Reworked Late Ordovician Sponges have been collected from Miocene to

Pleistocene across a wide area of northern Europe for over two centuries. These

are associated with the course of the Baltic River System, which drained much

of northern Europe for much of this time period. There are four main

assemblages of such fossils recognised. The German-Dutch Sponge Assemblages are

collected from the border area between Germany and the Netherlands, and were

deposited on the Baltic River Delta in the Early Pleistocene. The material here

is found in brown silicified limestones and chert (these are common materials

in fossil assemblages rich in Sponges, as the silica spicules of the Sponge

dissolve, then precipitate out with chemical changes in the buried sediments,

replacing other materials), and is referred to as the Brown Sponge Assemblage.

The deposits around Lausitz, to the southeast of Berlin, were deposited in the

Middle Miocene, and comprise largely bluish-grey or black silicified material,

known as the Lavendel Blaue Hornsteine. The Island of Sylt in northwestern

Germany produces reworked material laid down in the Pliocene; this is dominated

by material from the Lavendel Blaue Hornsteine, with a small amount of Brown

Sponge Assemblage material. The Brown Sponge Assemblage is also found on the

Swedish island of Gotland, in the Baltic, where a wide variety of Sponges have

been recognised.

In a paper published in the journal Scripta Geologica in March 2014, Freek Rhebergen

of Emmen in the Netherlands describes a new species of Anthaspidellid Demosponge

from reworked Ordovician material from Gotland, the Dutch-German border region

and the Island of Sylt.

The new species is named Brevaspidella dispersa,

where ‘Brevaspidella’ means

‘little-short-shield’, in reference to the shape of the Sponge, short and

cylindrical with a shield-like top, and ‘dispersa’

means ‘disperse’ a reference to the scattered osculi (exhalent openings) on its

surface (Sponges are filter feeders that pump water in through tiny

canal-openings all over their surface, and out through one or more larger

openings known as ‘osculi’). The species is described from specimens from the

Museum of Gotland, the Swedish Museum of Natural History, the

Archiv für Geschiebekunde in the Geologisch-Paläontologisches Institut und Museum

of the University of Hamburg and several private collections.

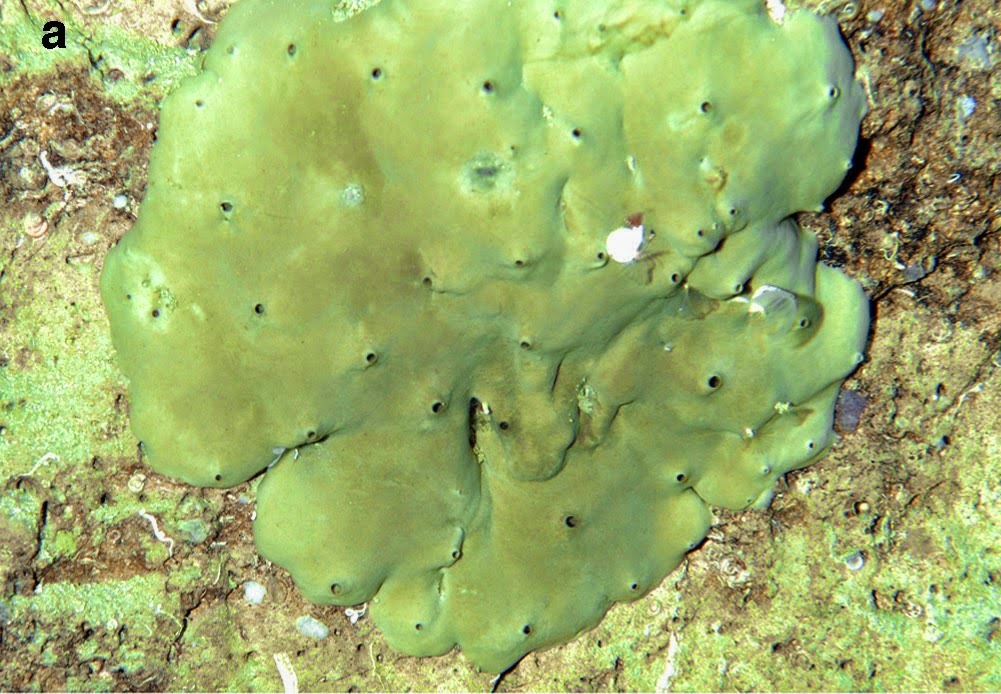

Specimen of Brevaspidella dispersa from

unknown locality on Gotland, Sweden. Flat to slightly concave upper surface

with cluster of osculi and some converging lateral canals. Rhebergen (2014).

Brevaspidella dispersa is a small Sponge, typically less than 5 cm across, with the height

and diameter about the same. The upper surface is slightly concave with

scattered osculi, the base flat or slightly concave with a thickened dermal

layer with concentric wrinkles.

Brevaspidella dispersa. (A, B) Specimen from beach near Västlanda, Gotland, Sweden. (A)

View on upperside with dispersed osculi and radial surface canals. (B) Lateral

view with concentrically wrinkled dermallayer in the lower part. (D, E) Specimen

from unknown locality on Gotland, Sweden. (D) The top shows morethan 50 osculi,

scattered over the flat surface. (E) Side view. Dermal layer poorly developed

and restrictedto the base. Rhebergen (2014).

See also…

The shallow water reefs around Bonaire and Klein Curaçao in the

Caribbean Netherlands are well studied and are considered a biodiversity

hotspot, but the...

Sponges

(Porifera) are generally considered to be the oldest extant animal group, with

a fossil record that extends considerably into the Precambrian; phylogenomic

analysis suggests they are the sister group to all other animals, which also

suggests an early origin for the group.

Chalinid Dermosponges are among the hardest Sponges to classify

taxonomically due to their simple anatomies and variable morphologies.

They are encrusting Sponges with skeletons made up of...

Follow Sciency Thoughts on Facebook.