium, molybdenum, cadmium, and tin mostly remain below 5 μg per gram. The lead isotope ratio of these ingots matches the ore from the Kipushi Mine. Three large HH ingots which were analysed in an earlier study led by Frederik Rademakers were found to have similar chemical compositions and lead isotope ratios to this group. The enrichment in chalcophile elements (zinc, arsenic, silver, antimony, and lead) may have happened within the malachite ore, where ions of all of these elements could substitute for copper, or come from the supergene deposits (deposits which lie above the ore body) which are a similar colour to the malachite ore, and could be introduced accidentally.

A single HXR ingot from Kent estates in Zimbabwe does not fit into either of these groups. This ingot has chromium, cobalt, zinc, arsenic, molybdenum, cadmium, tin, and antimony, levels below 10 μg per gram, lead and nickel below 30 μg per gram, an iron level of 490 μg per gram, selenium at 145 μg per gram, and silver at 1572 μg per gram. This enrichment in selenium and silver, while most other elements are depleted, is typical of ores from the Deweras Group of the Magondi Belt, such as those accessed by modern mines at Mhangura (formerly Mangula) and Norah. These ores also contain uranium, which could account for the high proportion of radiogenic lead in this ingot.

Stephens et al.'s study suggests that croisette ingots were manufactures in at least three separate locations: the Central African Copperbelt, the Kipushi deposit, and the Magondi Belt. All the ingots appear to be made from ore from a single source, without any evidence of ingots being made from mixed ores or recycled copper from multiple sources, something which has also been observed in previous studies.

Inferred provenance conclusion for the rectangular, fishtail, and croisette ingot in the study. Provenance results indicate that

objects travelled significant distances to reach certain destinations and that interactions between the Copperbelt and areas further south can be traced

back to the 6th-7th century. Stephens et al. (2023).

Sixteen of the ingots have elemental and isotopic signatures which match the ores of the Central African Copperbelt, something which has previously been observed in copper objects from the Upemba Depression in the southern Democratic Republic of Congo and the Tsodilo Hills in northwest Botswana. These ingots are depleted in chalcophile elements and enriched in siderophile elements such as cobalt and nickel, as are the ores of the Copperbelt, although neither the elemental nor isotopic composition of the ingots allows any more precise diagnosis.

Molds for rectangular or fishtail ingots have never been found within the Copperbelt, but numerous croisette ingot molds have been found, along with considerable evidence for precolonial mining. More than 100 precolonial mines had been recorded in the Copperbelt by 1906, the majority in an arc from Kolwezi to Kipushi in the Katangan Copperbelt of the Democratic Republic of Congo, but with examples in the Kafue Hook and Domes Region of the Zambian Copperbelt.

The ingots which Stephens et al. attribute to this source include e all three recorded rectangular and fishtail ingots

from Zambia, dated to before the 12th century, an HIH ingot from the Harare tradition site

of Graniteside, an HXR ingot from burial 8 at Ingombe Ilede, dated to the 15th-17th century, and , 10 HIH

and HXR ingots from farms and towns in northern Zimbabwe. These ingots appear to have frequently been carried long distances from their point of origin; about 600 km to the 6th-7th settlement at Kumadzulo near Victoria Falls in southern Zambia, and as far south as Harare in Zimbabwe. This distribution also demonstrates that cultures such as Ingombe Ilede in southern Zambia, Harare in Zimbabwe and

Musengezi in northern Zambia were in contact with one another and part of a common trade network.

Another 16 ingots could be linked directly to the Kipushi deposit on the southern border of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The isotope signature of these ingots form a particularly tight cluster even within the range observed at Kipushi, which Stephens et al. assume relates to the oxidized surface deposits, which are known to have been accessed by a precolonial mine. A fragment of casting spill from a furnace by the Kafue River in Zambia close to Kipushi, and a chunk of malachite ore found nearby, also match this signature. These ingots are also enriched in chalcophile elements, but depleted in siderophile elements, something observed at Kipushi in both the malachite ores, and the overlying carbonate deposits. This has also been seen in three HH ingots previously analysed, and presumed to have come from the same source.

There is a great deal of archaeological evidence for precolonial mining at Kipushi, albeit all on the Zambian side of the border. This includes at least 57 discrete smelting sites with slag heaps, two large habitation sites, one campsite, and 71 individual croisette molds (for both HIH and HXR ingots). This activity appears to have been going on since at least the ninth century, with a significant expansion in the fourteenth, which coincides with the first appearance of HIH ingots in cemeteries of the Upemba

Depression and in the archaeological record of Zimbabwe.

The ingots considered to have come from Kipushi include undated HIH ingots from northern

Zimbabwe, two HXR ingots from Ingombe Ilede (one from burial

2 and one from burial 8), dated to the 15th-17th centuries, two HXR ingots from Chedzurgwe in Zimbabwe dated to the 16th century, and nine HXR ingots discovered at undated surface sites in northern Zimbabwe. These ingots would have been transported 500 km to Ingombe Ilede and up to 780 km for finds

near Harare, Zimbabwe.

Stephens et al. also note that there appears to have been a distinct shift in where the HXR ingots were being made, with 15 of 18 HXR ingots analysed coming from Kipushi, and HXR mold fragments associated with the increase in activity at that location, suggesting that Kipushi became the major producer of these ingots at this time, although quite who was responsible for this activity is unclear.

A single ingot, from Kent Estates in Zimbabwe, had an isotopic signature consistent with an origin in the Magondi Belt. There is considerable evidence for precolonial mining within this area, in the areas where the modern Alaska, Angwa, Mhangura, Norah, and Silverside mines are sited, although this has not been studied much by archaeologists. A mold for an HXR ingot was found at the Golden Mile Mine, which is about 20 km away from the Mhangura Mine in Zimbabwe. This appears to have been copied from the form being used in the Copperbelt, but to have been used to make ingots from local copper.

Ninety four HIH and HXR copper ingots have been recovered from archaeological sites in the Zambezi Valley and across the

Zambezi Plateau. It was originally assumed that these were made locally, using copper obtained from the copper deposits of the

Magondi Belt of Northern Zimbabwe. However, the subsequent discovery of molds for these types of ingots at Kipushi and other sites within the Copperbelt of northern Zambia and the southern Democratic Republic of Congo presented an alternative source, with the ingots potentially being transported to southern Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Stephens et al. analysed 29 of these 94 ingots geochemically, and conclude from this that 28 of them originated within the Copperbelt, and 16 at Kipushi. This suggests that a trade network carrying copper ingots (and presumably other goods) from the southwest of Zambia was in place by the sixth or seventh century, and that this had reached as far as Botswana by the eighth century. By the fourteenth century copper from the Copperbelt was reaching east to the

middle Zambezi Valley, and the Urungwe District of northwest Zimbabwe, where pottery in the style of Ingombe Ilede in the middle Zambezi Valley has also been found. HIH and HXR ingots have not been reported from Botswana, but copper goods with similar chemical signals to the Copperbelt ingots has been found there. In addition, some HXR ingots do appear to have been manufactured in Zimbabwe.

See also...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Twitter.

%20(1)%20(1).png)

%20(1).png)