Since the 1980s an increasing body of material has been assigned to cultural expression by the Neanderthal people, although symbolic material produced by Neanderthal artists remains extremely rare. This material includes a number of carved bones and rocks, a variety of modified shells, and a selection of feathers and Raptor claws apparently modified for use as personal ornamentation. A number of pigments are known to have been used by Neanderthals, although these potentially have other uses than pigmentation, making their purpose hard to assess. Other artefacts are less easy to interpret, such as the 'Mask of la Roche-Cotard', thought to be about 75 000-years-old, a piece of flint which may have been shaped to resemble a face, with a bone pushed through in a way that might represent eyes, or the Bruniquel Cave construction, where, in a large chamber located more than 300 meters from the entrance, many stalagmites have been deliberately broken and placed on the ground to form a large oval structure, around 170 000 years ago. A variety of other symbolic behaviours are associated with Neanderthals, including ritual burials, although many of these are difficult to interpret. What is clear, however, is that Neanderthals did engage in symbolic behaviour, and that the expression of this changed considerably over time.

A variety of engraved markings, clearly different to functional cut marks, have been found on rocks, bones, shells, and other items from Middle Palaeolithic sites in Europe and the Middle East. The engraved phalanx of a Giant Deer has been found at an archaeological site Einhornhoehle in Germany, in a level dated to more than 47 000 years ago. A phalanx and eight talons of an Eagle, with cut marks, evidence of burning, and traces of ochre, alongside Mousterian tools, and Neanderthal bones was found at Krapina I in Croatia. (the Mousterian industry is closely associated with Neanderthals in Europe, where it appeared about 160 000 years ago and vanished about 40 000 years ago). One of the Neanderthal bones at Krapina I, a frontal (forehead) has 35 cut marks upon it. A set of Bird bones from Fumane Cave in Italy, dated to between 44 800 and 42 200 years ago show signs of having been cut with a flint blade in a way intended to facilitate the intact removal of large feathers, while in the same cave a fossil shell covered with ochre was recovered from a Mousterian layer. At the Zaskalnaya VI Neanderthal site in eastern Crimea a Raven bone was found with a series of parallel, equidistant notches cut along its main axis. The Los Aviones Mousterian Site, in the Murcia region of southern Spain, has produced marine shells modified in several ways, including shells with perforated umbos and shells showing signs of having been coloured with haematite. Other artificially coloured shells have been found at Anton Cave, also in Murcia. At Quneitra in the Golan Heights, where Neanderthals and Modern Humans are thought to have had a long period of co-existence, a Levallois flint core, 8 cm in length has been found which has been engraved with a pattern of straight parallel lines and semi-circular concentric lines, which are apparently entirely decorative in function. At Gorham’s cave, Gibraltar, a layer containing Mousterian material covered a cave floor carved with geometric designs. The Ardales, Maltravieso and La Pasiega sites, all in Spain, all have markings made on cave walls with a red pigment, which are overlain by a calcite flowstone cement, from which uranium-thorium dates have been obtained which imply Neanderthal artists. However, this has been disputed, dates being a common problem with material thought to be of Neanderthal origins, with most of the material described being identified as Neanderthal by its association with Mousterian tools rather than directly dated.

