Walled oases appear to have been a key part of the development of early settled societies on the Arabian Peninsula. Unlike other defensive systems, such as isolated towers, fortresses, or even walled cities, walled oases comprised an extensive system of defences enclosing an entire agricultural system, and marking a boundary between this managed farmland and the surrounding desert. Two such walled oases, Tayma and Qurayyah, have been familiar to archaeologists for a long time, and been the subject of numerous studies. However, recent examination of satellite images of the region has exposed a series of previously unknown walls around other oases, including Khaybar, Huwayyit, Dumat al-Jandal, Hait, Al-Wadi, Al-Ayn, and al-Tibq. This process of urbanization and oasis protection appears to have begun during the Bronze Age and persisted into the Iron Age, paying a major role in the appearance of the caravan kingdoms.

Khaybar has a pre-Islamic period fortress located on a mesa at the centre of the great wadis which dominate the site, but a wall enclosing the entire oasis had not previously been observed or even suspected. The walls are spread over a wide area, and for the most part have been dismantled to the point at which they are hard to recognise. The area is rugged, and made up largely of basalt rock with almost zero sedimentation, so that any and all archaeological remains sit on the surface. This has created a lunar landscape, dotted with archaeological remains from a wide range of periods, including desert kites, mustatils, funerary avenues and dense necropolises, encampments, forts, plot walls, a range of less identifiable structures. To date, about 16 000 such structures have been counted within the 56 km² of land which constitutes the oasis. Determining that dismantled and fragmentary walls scattered over a wide area formed part of a single original structure requires extensive fieldwork and careful examination of the components.

In a paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports on 10 January 2024, Guillaume Charloux, Shadi Shabo, Guillaume Chung-To, and Bruno Depreux of the French National Centre for Scientific Research, independent researcher François Guermont, Kévin Guadagnini, also of the French National Centre for Scientific Research, Thomas Therasse and Mylène Bussy, also independent researchers, Saifa Alshilali of the Royal Commission for AlUla, Diaa Albukaai and Rémy Crassard, again of the French National Centre for Scientific Research, and Munirah AlMushawh, another independent researcher, demonstrate the presence of a defence wall around the entire Khaybar Oasis, as well as providing dating information on its construction and use.

Location map of the Khaybar walled oasis (red and white circle) and other major sites in north-western Arabia. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

Six seasons of fieldwork were carried out between October 2020 and March 2023, as part of the Khaybar Longue Durée Archaeological Project. Khaybar is about 670 m above sealevel, and is located in the Hijaz Region of Saudi Arabia, between Medina and AlUla. It was an important agricultural centre in the Early Islamic Period, with the entire oasis measuring about 8 km by 7 km. The oasis is at the confluence of three alluvial valleys, Wadi al-Suwayr/Halhal, Wadi al-Zaidiyyah, and Wadi al-Sulamah, which merge on the western side of the oasis to form the Wadi Khaybar. The wadis are cut into the surrounding Neogene-Quaternary basalt plateau, and contain a series of perched sediment beds. The first (brief) archaeological survey of the oasis was carried out in 2015. This was followed by an aerial survey by the Aerial Archaeology in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia project in 2018, with the Khaybar Longue Durée Archaeological Project beginning in 2020.

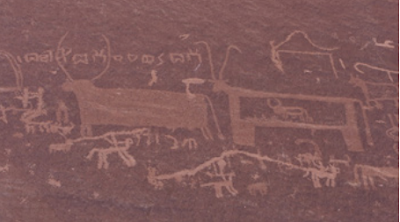

Aerial views of the dry-stone basement of the outer rampart: (A) Segment KH00911 facing south; (B) Segment KH01130 facing north; (C) Segments KH00904-KH00905 and KH00906 facing south; (D) segment KH00922. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

Charloux et al. used ArcGIS mapping software to combine aerial photography with high resolution geological maps and e architectural, archaeological and geomorphological surveys of the oasis to build up a map of the wall network. They also dug 19 test pits into sections of the remaining ramparts.

Map of the main ramparts of Khaybar, with identification of main segment walls and location of bastions and soundings in 2021–2023. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

Charloux et al. discovered 5.9 km of previously unknown wall, 5.9 km of which are interpreted as being part of a network which once enclosed the entire oasis. There were 146 large wall segments remaining, ranging in length from a few metres to several hundred metres. The discovered walls were placed into five groups. Group A comprised aligned accretion walls 2.4-4.5 m thick, with both bastions and towers, and without any obvious discontinuity, which formed part of the enclosure surrounding the al-Natah Site. Group B walls comprised two exterior faces with a rubble in-fill, 1.4-2.4 m thick, with bastions, forming part of an inner enclosure wall. Group C walls were similar to Group B walls, but formed part of the outer perimeter enclosing the entire oasis. Group D walls are made from multiple types of masonry, are between 50 cm and 4 m thick, lack bastions, and again form part of an inner enclosure. Group E walls were smaller segments, similar in construction to Group D walls, which did not form part of any obvious larger structure.

