Sharks appear in the fossil record between 450 and 420 million years ago (all possible specimens older than 420 million years old are fragmentary and disputed), and have been important marine (and in the Carboniferous and Permian, freshwater) predators ever since. They form an important part of the marine fossil record in many areas, and are occasionally used for stratigraphy (dating rocks), though often they are usually only represented by their teeth, which are mineralized and grown and shed throughout their lives, rather than their skeletons, which are comprised entirely of cartilage, and consequently have poor preservational potential.

In a paper published in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica on 12 January 2012, Charles Underwood of the Department of Earth and Planetary Science at Birkbeck College and Jan Schlogl of the Department of Geology and Paleontology at Comenius University describe a collection of deepwater Shark's teeth from the Cerová−Lieskové locality in the Malé Karpaty Mountains in Slovakia. This is a claypit noted for a broad range of vertebrate and invertebrate fossils from the Early Miocene of the Central Paratethys Sea. These fossils are thought to be important, as while Shark teeth are well represented in the fossil record, deepwater Sharks are relatively poorly known.

Ten incomplete specimens are referred to the genus Galeus (Sawtooth Catsharks), though not assigned to any species. These are small specimens, the largest being about 0.7 mm. The genus Galeus first appears in the fossil record in the Early Miocene of France, and is widespread in the Atlantic and Pacific today.

Teeth assigned to the genus Galeus from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. (A) Anterolateral tooth in labial (A₁) and lingual (A₂) views. (B) Anterolateral tooth in labial view. (C) Posterior tooth in labial view. (D) Anterior tooth in labial view. (E) Anterolateral tooth in labial view. (F) Anterolateral tooth in labial view. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

A single, 2.2 mm, broken tooth is assigned to the genus Squatina (Angel Sharks). Modern Angel Sharks are found globally in tropical and temperate seas; most species are restricted to shallow waters, though one species, the Sand Devil (Squatina dumeril) is known to migrate seasonally into deep water. Angle Sharks are flattened Sharks resembling Skates and Rays (to which they are not closely related) and living on the sea bottom. Angel Sharks are considered to belong to a separate order (Squaliformes) which first appears in the fossil record in the Late Jurassic, with members of the modern genus (Squatina) known from the Middle Cretaceous.

Partial tooth assigned to the genus Squatina from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

Three oral and one incomplete rostral teeth (rostral teeth are projections on the side of the snout of a Sawshark or Sawfish) are referred to the genus Pristiophorus (Five-gilled Sawsharks), and assigned to a new species, Pristiophorus striatus. Sawsharks resemble Sawfish (which are also Sharks), but are found in deepwater, while the Sawfish are shallow-water dwellers. The two groups are not closely related, Sawfish being related to Skates and Rays (Batoidea). The oldest Sawsharks appear in the Lart Cretaceous of the Lebanon, about 85 million years ago, modern Sawsharks are found in the Indian and Pacific Oceans as well as the Caribbean, though their fossil record suggests they were more widely distributed for much of the Tertiary.

Teeth assigned to the species Pristiophorus striatus from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. (H) Lateral tooth in labial (H₁), occlusal (H₂), and basal (H₃) views. (I) Partial rostral tooth in lateral view. (J) Anterior tooth in labial (J₁), occlusal (J₂), and basal (J₃) views. (K) Lateral tooth in labial (K₁) and basal (K₂) views. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