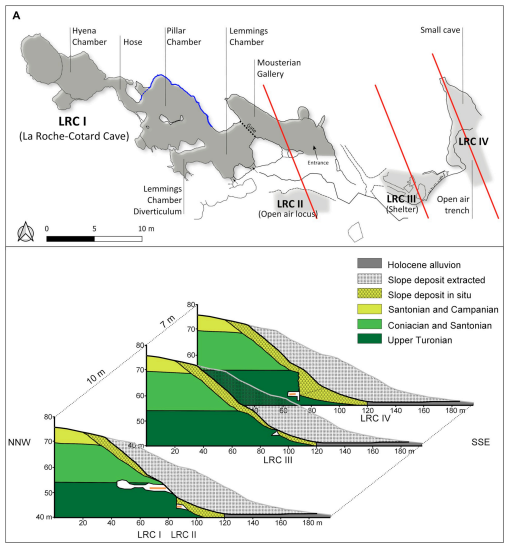

The La Roche-Cotard Cave in central France was revealed by quarrying in 1846, and excavated by the then owner of the site, François d’Achon in 1912, revealing a number of Mousterian artefacts. Subsequent excavations in the 1970s and from 2008 onwards, have found three additional archaeological sites close to this cave. The sites are numbered in the order they were discovered, with the original cave been LRC I, an open air site at the foot of a nearby cliff being LRC II (which produced the 'Mask of la Roche-Cotard'), a small rockshelter being LRC III, and a smaller cave and associated trench being LRC IV. All of these sites have produced Moustrian artefacts, apart from LRC II, which produced only the enigmatic 'Mask'.

During the 1970s and modern campaigns it was observed that the walls of cave LRC I are marked by finger flutings (gouges into soft rock made with fingers), and in places spotted with red ochre. The walls also have a range of other markings, including scratch marks attributed to Animal claws, smooth patches thought to have been cause by rubbing, again probably by an Animal, percussion marks left by metal tools, presumably in 1912, and a single piece of graffiti, known to date from 1992.

In a paper published in the journal PLoS One on 21 June 2023, a team of scientists led by Jean-Claude Marquet of the Laboratoire Archéologie etTerritoires and GéoHydrosytèmes COntinentaux at the Université de Tours, formally describe the fingermarks in the LRC 1 cave as intentional engravings, and provide dating evidence which indicates the makers must have been Neanderthals.

The cave is located on a 100 m high plateau in the Touraine Region, which is covered by crop-fields and woodland, and made up of Cretaceous marine sedimentary rock. The Loire Valley cuts through the plateau, to a depth of about 50 m, with the La Roche-Cotard site on the northern side of this valley. The cave, LRC I, is cut into Upper Turonian (Late Cretaceous) soft, sometimes crumbly, sandy yellow limestone. The top of the plateau is covered by a thin layer of silty sand, about a metre thick, which accumulated as a wind-blown deposit during the last glacial. The bedrock is not generally visible on the sides of the plateau, except where it has been exposed by Human activity, having been covered over by solifluction or runoff. The cave appears to have been repeatedly flooded by the River Loire, which is also likely to have been at least partially responsible for its dissolution. While in the Holocene, all of the La Roche-Cotard sites were covered by sediments until these were removed by Human activities in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in the Late Pleistocene the River Loire was closer to the base of the slope, and would have rapidly removed such sediments, keeping the area accessible to both Animal and Human inhabitants of the region. During the early Holocene, the river shifted its course to the other side of the valley, and sediment began to accumulate, covering the area until much of it was removed in the 1840s to use as building materials for the construction of the Loire Valley Railway.

The La Roche-Cotard Cav is about 33 m deep, running southeast-to-northwest, with four main chambers; the Mousterian Gallery, the Lemmings Chamber, the Pillar Chamber and the Hyena Chamber. It may have extended further back in the past; the rear of the Hyena Chamber having collapsed at some point. The soft rock from which the cave is made also contains large slabs and knobs of harder, silicified sediment, which appear to have lent some structural strength; the ceiling of the cave is a silicified layer (the Langeais Hardground), which marks the base of the e Coniacian Epoch.

The cave opens into the Mousterian Gallery, which has a quartzite sandstone floor, 49.2 m above the Nivellement Général de la France (general levelling of France), and a ceiling 51 m above the same, made from silicified biocalcarenite. at the west end of this chamber a passage 2 m high and 1.5 m wide leads to the Lemmings Chamber. This has two small openings to the outside on its eastern side, and a large passage leading to the Pillar Chamber at its northwest. This chamber has a large central pillar, and a large quartzite slab which forms an extensive platform several tens of centimetres above the floor of the chamber. This has been broken at the north end of the chamber, though a section is still attached to the north wall; this part of the chamber still contains a considerable amount of sediment. The Hyena Chamber can be reached from the Pillar Chamber via a narrow, sinuous passage.

