The appearance of symbolic thinking is considered to be one of the most important steps in the development of modern Human cognition, giving Humans the ability to pass on information by means of objects rather than direct communication, and thereby helping to build communities bound by common cultural traits rather than simple kinship. Evidence of this, however, is difficult to detect in the archaeological record, leading to intense debates as to when and where such behaviour first appeared.

The first shell beads appear over a hundred thousand years ago in Africa and the near east, at sites such as Skhul Cave in Israel, where beads have been dated to 135-100 000 years before the present, Qafzeh Cave, also in Israel, dated to 100-92 000 years ago, Blombos Cave in South Africa, 100-70 000 years ago, Sibudu Cave in South Africa, older than 70 000 to about 60 000 years ago, Border Cave, again in South Africa, 125-35 000 years ago, Grotte des Pigeons in Morocco, 80 000 years ago, Bizmoune Cave in Morocco, at least 142 000 years old, Rhafas Cave, also in Morocco, 82 000 years ago, Contrabandiers Cave, once again in Morocco, 120-90 000 years ago, and Oued Djebbana in Algeria, 100-90 000 years ago. All of these sites are associated with early anatomically modern Humans, apparently confirming that beads were an innovation novel to this group. It has been suggested that symbolic thinking appeared in anatomically modern Humans, providing them with a cultural edge that enabled them to replace all other Hominins. However, recent evidence has suggested that some other Hominin species also used symbolism, which would indicate a far earlier origin within the genus Homo. This analysis has largely revolved around the use of personal ornaments, such as beads, pendants, bracelets and diadems, which are taken as evidence of symbolic thought.

One group particularly associated with bead-making are Neanderthals, something which ties into deeper questions about this group's abilities, and relationship to modern Humans.

Neanderthals were for a long time (and often still are) classified as a separate Hominin species, Homo neanderthalensis, possibly the most advanced Human species other than ourselves, but nevertheless separate and inferior. However, more recent genetic studies have shown that many modern Humans, and probably all non-African Humans, carry some Neanderthal DNA, which challenges this view of separateness.

This has led to differing views on the taxonomic status of Neanderthals; possibly they were still a separate species, Homo neandethalensis, but only recently diverged and still capable of interbreeding with us (which is tricky, because in biology populations are generally defined as different species when they are incapable of interbreeding). Alternatively, maybe they should be seen as a modern Humans, but belonging to a different subspecies, Homo sapiens neandethalensis (with all living Humans being classified as Homo sapiens sapiens), which acknowledges that they were different from us, but not that different. Finally, maybe they should be seen as completely modern Humans, but belonging to an ethnic group which has disappeared; making them no more different from living Humans than modern Europeans are from modern Africans.

Much of this debate revolves around the cognitive abilities of Neanderthals. As a group, Neanderthals are strongly associated with the Acheulean Palaeolithic technology. This technology first appeared in Africa about 1.76 million years ago (long before the appearance of Neanderthals), and spread across much of Africa and Eurasia, being used by a variety of Hominin groups. Neanderthals first appeared somewhere between 800 000 and 315 000 years ago, and used Acheulen technology throughout almost all of their history, although some later groups appear to have adopted different technologies learned from Modern Human neighbours. Thus, while Neaderthals are strongly associated with the Acheulean technology, particularly in Europe, not all Acheuleans were Neanderthals, and not all Neanderthals were Acheuleans.

This long use of a single tool-making technology, apparently without any innovation, has been used to suggest that Neanderthals lacked the capacity for abstract imaginative thought; they were capable of copying what they had seen others make, but were quite incapable of coming up with new ideas for themselves. However, despite this apparent lack of innovation in tool-making, Neanderthals are also thought to have been capable of considerable artistic output, with material attributed to their output including pendants made from the claws of Birds of Prey, a bone flute, cave paintings, and numerous beads, some made from shells, but many of them made from fossils of the Cretaceous Sponge, Porosphaera globularis.

In a paper published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences on 1 August 2022, Gabriele Luigi Francesco Berruti of the University of Ferrara, and of the Association 'P-Project Prehistory Piedmont', Dario Sigari, also of the University of Ferrara, and of the Geoscience Center of Coimbra University and the Archaeological Cooperative Society, Cristiana Zanasi of the Civic Museum of Modena, Stefano Bertola and Allison Ceresa, again of the University of Ferrara, and Marta Arzarello, once again of the University of Ferrara, and the Association 'P-Project Prehistory Piedmont', assess the authenticity of the Porosphaera globularis beads, and assess whether they were genuinely made by our Neanderthal forebears.