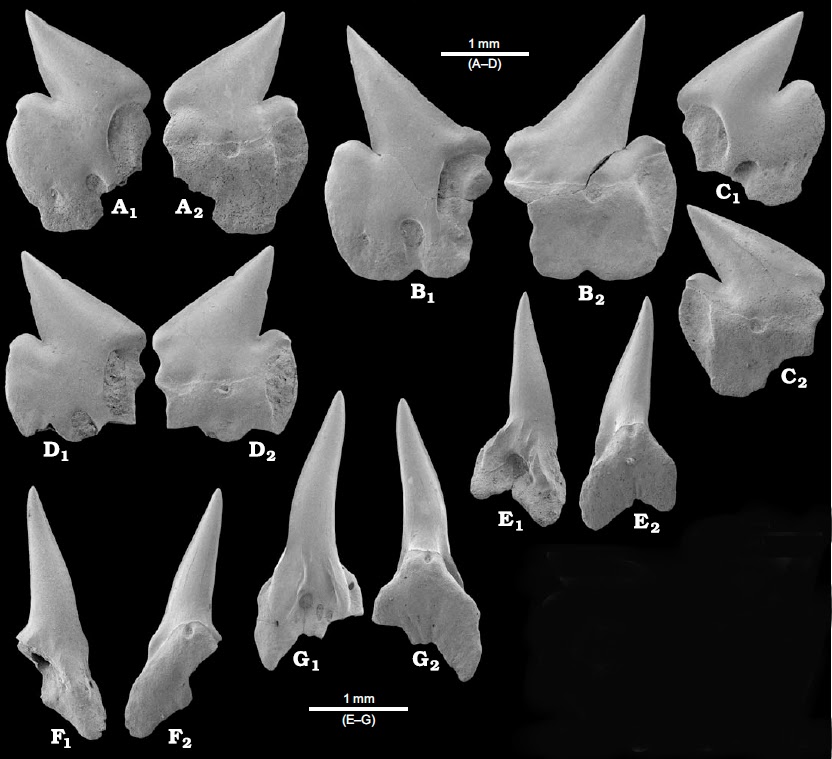

A large number (236) of teeth are assigned to the genus Squaliolus (Pygmy Sharks or Deep-sea Dogfish), and tentatively to the species Squaliolus schaubi, a species previously described from the Miocene of France. Modern Pygmy Sharks are small deepwater species with specialized organs that house bioluminescent bacteria. They are a form of Kitefin Shark (Dalatiidae), a group that first appear in the fossil record in the Early Cretaceous of Germany.

Teeth tentatively assigned to the species Squaliolus schaubi from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. (A) Lower tooth in labial (A₁) and lingual (A₂) views. (B) Lower tooth in labial (B₁) and lingual (B₂) views. (C) Lower posterior tooth in labial (C₁) and lingual (C₂) views. (D) Male lower tooth in labial view. (E) Lower symphyseal tooth in labial (E₁) and lingual (E₂) views. (F) Lower tooth in labial (F₁) and lingual (F₂) views. Upper tooth in labial (G₁) and lingual (G₂) views. (H) Upper tooth in labial (H₁) and lingual (H₂) views. (I) Upper tooth in labial (I₁) and lingual (I₂) views. (J) Upper tooth in labial view. (K) Upper tooth in labial (K₁) and lingual (K₂) views. (L) Upper posterior tooth in labial (L₁) and lingual (L₂) views. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

Fourteen partial and complete teeth are referred to the genus Eosqualiolus, a genus of Kitefin Shark which previously contained only a single fossil species from the Eocene of France, and assigned to a new species, Eosqualiolus skrovinai, which is named after Michal Škrovina, described as the first person to encourage Jan Schlogl in to pursue an interest in palaeontology.

Teeth assigned to the species Eosqualiolus skrovinai from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. (A) Lower tooth in labial (A₁) and lingual (A₂) views. (B) Lower tooth in labial (B₁) and lingual (B₂) views. (C) Lower tooth in labial (C₁) and lingual (C₂) views. (D) Lower tooth in labial (D₁) and lingual (D₂) views. (E) Upper tooth in labial (E₁) and lingual (E₂) views. (F) Upper tooth in labial (F₁) and lingual (F₂) views. (G) Upper tooth in labial (G₁) and lingual (G₂) views. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

One, damaged, tooth is assigned to a third Kitefin Shark genus, Squaliodalatias, though not assigned to a species due to its poor condition. Fossils assigned to this genus have previously been found from the Late Cretaceous of Lithuania and the Eocene of France.

Tooth assigned to the genus Squaliodalatias from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. In labial (H₁) and lingual (H₂) views. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

Eight partial and complete teeth are assigned to the genus Etmopterus (Lantern Sharks in the family Etmopteridae), small, deepwater Sharks with light producing organs, found more-or-less globally today. The earliest known Lantern Sharks are from the Eocene of France.