Methodical exploration of the La Roche-Cotard sites began in 2008. Remains attributed of large, medium, and small Vertebrates were uncovered on several levels, and studied systematically, although a palynological analysis was not possible, as the environment comprised porous sediments through which well-oxygenated water had been able to percolate. The location of any lithic remains and faunal remains greater than 2 cm were carefully mapped; sediment samples were then sieved for smaller faunal remains.

Most of the sediment from the LRC I cave was removed in 2012, but sufficient was left within the Pillar Chamber to establish a stratigraphic sequence, with a sandy layer with soft reddish clay pebbles filling a small natural funnel formed in the tuff by water at the base, over which was a compact clay layer with tuff gravel, bone fragments, coprolites, and then two modern, disturbed layers, although none of these can be correlated to any sedimentary unit identified elsewhere. The area in front of the cave entrance produced a very sandy Lower Layer, overlain by a Middle Layer consisting primarily of silt from overflowing of the Loire, and an Upper Layer formed of gelifracts (sloping beds leaning against a rock face) and aeolian sand.

Outside of the cave, five sedimentary units were found across the area. The lowest layer is mainly composed of tuff blocks separated by voids filled with sandy reddish clay, with areas of brown to greenish-yellow, fine silty sand with largely subordinate clay; this layer is thought to be largely derived from weathering of the underlying rocks. The layer above this consists of sandy to silty brown to greyish layers, which are only slightly or not at all carbonated, thought to have been laid down as bottom deposits within the River Loire, at a time when its meandering covered the sites. The third layer consists of a light brown carbonated matrix, with abundant frost-fractured quarzitic sandstone slabs and a few sandy blocks, thought to be a mixture of material that has moved downslope in a landslip. The penultimate layer is brown and texturally selected. It is made up of slightly carbonated fine-grained sand and silt, and its upper limit is tilted toward the south; this layer is thought to comprise aeolian material blown in during a Pleistocene dry phase. Finally, the uppermost layer, which presumably extended everywhere on the slope before 1846, consists of brown to greyish, very heterometric sedimentary layers composed of a dominant silty sand matrix with variable abundance of flint and limestone fragments, thought to be the result of Holocene soil formation, with perioding inclusions of runoff material from the slopes above.

Much of the sediment that filled the cave was removed by François d’Achon in 1912, but sufficient remained for Marquet et al. to develop a stratigraphy for the cave interior. The conduit connecting the Lemmings Chamber to the exterior still contains an undisturbed sequence, comprising two layers, the lower of which Marquet et al. equate to the river sediment layer found outside the cave, and the upper the landslip material which overlies this. In the main cave entrance two niches are again filled with river sediment, while in front of the entrance more of this sediment is covered by a large block of fallen limestone. Some smaller tunnels above the cave were found to be filled with the soil which forms the uppermost layer elsewhere, and a trench excavated above the cave entrance found the same, while a cave excavated below the entrance found a more complete stratigraphic sequence.

Lithostratigraphy and geometric distribution of the superficial deposits outside the cave. (A). Block diagram with loci

positions and in particular the sub-loci LRC I-a to d. The stratigraphy of the layers intersected by LRC II (B), LRC III (C) and

LRC IV (D). For each locus, the stratigraphic units (U5/red, U4/blue, U3/brown, U2/orange, U1/green) and their vertical

extension is indicated. Each unit comprises several layers. Marquet et al. (2023).

Lithostratigraphy and geometric distribution of the superficial deposits outside the cave. (A). Block diagram with loci

positions and in particular the sub-loci LRC I-a to d. The stratigraphy of the layers intersected by LRC II (B), LRC III (C) and

LRC IV (D). For each locus, the stratigraphic units (U5/red, U4/blue, U3/brown, U2/orange, U1/green) and their vertical

extension is indicated. Each unit comprises several layers. Marquet et al. (2023).Based upon this, Marquet et al. conclude that, at some point after the cave was formed, it was entered by the river, which filled it to a height of at least 60 cm. Some time after the waters receded, the entrance the entrance of the cave was sealed by a landslip, with subsequent Pleistocene and Holocene sedimentary layers forming over this, probably forming a layer about 10 m thick before quarrying began in the 1840s.

