The Ornithopod Dinosaur Tenontosaurus tilletti is known from about 80 skeletons and partial skeletons, recovered from the Early Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Wyoming and Montana. Slightly older skeletons from other sites in the American Midwest have been assigned to a second species of Tenontosaurus, Tenontosaurus dossi. The Cloverly Formation also produces a variety of other Dinosaur skeletons, including Ankylosaurs, Sauropods, Ornithomimids, Hypsilophodonts, and Dromaeosaurids, as well as Turtles, Frogs, Crocodiles, and Triconodont Mammals.

In a paper published in the journal Cretaceous Research on 11 August 2022, John Nudds and Dean Lomax of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, at the University of Manchester, and the late Jonathan Tennant, formerly of the Institute for Globally Distributed Open Research and Education, describe some material associated with a specimen of Tenontosaurus tilletti obtained from the Cloverly Formation in Montana, and currently in the collection of the University of Manchester Museum.

The specimen, MANCH LL.1227, was found on the Kelly Ranch in Wheatland County, Montana, by rancher Robert Kelly in 1994, and obtained for the Manchester Museum by John Nudds in 1999, where it became the centrepiece of the (then) newly refurbished Fossil Gallery. The fossil was prepared and mounted, and came with what were described as 'gastroliths' and 'Cycad seeds' found in the stomach region, and two 'Deinonychus teeth' found associated with a cervical vertebrae, and was described as having arthritis in one hand. The specimen was replaced as the centrepiece of the gallery in 2004, when it was replaced with a cast of a Tyrannosaurus skeleton, and placed into storage. The specimen was later studied by Jonathan Tennant, and fully described as a Master's Thesis, published on the arXiv database.

The specimen has been disassembled, although parts of it remain attached to the metal frame upon which it was displayed. Some parts of the skeleton have been modified, mostly by the addition of plaster sections to make up for missing bones or portions of bones. Many of the more slender bones of the skeleton are broken, some beyond repair, while others, such as the ossified tendons, are missing. The whole was painted with a coloured varnish, which has now been removed. The museum intends to reconserve the skeleton for inclusion in a future display.

Various associated materials were obtained along with the skeleton. These include twelve stones identified as gastroliths and two spherical objects identified as Cycad seeds which were found in the gut region of the skeleton, as well as two Theropod teeth, identified as Deinonychus antirrhopus, which were associated with the cervical vertebrae, and a sample of the sediment in which the fossil was buried, identified as volcanic ash.

Gastroliths (MANCH LL. 12278a-l) found in the gastric region of MANCH LL.12275. Scale bar is 3 cm. Nudds et al. (2022).

Gastroliths (MANCH LL. 12278a-l) found in the gastric region of MANCH LL.12275. Scale bar is 3 cm. Nudds et al. (2022).The gastroliths, if correctly identified, would lend support to the theory that early-branching Ornithopods, such as Tenontosaurus tilletti, lacked the chewing capacity of later branching forms such as Hadrosaurs. Gastroliths have been found in three Orinithopod specimens to date, all of which were early-branching forms, namely Gasparinisaura cincosaltensis, from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina, Haya griva, from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia, and Changmiania liaoningensis, from the Early Cretaceous of China. Possible gastroliths have also been reported from Notohypsilophodon comodorensis, also from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina. Therefore, if the pebbles associated with MANCH LL.12275 are in fact gastroliths, then they are the second oldest known example of such in an Ornithopod. The specimen came with a (less than perfect) photograph of the stones in place within its body cavity, and with no other such pebbles visible elsewhere. Furthermore, the specimen was buried within a fine-grained matrix, from which such pebbles are unlikely to have been derived, and within which any pebbles present are unlikely to have been preferentially sorted to form an accumulation. On the basis of this, Nudds et al. conclude that, while they cannot completely rule out another origin, the most likely explanation for the pebbles is that they were in fact gastoliths.