Berruti et al.'s study concentrates on a collection of Porosphaera beads in the collection of the Civic Museums of Modena, which were obtained in 1891 from the French police commissioner and antiquarian Charles Le Beuf, who collected them from Saint-Acheul in the Somme, the type locality for the Acheulian culture (i.e. the site from which that culture was named, and to which material from other locations is compared when deciding if it can be classified as 'Acheulian'.

Porosphaera beads were collected from Acheulian sites across northwest France and Southern England in the nineteenth century. They are clearly made from fossils of the Cretaceous calcareous Sponge Porosphaera globularis, which was naturally rounded, but have holes bored through them, which nineteenth century archaeologists interpreted as evidence of their use as beads. The problems with this are that the Sponge fossils are found in the same chalk layers that Acheuleans (and later people) excavated for flints from which to make tools (meaning that Acheuleans would have been digging them out whether they subsequently used them or not), and that about 9% of these fossils have 'natural' boreholes in them, made by Cretaceous Sipunculid Worms.

Thus there could be three possible explanations for the 'beads' found by nineteenth century archaeologists. Firstly, they could be exactly what they were assumed to be; beads made by Acheuleans as personal ornamentation. Secondly, they could be Sponges with boreholes made by Cretaceous Worms, which were then collected and used as beads by the Acheuleans. Finally, it is possible that these Sponges were bored by Cretaceous Worms and overlooked by the Acheuleans, but collected by nineteenth century archaeologists, who had preconceived ideas about what beads looked like which the Acheuleans lacked.

Whereas a modern site used as the type for an archaeological culture (or palaeontological species) would be recorded very precisely. The Saint Acheul 'site' actually refers to an entire region in the suburbs of Amiens, with several different locations producing material, some of them from several different layers. The earliest of these contains material dated to 670-650 000 years before the present, and marks the earliest spread of the Acheulian culture into northern Europe. Accurate recording of the level from which the Porosphaera beads were obtained is lacking, but it is thought that they came from the same layers as flint tools recorded from the site.

In 1891 the then director of the Civic Museum of Modena, Carlo Boni, purchased a collection of beads and stone tools from Le Beuf for 400 Francs. The Porosphaera beads were assembled by Boni into four necklaces, three using raffia threads and one using metal wire, with each necklace having between 112 and 156 individual beads. These were then mounted on a cardboard panel for display purposes, using some red ribbon. The beads have remained on this mount to this day, with both the beads and the panel having gained a coating of dust and an organic crust derived from the breakdown of the cardboard.

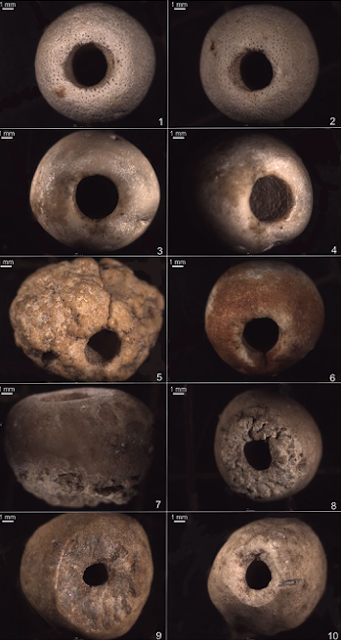

Berruti et al. disassembled Boni's necklaces, in order to obtain a specimen of 520 beads, which were then individually examined. The perforations in these beads were found to be larger than the 'natural' holes caused by Cretaceous Worm-borings, and the beads themselves were, on average more uniform in size and more rounded than a selection of random Porosphaera globularis fossils. This implies strongly that the beads in the Moderna collection have been subjected to Human selection, although whether this was by Acheuleans or nineteenth century archaeologists is unclear.

Next Berruti et al. examined wear traces on the beads, finding that they showed wear around their perforations (as would be caused by a string, whether ancient of modern), and on the surfaces where the perforations were found (i.e. on the surfaces where the beads would rub-together while suspended on a string), but not on other surfaces of the beads. Furthermore, many of the beads had developed a patina, which was not seen on the surfaces adjacent to the holes. All of these have been recorded on Porosphaera beads used in other studies, and taken as evidence of the beads having been worn on a string of some description, and having rubbed against one-another while being worn.