François d’Achon's 1912 excavations recovered a considerable amount of large- and medium-sized Animal remains within the cave, but their locations were not recorded. The more recent excavations also found significant amounts of such remains, principally at the LRC III and LRC IV sites, the locations and stratigraphic placement of which were carefully recorded. Some of the bones from all four locations show signs of Human activity, including cut marks, burning, and modification for use as tools. Most of the remains appear to have come from Animals that would have occupied the area during temperate phases, such as Bison and Aurochs, Equids and Red Deer. A sequence of predators could also be established, with the area first being used by Cave Lions and Bears, then by Humans, and lastly by Hyenas. In some places an upper faunal layer, comprising cold-period species, such as Marmot and Reindeer, was present. Remains of smaller Vertebrates, including Mammals, Fish, Amphibians, Birds, and Reptiles, were recovered by sieving sediments.

All four sites also produced Human-manufactured tools. All of these belonged to the Mousterian lithic assemblage, with no later material found. François d’Achon uncovered two assemblages of lithic artefacts within the cave LRC I, although all of these have subsequently been lost, with only a single photograph and some drawings surviving to the present day. The tools are made from Lower Turonian flint, which is available in the form of pebbles in the river terraces. The items documented include a number of Mousterian bifaces in the top part of the lower layer in a corner of the Pillar Chamber, and debetage (flakes) apparently produced using a Levallois technique (the progressive removal of flakes from a prepared core by striking with a percussive tool), within upper part of the lower layer close to the cave entrance, beneath a stone structure which d’Achon believed was a fireplace. Marquet et al. uncovered another Mousterian biface in the South Pillar Chamber, d in the remnants of an unidentified layer. They also found some thin elongated flakes in the lower layer of the Mousterian, at a depth below that to which d’Achon had excavated. Another blade was found on the top of the lower layer within the Pillar Chamber, though this is difficult to place stratigraphically.

Levallois flakes were also found at the LRC II site, in the same layer as the 'Mask of La Roche-Cotard', at the LRC III site, below a layer of faunal remains apparently gnawed by Hyenas, which in turn was below a layer with the remains of Arctic Lemmings, and Narrow-headed Voles (both Arctic-adapted Rodents), neither of which layers produced any tools. At LRC IV, more Levallois flakes were found associated with the bones of cool temperate large Mammal remains, and overlain by a layer containing the remains of Arctic Lemmings, but no tools.

Thus all of the lithic items which can be placed within a stratigraphic context (i.e. everything but the items from the Pillar Chamber, clearly comes from the same deposit, which records a warm period followed by a glaciation, and all of the items belong to the Moustrian technology, which is clearly associated with Neanderthals in Europe. None of these items show any sign of having been transported by water.

