The first Proboscideans (Elephants), appeared in the Palaeocene, and like other herbivorous Mammals of this time are presumed to have been browsers (leaf and fruit eaters). Modern Elephants, in contrast, are primarily grazers (grass eaters). Grasses first appeared in the Cretaceous, but extensive grasslands did not become a distinct ecosystem until the Miocene around 23 million years ago. Early Proboscidians had low-crowned teeth, with few lophids (ridges), consistent with a browsing diet, while modern Elephants have high-crowned teeth with numerous lophids, which offers some protection agianst the abbrasive nature of Grasses. The switch to Grasses as a food possibly occured in the Gomphotheres, which appeared in the Middle Miocene and are thought to have been ancestral to True Elephants. The earliest members of the group were trilophadont (had three ridges on their teeth), while later forms, particularly those thought to be ancestral to True Elephants, were tetralophadont (had four ridges), suggestive of a switch towards a more Grass-based diet.

In a paper published in the journal Scientific Reports on 16 May 2018, Yan Wu of the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Tao Deng, also of the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, and the Center for Excellence in Life and

Paleoenvironmentm, and of the Center for Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Sciences, Yaowu Hu and Jiao Ma, also of the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, and of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xinying Zhou, again of the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, and the Center for Excellence in Life and

Paleoenvironment, Limi Mao of the Key Laboratory of Economic Stratigraphy and Palaeogeography, at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Hanwen Zhang of the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol, and of the Earth Sciences Department at the Natural History Museum, Jie Ye, again of the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, and Shi-Qi Wang, once again of the Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, and the Center for Excellence in Life and

Paleoenvironmentm, and of the Center for Excellence in Tibetan Plateau Earth Sciences, examine the diets of two species of Middle Miocene trilophadont Gomphotheriid Proboscideans, by examining phytoliths (silica fragments produced by plants) preserved in dental calculus of six specimens from the Miocene Halamagai Formation in the northern Junggar Basin of Xinjiang Province, China.

The Middle Miocene deposits of the Junggar Basin produce a diverse range of Gomphotheriid specimens, accompanied by floral remains indicative of a largely forested environment. Late Miocene strata from the same area, in contrast, have a much less diverse Gomphotheriid fauna, dominated by a few tetralophadont forms, and a more arid, Grass-dominated environment, suggesting that this area may have played an important role in the switch between browsing and grazing behaviour in early Proboscideans.

Wu et al. examined calculus from four specimens of Gomphotherium connexum and two specimens of Gomphotherium steinheimense. Gomphotherium steinheimense is thought to have been closely related to the early tetralophadont Gomphotheriid Tetralophodon longirostris, while Gomphotherium connexum is a more distant relative.

Of the phytoliths obtained from the calculus of Gomphotherium connexum, between 40% and 50% were identified as having originated from Grasses, whereas between 28% and 34% could be identified as having come from broadleaved plants. This would at first seem to imply a diet with a high proportion of Grasses, but Grasses produce a far greater amount of phytoliths than broadleaved plants (hence their more abrasive nature), so this probably indicates a diet with a high proportion of broadleaved plants. In contrast about 85% of the phytolihs from the calculus of Gomphotherium steinheimense could be identified as having come from grasses, indicative of a much more Grass-based diet.

See also...

The Middle Miocene deposits of the Junggar Basin produce a diverse range of Gomphotheriid specimens, accompanied by floral remains indicative of a largely forested environment. Late Miocene strata from the same area, in contrast, have a much less diverse Gomphotheriid fauna, dominated by a few tetralophadont forms, and a more arid, Grass-dominated environment, suggesting that this area may have played an important role in the switch between browsing and grazing behaviour in early Proboscideans.

Wu et al. examined calculus from four specimens of Gomphotherium connexum and two specimens of Gomphotherium steinheimense. Gomphotherium steinheimense is thought to have been closely related to the early tetralophadont Gomphotheriid Tetralophodon longirostris, while Gomphotherium connexum is a more distant relative.

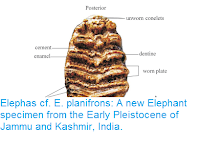

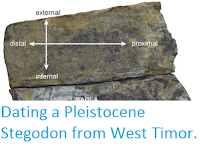

Geography, geology, and phylogeny in relation to the study material. (A) The location of the study area (black star). The map was generated by GTOPO309 using Globalmapper (v10). (B) Stratigraphic column and polarity with palaeomagnetic age, also denoting the horizon of study material in the strata (in light yellow). (C) The 50% majority consensus tree from 29 maximum parsimonious trees showing the phylogenetic position of the Gomphotherium species and Tetralophodon longirostris, the number at each node representing the support value calculated by majority rules (percentages of supported MPTs in the total MPTs, which are always larger than 50%) and the orange frame indicating the sister-taxon relationship of Gomphotherium steinheimense and Tetralophodon longirostris. (D) Gomphotherium steinheimense, right m3. (E) Gomphotherium connexum, left M3. Wu et al. (2018).

Of the phytoliths obtained from the calculus of Gomphotherium connexum, between 40% and 50% were identified as having originated from Grasses, whereas between 28% and 34% could be identified as having come from broadleaved plants. This would at first seem to imply a diet with a high proportion of Grasses, but Grasses produce a far greater amount of phytoliths than broadleaved plants (hence their more abrasive nature), so this probably indicates a diet with a high proportion of broadleaved plants. In contrast about 85% of the phytolihs from the calculus of Gomphotherium steinheimense could be identified as having come from grasses, indicative of a much more Grass-based diet.

See also...

Follow Scieny Thoughts on Facebook.