However, Berruti et al. consider that while these traces could have been made by the actions of fashion-conscious Acheuleans, it is also possible that they could have been caused by the actions of nineteenth century antiquarians, either intentionally, to increase the value of their finds, or inadvertently, while mounting the beads onto strings for display purposes.

Since this matter cannot be resolved by looking at wear on the beads caused by them rubbing against one-another on a string, or the friction of the string itself, Berruti et al. consider an alternative source of information, namely to what extent would the beads by modified by rubbing against the skin of their wearers? (Clothing has never been found in association with Acheulean archaeological sites, and these people are therefore assumed not to have worn clothing). If the beads had never been worn by Acheuleans, but rather collected and strung by antiquarians for the first time, then any markings left by such rubbing against skin should be absent.

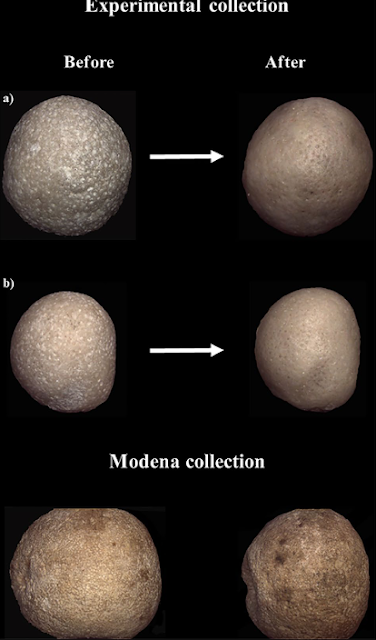

To this end Berruti et al. obtained five non-perforated specimens of Porosphaera globularis (which, lacking perforations, could never have been worn as beads), and tested these by rubbing them against Pig skin (considered similar enough to Human skin to be used in a variety of trials) for a total of ten minutes each; three of the beads were rubbed against clean skin and two against dirty skin.

All of the beads showed signs of abrasion and rounding after ten minutes, suggesting that they would be unlikely to survive long-term wear as items of jewellery work against the skin. The beads rubbed against dirty skin developed distinctive striations within the ten minutes, a phenomenon absent in the Moderna beads.

Close examination of the Moderna beads enabled them to be divided into three groups, based upon their geology. The first of these show signs of having been rolled on the seafloor before being buried, producing a unique set of scratches and markings. The second group have been partially or wholly remineralized after being buried. The third set show no signs of either mechanical abrasion or remineralization.

Berruti et al. looked for signs of intentional modification of the wholes through the beads, from which it might be possible to determine the nature of the tool being used, and therefore whether the person carrying out this action lived in the Palaeolithic or the nineteenth century. Several of the beads show signs of mechanical action around the hole, though it cannot safely be said whether this was a result of drilling by bead-maker, or abrasion by the string. In two cases the hole through the bead was hourglass shaped, which was most likely caused by drilling from each end, but is was not possible to tell what tool was used, not when this action occurred.

In the late nineteenth century the concept of symbolic thought, and its importance as a step in the development of achieving the cognitive abilities of modern Humans, was barely (if at all) understood. Even today, there are those who believe that this is a unique trait in anatomically modern Humans, and that any evidence for this in Europe prior to the arrival of anatomically modern Humans, about 40 000 years ago, must be erroneous. Many scholars in the field, however, support the idea that this, like other traits, must have evolved gradually, and therefore it is not unreasonable to expect to find evidence for some sort of symbolic thought in earlier groups.

The apparent use of personal ornamentation by Neanderthals has been seen as a clear piece of evidence in support of this idea, and the presence of beads in the classical Acheulean deposits as fairly strong evidence of the creative abilities of Neanderthals. However, the Saint Acheul beds are significantly older than any other deposits thought to have yielded material associated with personal ornamentation (made by Neanderthals, anatomically modern Humans, or anybody else), which should automatically raise questions about the reliability of these items.

Based upon this analysis, Berruti et al. conclude that the Acheulean Porosphaera beads are entirely natural in their origin; possibly with a little bit of help by over-enthusiastic nineteenth century antiquarians, but definitely not produced by early Acheuleans.

Berruti et al. do not, however, extrapolate from this data to assume that all evidence of symbolic thought attributed to Neanderthals are false. There is a considerable body of evidence which suggests that Neandethals were capable of artistic representation, albeit later in their history than the Saint Acheul deposits. Even if this evidence is all erroneous, and our current ideas about Neanderthals are completely wrong, this will only be overturned by looking at the validity of each individual piece of evidence, with no single source of data being able to tell the whole story.

See also...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Twitter.