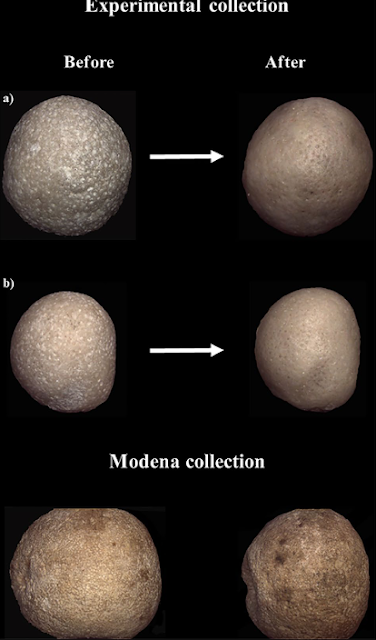

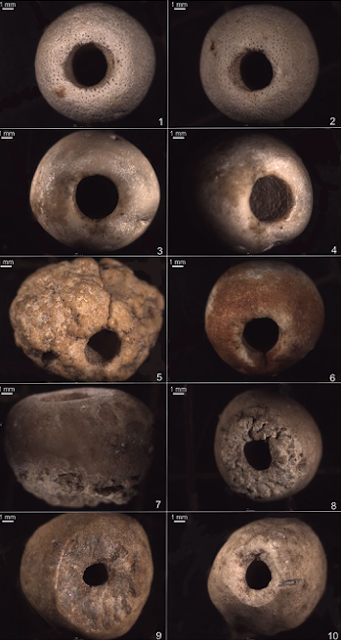

A variety of markings are present on the walls of the La Roche-Cotard Cave. Some of these marks are clearly the result of Human activity, but others can be attributed to Animals, such as Bears or Badgers, or chemical processes, such as surface dissolution, disintegration, dehydration, and concretion formation. Markings made by the claws of Animals typically have a characteristic spacing and incision angle, depending on the type of Animal involved, whereas Human markings are much more variable, and include spatially organized elongated marks and patterns of dots unlike anything any Animal will make. Such marks are found on a 13 m-long section of the northeast wall of the Pillar Chamber. The marks are aranged in distinct geometric patterns, which are grouped together to make a series of distinct panels linked by groups of smaller marks. A linear discrimination analysis of the width, incision angle and depth of 116 marks revealed two statistically distinct groups: 32 with features consistent with claw marks, while the remaining 84 appeared to be of Human origin. This was based upon the assumption that Animal claws will make shallow marks with a v-shaped profile, while a finger or finger-shaped tool with make deeper, often u-shaped marks (this was confirmed experimentally on a section of similar tuffaceous limestone intentionally uncovered close to the cave). The Human-made markings were aranged in eight separate panels, apparently reflecting two separate aproches to art-making,, with the six panels being similar, and probably made with fingers, while the two were distinct, and apparently made with a tool, although it was not possible to identify the type of tool used.

All of the panels are found on a section of wall showing a thin layer of chemically altered material, above a horizontal overhang attributed to the pooling of water (which would have eroded the cave wall at the base). Below the overhang the wall has numerous niches attributed to dissolution, but no signs of any intentional markings. The altered surface has two layers, the outer of which comprises grains of sand and fragments of shell in a clay matrix, while to inner is very similar to the underlying tuffaceous limestone. This coating is missing in many places, having apparently been rubbed off by the actions of Animals or eroded away by dripping water.

The first six panels (panels a-f) appear to have been made with fingers alone, and have an average height 1.5-1.7 m above the presumed level of the floor at the time when they were made. Most of the finger markings are thought to have been made with a finger laid flat, but some seem to have been made with the side of a finger. The seventh panel (panel g) is at a height of 1.8 m, placing it just below the ceiling of the cave; the wall here does not have an altered covering, while the limestone matrix is rich in quartz and fossil fragments. The eighth panel (panel h) is only a metre high, and comprises a series of puncture marks apparently made with a tool.

The nature of the wall-coating, with a thin, easily-removed layer over a more resilient surface, has a major impact on the form of the finger markings, which are quite different from similar markings made on a clay surface; it would have been easy for the mark-makers to remove the surface layer, exposing the underlying matrix, which would have given the images a smooth appearance when they were made, with the markings having clear, well-defined boundaries, which have since been blurred by the processes of water condensation, drip erosion, and even air circulation.

The closest panel to the entrance, known as the Entrance Panel, or panel a, comprises a set of 36 finger traces made on a flat panel measuring roughly 50 cm by 50 cm. These traces run from top right to bottom left, and are roughly parallel, varying in length from 5 cm to just under 10 cm, and being about 1.5 cm wide. The marks are well defined at the top of the panel, becoming fainter towards the bottom. Some Animal scratches are present on the right part of the panel. The alteration layer is thin on the wall surrounding this panel, possibly due to its position close to the chamber entrance.