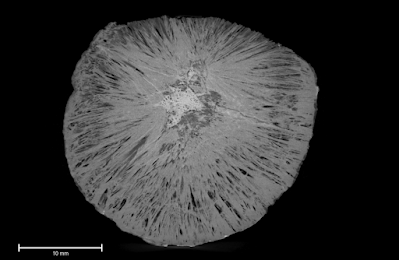

Also found within the body cavity of MANCH LL.12275 were two spherical objects interpreted as Cycad seeds. These were subjected to computerised tomographic scanning, which revealed that they have an irregular amorphous core, surrounded by an outer radial structure, quite different from the structure of Cycad seeds.

While the structure of these objects rules out a Cycad origin, it is consistent with their being derived from a member of the Bennettitales, an extinct order of Gymnosperms, which produced cones with a radial structure similar to that seen on the spherical structures. Notably, the structures are very similar to cones of the Bennettitalean Williamsonia from the Late Cretaceous of Vancouver Island.

However, further examinations made by cutting one of the structures into thin sections revealed that the core is composed of iron oxyhydroxides (goethite/limonite), and the outer radial structures are probably the highly insoluble baryte with a feathery texture. Such a composition is highly unlikely to have derived from any plant source, but rather probably formed as the skeleton was exhumed, and nodules of pyrite or marcasite, which nucleated around some form of decaying organic matter as the specimen was first buried, were exposed to oxidising conditions. Under such circumstances these iron minerals will oxidise to goethite/limonite, with iron sulphites and barium ions dissolved within pore fluids being extruded and forming baryte. Thus the structures are thought likely to be of entirely mineral origin, and not informative about the diet of the living Animal.

Two teeth were found associated with one of the cervical vertebrae of MANCH LL.12275, and identified as belonging to the Therapod Dinosaur Deinonychus antirrhopus. One of these teeth has subsequently been lost. The presence of these teeth in association with a skeleton of Tenontosaurus tilletti would appear to be a rare example of a direct predator-prey interaction, something seldom seen in Dinosaurs. Curiously, remains of Deinonychus antirrhopus and Tenontosaurus tilletti are quite often found in association, while Tenontosaurus tilletti remains have never been found in association with even fragmentary remains (such as shed teeth) of other predators known to have been present in the Cloverly ecosystem, such as Crocodiles. The reasons for this are unclear, though the association of two Deinonychus antirrhopus teeth with MANCH LL.12275 does suggest that at least one of these Theropods (it is thought possible that Deinonychus may have hunted in packs) was feeding upon the carcass of this Dinosaur before it was burried.

The sediment layer from which MANCH LL. 12277 was excavated was identified by its discoverers as volcanic ash. However, analysis of the sediment supplied with the specimen found that it was 87% calcium carbonate and 7% silica, with any potentially ash-derived minerals being present only at trace levels. This is unsurprising for the Cleverly Formation, where ash inclusions are rare.

Determining the way in which extinct prehistoric Animals behaved in life is one of the greatest problems faced by palaeontologists. For the most part, this must be done entirely by analysis of the morphology of the fossils these Animals leave behind, but on rare occasions, it is possible to recover direct evidence of interactions from fossils.

MANCH LL. 12277 is one of the most complete Tenontosaurus tilletti specimens known, and was initially interpreted as providing several lines of evidence about the world that it lived in and how it interacted with that world. The specimen was originally reported to have been found buried in a volcanic ash matrix, neither of these turned out to be true, with the specimen found to be buried in a limestone sand, while the 'Cycad seeds' were found to be diagenetic features of non-biological origin.

However, the teeth found associated with the skeleton do appear to be evidence of a trophic relationship (i.e. one organism feeding on another), while the presence of gastroliths within the body cavity of the specimen is a new discovery for this species (albeit not an unexpected one), and provides us with insight into this Dinosaurs diet and feeding habits.

See also...

Online courses in Palaeontology.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Twitter.