70 Viriginis is a G-type Yellow Dwarf Star about 59 light years from Earth in the constellation of Virgo. It is

calculated to have a mass 109% of that of the Sun, but radius 194% of the

Sun’s, and a lower temperature, 5393K, compared to 5778K for the Sun, from

which it is calculated to be somewhat older, approximately 7.77 billion years

(compared to about 5.0 for the Sun). This star hosts one of the first

discovered exoplanets, 70 Virginis b, asuperjovian planet in a short (116 days)

but highly eccentric orbit discovered in 1996.

In a paper published on the arXiv database at Cornell University

Library on 15 April 2015 and submitted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal, Stephen Kane of the Department of Physics & Astronomy at San Francisco State University, Tabetha Boyejian of the Departmentof Astronomy at Yale University, Gregory Henry of the Center of Excellence in

Information Systems at Tennessee State University, Katherina Feng of the Departmentof Astronomy and Astrophysics and Center for Exoplanets & Habitable Worlds

at Pennsylvania State University and the Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Natalie Hinkal, also

of the Department of Physics & Astronomy at San Francisco State University,

Debra Fischer, also of the Department of Astronomy at Yale University, Kaspar

von Braun of Lowell Observatory, Andrew Howard of the Institute for Astronomy

at the University of Hawaii and Jason Wright, also of the Department

of Astronomy and Astrophysics and Center for Exoplanets & Habitable Worlds

at Pennsylvania State University, present a fresh study of the 70 Virginis

system using new data from the Cente rfor High Angular Resolution Astronomy

(CHARA array) at Georgia State University and the HIRES echelle spectrometer on

the 10.0m Keck I telescope, which they combine with previously acquired data on

the system from the Hamilton Echelle Spectrograph on the 3.0m Shane Telescope at Lick Observatory and the ELODIE spectrograph on the 1.93m telescope at Observatoirede Haute-Provence, which they use to build a model of the Habitable Zone of the

system, and calculate the possibility of an Earth-sized planet remaining in a

stable orbit within it.

Kane et al. derive a

‘conservative’ habitable zone for the 70 Virginis system with an inner boundary

at 1.63 AU from the star (i.e. 1.63 times the average distance at which the

Earth orbits the Sun) and an outer boundary at 2.92 AU from the star, and an

‘optimistic’ habitable zone with an inner boundary at 1.29 AU and an outer

boundary at 3.08 AU.

A top-down view of the 70 Virginissystem showing the

extent of the Habitable Zone calculated using the stellar parameters established

with the CHARA, HIRES, Hamilton Echelle and ELODIE data. The conservative Habitable

Zone is shown as light-gray and optimistic extension to the Habitable Zone is

shown as dark-gray. The revised Keplerian orbit of the known planet is overlaid

as a continuous dark line. Kane et al. (2015).

Next Kane et al. attempted

to calculate the possibility of an Earth-sized planet remaining in a stable

orbit within this habitable zone. In order to do this they calculated the

stability of planets at the inner and outer margins of the conservative and

optimistic Habitable Zones (i.e. 1.29 AU, 1.63 AU, 2.92 AU and 3.08 AU), since

if these orbits are stable then intermediate orbits, fully within the Habitable

Zone, ought to be available.

These calculations revealed that while it was possible for an

Earth-sized planet to remain in a stable orbit within the habitable zone, the

gravitational influence of the known planet, 70 Virginis b, would make it impossible

for such a planet to remain in a stable orbit in the same orbital plane as the

larger body. This is problematic if we consider the Solar System to be a

typical planetary system, as all the planets in the Solar System orbit in

approximately the same plane, and models of Solar System formation suggest that

this was the way in which they formed, apparently ruling out other

configurations. However other stellar systems have been discovered in which not

all the planets orbit in the same plane, indicating that such an outcome is not

impossible.

Kane et al. calculate that

an Earth-sized planet orbiting 70 Virginis at a distance of 1.29 AU would need

to have an orbit tilted at an angle of at least 24˚ to that of 70 Virginis b to

remain stable. Such a planet at 1.63 AU would need to be tilted at 25˚ to

remain stable, one at 2.92 at 10˚ and one at 3.08 AU at 3˚. This is roughly

linear, with hypothetical planets further from 70 Virginis b able to adopt less

inclined orbits due to the reduced influence of its gravity, though the planet

at 1.63 was more affected than that at 1.29 AU, due to its being closer to

being in a resonant orbit (planets in resonant orbits pass one-another

regularly on their orbital cycle, typically with the inner planet completing

two orbits for one of the outer planet or some similar arrangement; such

resonant orbital arrangements are extremely stable, but orbits close to

resonant arrangements are highly unstable, with the smaller body typically

being either pushed into the stable arrangement or ejected from the system

completely).

See also…

The Kepler Space Telescope has discovered over 4000 candidate

planets, around 40% of which are in systems with multiple planets. Many of the

early multiple planet systems discovered contained one or more...

The Kepler Space Telescope observed a 115 square degree of space for

four years (from May 2009 till May 2013), looking for potential planets around

the 150 000 stars in the magnitude range 8-16 within the field. In this time it

found a total of 4233 candidate planets, of which 965 have subsequently been

confirmed. The conformation of such a planet requires follow...

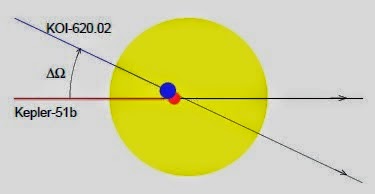

Conformation of the third planet in the Kepler-51 System. Kepler-51 is a G-type Yellow Dwarf star 2800 light years from Earth in

the constellation of Cygnus. It has a...

Conformation of the third planet in the Kepler-51 System. Kepler-51 is a G-type Yellow Dwarf star 2800 light years from Earth in

the constellation of Cygnus. It has a...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.