The next panel in, known as the Fossil Panel, or panel b, is about 80 cm long, and has a set of eight well defined finger traces above, and 21 fainter finger traces below. All of these traces are aligned obliquely, sloping either to the right or the left. There are also a large number of circular or nearly circular puncture marks, arranged in three groups, 19 on the right, six on the left, and twelve associated with a large Bivalve fossil, Bimorphoceramus turonensis. Another, isolated, elongate finger mark is associated with this fossil. A single Animal mark, made by four claws, is present on this panel. The whole panel appears to have been constructed around the Bivalve fossil.

The third panel, known as the Linear Panel, or panel c, is 150 cm long and only 50 cm high. The top right side of this panel has a motif of four finger traces descending to the left at 45°, while below and to the left of this an apparent continuation has the same motif but the marks of only three fingers, and below and to the left of that, another continuation also has only three finger-marks. Each of these motifs is about 20 cm in length. At the top, and to the right, of these markings are a group of 13 puncture marks. On the left hand side of the panel are 34 lines, most of which are horizontal and arranged into groups. The uppermost three of these are about 40 cm in length, the rest 10-15 cm, There are very few puncture marks on this part of the panel, but in the bottom left hand corner are four v-shaped marks.

The next panel is identified as the Undulating Panel, or panel d. This panel is 70 cm long and 50 cm high, and largely covered by 84 linear finger traces, from 10 cm to 33 cm in length. Shorter lines are typically grouped together, and sometimes associated with dots. A few isolated dots can also be found. Three of the longer lines appear to run from left to right, and have a double undulation. Above and to the left of these are two subparallel traces, one of these starts at its highest point, the other is harder to delineate as it appears to widen. Next to these are two groups of finger traces, apparently orientated towards a wavy line. Two further long lines appear to give a boundary to this structure. This panel seems to be more intentionally composed than the earlier panels.

The next panel is known as the Circular Panel, or panel e, and is 50 cm wide and 60 cm high. It comprises two separate sets of marks, on the left a set of seventeen finger tracings and on the right a set of 31 dots. The lines predominantly run from top to bottom, but curve outwards around a central empty spane, clearly forming a deliberate pattern. A set of outer markings may relate to this, while underneath is another long horizontal line, with two closely associated short vertical lines. This panel is very close to the Undulating Panel, and the two may have been intended to form a single entity.

The next panel is known as the Triangular Panel, or panel f, and is 60 cm wide by 50 cm tall. This panel has 25 parallel finger flutings running from top to bottom, and parallel to one another. ranging from 8 cm to 32 cm in length, with the longest at the right side of the panel. The panel forms an inverted isosceles triangle, with its base at the top, and is located above the entrance of a large, regular alcove. The main vertex of this triangle is emphasised by a piece of chert embedded in the wall at its lowest point.

The seventh panel, known as the Rectangular Panel, or panel g, is 30 cm long and 25 cm high, and covered by 22 elongate traces made with a flat tool or the side of a finger, giving them a v-shaped profile, and seven elongate traces mage with the flat of a finger, giving them a u-shaped profile. All of these traces are between 6 cm and 20 cm in length, and all are verticle and sub-parallel, giving the whole a slight fan-shape.

The final panel, identified as the Dotted Panel, or panel h, and is a metre long and 60 cm high, and has 110 dot-shaped traces, mostly 12-15 mm in diameter, although some are more oval, reaching 20-25 cm in length, or elongated, up to 8 cm. In addition there are a series of oblique lines 3-12 cm in length in the lower part of the panel. There are also a series of marks apparently made with a metal tool, probably during the original excavation of the cave in 1912, as well as a large number of Animal traces; both of these might have destroyed other traces on this panel.

The La Roche-Cotard Cave and associated area was once clearly occupied by a group of Humans, who have left lithic artefacts of a Moustrian technology at all sites, within a coeval sedimentary deposit. There are no further signs of Human occupation until the nineteenth century. There are also engravings on the walls of the Pillar Chamber of the cave, which seem likely to have been made by the same people, although there is no direct evidence to support this.

