Rapa Iti, the southernmost inhabitable island in French Polynesia, is a volcanic caldera with a subtropical climate and a surface area of 38 km² and a highest point 650 m above sealevel, lying within the Austral Islands, a group of eight volcanic islands to the south of the Society Islands. It is thought to have been reached by Polynesian settlers between 1100 and 1200 AD, with the first Europeans arriving in 1791. Before these events, the island's ecology was dominated by Birds, with no native Mammals or terrestrial Reptiles. Today, little of this original Birdlife remains. The Rapa Fruitdove, Ptilonopus huttoni, still remains, but is Critically Endangered, while the Rapa Shearwater, Puffinus myrtae, is now found only on offshore islets.

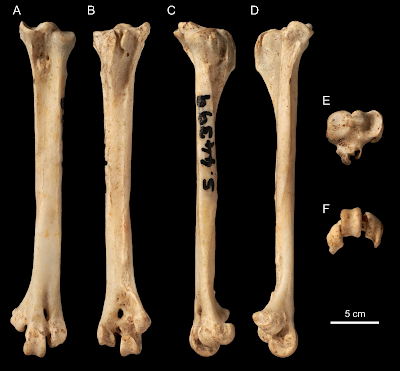

The remainder of Rapa Iti's indigenous Birdlife is known only from archaeological remains. One such is a left tarsometatarsus discovered during an archaeological dig in Tangarutu Cave on Rapa Iti, by Alan Tennyson of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and Atholl Anderson of the Department of Archaeology and Natural History at the Australian National University, and initially described by them as a 'Gallirallus-type Rail'.

In a paper published in the journal Taxonomy on 20 December 2021, Rodrigo Salvador, also of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, along with Atholl Anderson and Alan Tennyson, formally describes the tarsometatarsus as that of a new, previously unknown, species of extinct Rail.

The new species is named Gallirallus astolfoi, in reference to Astolfo, a fictional paladin in the Italian epic poem Orlando Furioso, who was banished to a remote island by the sorceress Alcina. The tarsometatarsus is identified as that as a member of the Family Rallidae within the Order Gruiformes by the presence of two open tendinal canals, one distal foramen, and the tendinal bridge. It is assigned to the genus Gallirallus on the basis of a corpus tarsometatarsi much wider than it is deep, an unenclosed medial sulcus hypotarsi, a fossa parahypotarsalis medialis shallow at the proximal end, a short, shallow fossa metatarsi I, a crista plantaris mediana which slopes gradually to the hypotarsus, a trochlea metatarsi tertii which is sloped toward medial trochlea at its distal end, and a cotyla medialis with a rectangular proximal aspect with a flat dorsal margin.

The tarsometatarsus is identified as that of a new species because it is considerably smaller than that of other members of the genus Gallirallus, with a proportionately much narrower and shallower shaft, giving it a more delicate appearance.

Gallirallus astolfoi is the fourth species of extinct Bird from Rapa Iti, a pattern repeated across the Pacific, where many species of indigenous Birds, and in particular Rails, became extinct after Humans, and Human associated Animals. In French Polynesia these losses have been linked to predation of adult Birds, eggs, and nestlings by Humans, Rats, and Cats, and to environmental modification by Humans and Goats. On Rapa Iti Rats are known to have arrived with Polynesian settlers, while Europeans brought with them Cats, Goats, Cattle, Pigs, and Dogs.

The single remaining bone of Gallirallus astolfoi is insufficient to tell if the species was hunted by Humans, but the fact that it was found in a cave that was inhabited by Humans, alongside Fish remains that were almost certainly brought there by Humans for consumption, and the remains of six other species of Birds, makes it highly likely that this was the case.

The fact that Gallirallus astolfoi was smaller than flying members of the genus, and found on a remote island, makes it highly likely that the species was flightless, something very common in Rails (only two of the 30 or so described species of Gallirallus are widespread, flying, Birds, the remainder are flightless and endemic to islands).

See also...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Twitter.