Teeth assigned to the genus Etmopterus from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. (A) Lower tooth in labial (A₁) and lingual (A₂) views. (B) Lower tooth in labial (B₁) and lingual (B₂) views. (C) Lower posterior tooth in labial (C₁) and lingual (C₂) views. (D) Lower tooth in labial (A₁) and lingual (A₂) views. (E) Lower tooth in labial (E₁) and lingual (E₂) views. (F) Lower tooth in labial view. (G) Upper tooth in labial (G₁) and lingual (G₂) views. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

Ten partial and complete teeth are tentatively assigned to the genus Miroscyllium (Rasptooth Dogfish), a second type of Lantern Shark. The genus is previously known from a single modern species from the Pacific and some teeth from the Eocene of France.

Teeth tentatively assigned to the genus Miroscyllium from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. (H) Lower symphyseal tooth in labial (H₁) and lingual (H₂) views. (I) Lower tooth in labial (I₁) and lingual (I₂) views. (J) Lower lateral tooth in labial (J₁) and lingual (J₂) views. (K) Lower tooth in labial (K₁) and lingual (K₂) views. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

Fifty three partial and complete teeth are assigned to the genus Paraetmopterus, an extinct Lantern Shark previously only known from teeth from the Eocene of France, and placed in a new species, Paraetmopterus horvathi, named in honour of Juraj and Tereza Horvath and their children.

Teeth assigned to the species Paraetmopterus horvathi from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. (A) Lower tooth in labial (A₁) and lingual (A₂) views. (B) Lower tooth in labial (B₁)

and lingual (B₂) views. (C) Lower tooth in labial (C₁) and lingual (C₂) views. (D) Lower tooth in labial (D₁) and lingual (D₂) views. (E) Lower tooth in labial (E₁) and lingual (E₂) views. (F) Lower tooth in labial (F₁) and lingual (F₂) views. (G) Upper anterior tooth in labial (G₁) and lingual (G₂) views. (H) Upper tooth in labial (H₁) and lingual (H₂) views. (I) Upper tooth in labial (I₁) and lingual (I₂) views. (J) Upper tooth in labial (J₁) and lingual (J₂) views. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

A single tooth is assigned to the family Somniosidae (Sleeper Sharks), a widespread group of Sharks that first appear in the fossil record in the Late Cretaceous of Germany.

Tooth assigned to the family Somniosidae from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. In labial (K₁) and lingual (K₂) views. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

A single imperfect tooth is referred to the genus Gymnura (Butterfly Rays). Modern Butterfly Rays are typically shallow water species, often found in brackish estuarine waters. The genus has a sparse fossil record, but is known from the Palaeocene of India, spreading around Europe, the Middle East and Africa in the Eocene and reaching the Americas in the Oligocene.

Tooth assigned to the genus Gymnura from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. In occlusal (I₁) and basal (I₂) views. Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

Twenty eight complete and partial teeth are assigned to a new species, Nanocetorhinus tuberculatus, of uncertain affinities, but considered to probably be a Neoselachian (the group that includes all extant Sharks, Skates and Rays). The genus name Nanocetorhinus refers to the similarity of the teeth to those of the planktivorous Shark Cetorhinus (the Basking Shark), though these teeth are much smaller, and the specific name, tuberculatus refers to the ornamentation on the teeth.

Teeth assigned to the species Nanocetorhinus tuberculatus from the Early Miocene Cerová−Lieskové locality. (A) Tooth in labial (A₁) and lingual (A₂) views. (B) Tooth in labial (B₁) and lingual (B₂) views. (C) Tooth in labial (C₁) and lingual (C₂) views. (D) Tooth in labial (D₁) and lingual (D₂) views. (E) Tooth in labial (E₁) and lingual (E₂) views. (F) Tooth in labial (F₁) and lateral (F₂) views. (G) Tooth in labial (G₁) and lingual (G₂) views. (H) Tooth in labial (H₁) and lingual (H₂) views, detail (H₃). Underwood & Schlogl (2012).

While the majority of these Sharks belong either to extant genera or extant families, the assemblage is on the whole closer to the deepwater Sharks of the Eocene than to modern Shark assemblages, suggesting that there has been more turnover in deepwater Shark populations since the Miocene than between the Eocene and the Miocene. One remarkable feature of this assemblage is the small size of all the Sharks present; based upon the available material Underwood & Shlogl estimate that none of the Sharks were more than 40 cm in length, though they do not offer any hypothesis as to why this was the case.