Marquet et al. set about dating these carvings using optically stimulated luminescence dating, which can reveal the date at which a sample was last exposed to light; this potentially gives the date when an object is buried, but can be reset if an object is subsequently exposed, making it unreliable on its own, but providing a plausible test for radiometric dating results. At La Roche-Cotard it was possible to target sediments inside the cave entrance, in two niches in the cave entrance and around the cave entrance, as well as two complete stratigraphic sequences at sites LRC I-II and LRC IV, in order to try to estimate when the cave was sealed. In addition radiocarbon dating was carried out on nineteen bone fragments collected from all four sites.

Some of the bone samples yielded 'non-finite' radiocarbon dates, which essentially means that they are older than 45 000 years old, and outside the range of carbon dating, while the remainder produced dates clustered around 40 000 years ago; such dates are also regarded with caution, as this is at the limit of the techniques range, where dates are often unreliable; such results are quite often returned for material which is considerably older. Due to this, Marquet et al. did not use these dates in their reconstructed timeline for the habitation of the area, relying entirely on optically stimulated luminescence dating.

The sediments at La Roche-Cotard show signs of having been well-bleached by sunlight before their burial, making them particularly suitable for optically stimulated luminescence dating. The sedimentary unit within which all the tools which could be placed within a sequence (i.e. all the tools except those from the Pillar Chamber) were found was dated to between about 99 000 and about 45 000 years old. Within the cave (LRC I), the tools were covered by a sediment layer which could be dated to between 68 400 and 63 200 years old, while the layer containing the tools at the nearby LRC II is dated to 97 500 years ago, and the layers above this produced dates of 95 600 and 88 500 years before the present. At LRC III, the tools were found within the base of a layer dated to about 65 000 years ago, whilt the LRC IV tools are covered by a layer dated to 79 400 years before the present.

The sediments of the Loire Valley at La Roche-Cotard include intercalated fluvial deposits and landslip gelifracts, dating from between Marine Isotope Stage 5c (roughly 96 000-87 000 years ago) and Marine Isotope Stage 5a (roughly 82 000-71 000 years ago), which probably represent the alternating stadials (cold periods, when the water would have been low) and interstadials (warm periods, when the water would have been high). Only a small number of stone tools found implies that this site was only intermittently occupied by the toolmakers over this period. This probably reflects the fluctuating climate, and limited amount of workable stone in the area.

The chronology of the La Roche-Cotard Cave (LRC I) over this period is not well understood, but Marquet et al. were able to directly date the layer of river silt which had been deposited within the cave, overlying Moustrian tools. This flooding is calculated to have begun about 70 000 years ago, presumably ending any Human occupation of the cave. The sediment partially blocked the entrance to the cave, leaving an entrance only about 70 cm high (inconvenient, but not impossible for a Human to enter), but did not reach the bottom of the engravings on the cave wall, leaving the possibility that they could have been made after the waters receided, by members of a much later Human population. No tools were found on top of the silt layer, making it unlikely that it was occupied by Humans post-flood, but bones of large Mammals with marks indicating predation by Hyenas were, suggesting that the cave did remain open.

The cave appears to have finally been sealed by a combination of wind-blown sediments and a landslip during the Last Glacial interval. with complete closure achieved by 51 000 years ago. Modern Humans are not known in Western Europe before 45 000 years ago, which means that any engraving left in a cave in Western Europe before 51 000 years ago must have been left their by a Neanderthal artist.

The artwork is organised onto a set of discrete panels, on the longest wall of the cave complex, excluding the entrance way. The first six of these panels appear to show a form of progression, with the images becoming more complex and organised deeper into the cave, with the complexity of the patterns apparently showing a degree of planning and intent, something which implies a complex thought process. However, the designs are entirely abstract, with no direct figurative images, something La Roche-Cotard has in common with other Neanderthal sites in Europe and the Middle East, and indeed Modern Human sites in Africa. The abstract nature of this art makes it impossible to tell if it has a symbolic meaning, but it does add to a growing body of knowledge about the capabilities of Neanderthals for artistic expression.

See also...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Twitter.