View of the ramparts KH00905-KH00906 and a bastion KH00974 during excavation, looking west. Kévin Guadagnini in Charloux et al. (2024).

The remaining outer wall around the Khaybar oasis has a length of 5912.78 m, which is thought to represent 41% of an original wall which would have measured 14.5 km, enclosing an area of 11.8 km². The wall is interrupted by a variety of newer roads, buildings, gardens, etc., making it difficult to reconstruct the entire shape of the perimeter boundary, particularly on the southern side.

Rampart KH00909, looking north. Charloux et al. (2024).

Seventy four bastions are still present on this outer wall, wall facing out towards the desert rather than in towards the oasis, which Charloux et al. consider to be strong evidence for the entire enclosure to have been built in a single phase of construction, albeit one which would have taken some time and been subject to subsequent additions and alterations.

Rampart KH00911 situated on the crest (right on the picture), looking east. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

The walls of the outer perimeter are also very similar throughout their extent, most being rubble-filled, double-faced dry-stone walls, between 1.8 m and 2.4 m thick, which again supports a single interval of wall building. The walls appear to have been built in separate segments, with the thinnest section on the slopes and summits of Jabal Mushaqqar, where it is only 1.1 m thick and built of simple drystone masonry, which was apparently acceptable to the builders for this s high position along a ridge on the top of a rhyolite mountain. Earlier stone structures in the region appear to have been raided extensively for building stone.

View of the currently preserved masonry of the outer enclosure wall (rampart KH01130) facing north. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

The majority of the wall is made up of curvilinear sections which for the most part follow the contours of the plateau, with connections between these long sections crossing valleys at their narrowest points. Ramparts are between 120 m and 250 m from the cliff edge, apparently built at this distance to avoid the topological irregularities associated with the cliff. Building the wall in this way would have given good visibility over both the oasis and the surrounding desert, while enclosing the minimum amount without encroaching on the agricultural land.

Rampart KH00911 on top of the cliff, looking north. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

The height of the original walls is impossible to determine; only the stone bases of the walls remain, but there are traces of mud bricks in places, which suggests a brick superstructure existed on top of the stone wall. The highest remaining section of wall is 3 m tall, at Makidah on the southern section. Charloux et al. suggest another 2 m of brick wall may have existed on top of this, possibly with a walkway. The walls at the Tayma Oasis, have been estimated at 6 m high, with an inner enclosure which might have been 14 m high, while the walls at Dumat al-Jandal have been estimated at 6.5 m, and a section of walkway has been identified.

Rampart KH00919, with dismantled infilling, looking northeast. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

There are no contemporaneous structures attached to the outer wall, which is made of basalt and has been heavily eroded by the desert winds and runoff from the annual rains, as well as depletion due to raiding by later builders of other structures, all of which tend to make dating of any structure difficult. However, the wall is built over several older pendant tombs, some of which were also raided for stone by the wall builders. These tombs have been dated to the middle of the third millennium BC, which makes it impossible for the wall to have been built before about 2600-2200 BC.

Rampart KH00918, looking northeast. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

Charloux et al. were able to obtain radiocarbon dates from eight charcoal samples obtained from five test pits sunk into the remaining wall segments. The oldest of these come from beneath the wall, providing a maximum age for the overlying wall segment. Other samples come from layers abutting the rampart or in the immediate vicinity of its foundation, suggesting they provide a time for the construction or first use of the wall, while other pieces come from the wall infill, which again makes it most likely they date from the time of wall construction. Finally, sone charcoal pieces come from beneath what appear to be gates in the wall, and could therefore have been deposited while the wall was in use.

Rampart KH00918, looking southwest. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

Based upon these radiocarbon dates, Charloux et al. suggest that the outer perimeter wall at Khaybar Oasis was built after 2279 BC, and probably after 2139 BC, but probably before 2201 BC and definitely before 1980 BC. The wall appears to have still been in use as late as 1741 BC and 1542 BC.

Location of dating samples on rampart KH00905 (plan on orthophotography and sections). Section 1: KH00906.002 and KH00906.004 are filling layers above ash area KH00906.005 on top of construction floor KH00906.006; Section 2: KH00905.002 is a collapse layer above a thin ash dump above fills KH00905.003 and KH00905.005 above possible construction floor KH00905.004. Guillaume Charloux, François Guermont & Kévin Guadagnini in Charloux et al. (2024).

This suggests that the Khaybar Oasis, one of the largest in Arabia, was enclosed by a perimeter wall in the Bronze Age, around 2000 BC. The appearance of such walled oases is thought to have been a key step in the evolution of urbanization in the region. The walls presumably offered protection against raids from the desert, a danger to settlements on the Arabian Peninsula in the pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Periods, but one for which evidence has been absent in the Bronze Age until now, despite the presence of Bronze Age 'Warrior Burials' in northern Arabia. Such walls may have also plaid a role in controlling the environment within the oasis, helping to prevent soils from blowing away and helping to prevent flash floods from reaching crops. The walls would also have made a symbolic statement about the ownership of the oasis, clearly delimiting a boundary between the territory inside the wall and the open desert. This would have been a powerful symbol to any desert groups seeing it, and presented a clear social identity to those within.

Dismantled bastion at the front of rampart KH00918, looking southwest. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

The size of the surrounding wall suggests that a reasonably large workforce was involved, and that local political leadership was sufficiently organized to co-ordinate such a project. It has previously been assumed that large building works like this in Bronze Age societies would have required very large numbers of workers, but recent evaluations of workloads has suggested that much smaller numbers of people might have been able to undertake large projects. Constructing the outer wall to a height of 5 m would have required the movement of 164 000 m³ of stone, and/or bricks, which Charloux et al. would have required 170 000 working days. Whilst this seems a lot, a community of 500 people, in which half of the population could spend six months of each year on the project, would have been able to construct the outer wall in four years. Had half the population been able to work on the project full time, then only two years would be needed to construct the wall. Furthermore, while some degree of planning would no doubt have been needed to complete the project, many of the choices which would have had to be made are not complicated, so a large bureaucracy was probably not needed, again suggesting the task was within the grasp of a relatively small community.

Test pit in gate KH09039 on rampart KH01130 (plan on orthophotography and section), with location of dated samples. Outside the gate, KH09039.004 is a small layer of brown gravel laying directly on the substratum below the stone collapse. Inside the gate, the collapse was underlain by KH09039.009, an occupation level consisting of grey, coarse sandy sediment with some charcoal and animal bones. Below, a layer of brown gravel (KH09039.010) was laying on the bedrock. Guillaume Charloux, François Guermont & Kévin Guadagnini in Charloux et al. (2024).

Pastoralists from northwest Arabia, where local communities were already building walled and fortified settlements on the fringes of the desert in what is now southern Lebanon and Syria, are thought to have settled at Khaybar Oasis during the Early Bronze Age, building avenues of monumental funerary structures, as at other oasis in the region, and on the trails between them. The skill set needed to build these large funerary structures is not greatly different from the one that would have been needed to construct fortified ramparts around an oasis, so the construction of avenues of funerary monuments hay have been the first stage in a transition from a pastoralist, nomadic existence to a more settled farming one where strategic territories with good water supplies were enclosed and defended. The nature of such projects would have favoured the development of a more hierarchical society, leading in time to the development of more formal urban centres. This settling and enclosing of the oases may have been linked to a drying climate, which would have made wandering pastoralism more precarious and reliable sources of water more precious, although the history of the climate in the region is not well enough understood to make firm assertions about this.

Rampart KH01130, looking north. Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

Ramparts appear to have been erected around the entire oasis between about 2250 BC and 1950 BC, making these fortifications younger than the ones at Qurayyah, which were constructed in the first half of the third millennium BC, or and those at Tayma, built in the second half of the third millenium BC, but older than the Iron Age fortifications at Dûmat al-Jandal. This is interesting, as it shows a repeated process of oasis enclosure at different sites, over a lengthy period of time. Understanding why this happened would be a significant step in understanding the development of Bronze Age and Iron Age societies in Arabia, and the trajectory of urbanization followed there.

Reconstruction view of the northern part of walled oasis of Khaybar around 2000 BCE. Pending the results of definitive archaeobotanical analyses, the Plant cover at this stage is based on the identified species (Acacia, Tamarisk, Amaranth, cereals). Mylène Bussy & Guillaume Charloux in Charloux et al. (2024).

Charloux et al.'s field surveys and archaeological excavations have demonstrated that the Khaybar Oasis in Northwest Arabia was once enclosed by an immense surrounding wall, similar to that seen around other oases in the region. This dates from the late third millennium BC, and was probably constructed by a local pastoralist community settling and claiming the oasis as their territory. The walls appear to have remained in use for several centuries, before being partially dismantled and replaced with other structures. This marks out the oasis as an important stage in the development of urbanized communities in the region, and key part of the heritage of Arabia.

See also...

%20(1)%20(1).png)